A day to consider the creative side of social justice

How would our country be different if we acted as if culture were a human right and everyone could participate?

Culture is a human right and everyone has the right to participate. — U.S. Department of Arts and Culture

The top official of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture was in Kalamazoo recently on a fact-finding mission. If you just thought, “Wait. The U.S. doesn’t have a Department of Arts and Culture” — you could be forgiven for thinking that.

There is no such agency in the federal government, nothing at the cabinet level. But it does exist because the people took the matter into their own hands and created it.

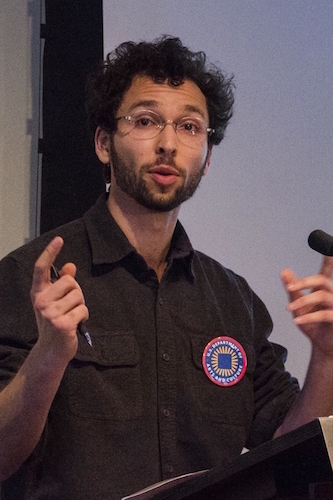

“We made it up,” says Adam Horowitz, the self-styled Chief Instigator of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture.

Horowitz — a man who signs his email “Yours in cahoots, Adam” — was in Kalamazoo at the invitation of the Transformations Spirituality Center as part of a day called “Imagining Justice In Your Community.”

For participants, it was quickly obvious this was not just another meeting. As they arrived they had been asked to give themselves titles. (A late riser, I chose Chief Sleepyhead.) Then Horowitz opened the day with a statement acknowledging the group was gathered on the traditional land of the Potawatomi, stewards of the land for generations. U.S.D.A.C. encourages people to open all public events and gatherings with reverence and respect by including a statement recognizing the area’s Native peoples.

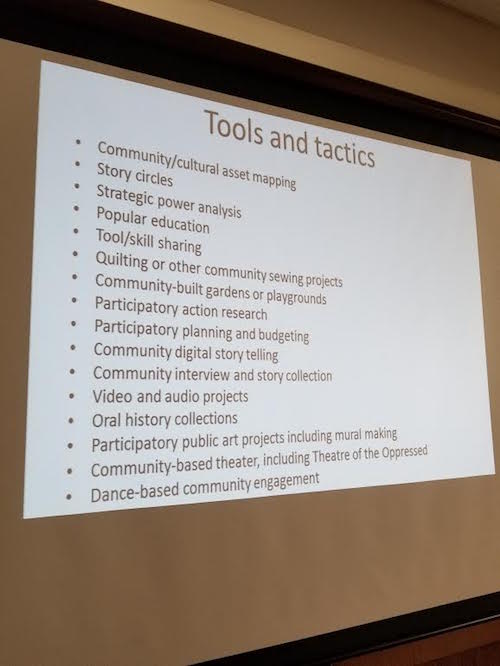

In a day sprinkled with poetry, song and inspired quotations, a flow of collaborative ideas emerges, as Horowitz leads a roomful of activists, advocates and artists through a series of activities designed to identify creative projects in the community that people could support.

Who is here? A group of students from the Wesley Center on the Western Michigan University Campus, Eastside neighborhood residents, leaders of various local organizations such as Building Blocks, a pastor leading a Spanish speaking men’s group, and those from beyond Kalamazoo. And, of course, some of the Sisters of St. Joseph.

Horowitz introduces the idea of story circles, where listening is as important as speaking and no questions are asked until everyone has spoken. “We all take up the same amount of space,” Horowitz says.

From story circles can come deep connections, he says. They can show us our shared values and help build a sense of community. Meaning making comes as people reflect on the stories told. “Something that breaks our heart makes us do something different,” he says.

After lunch, the creativity gets turned up. The gathering divides up into smaller groupings, each of which identifies challenges that a community art or cultural project could address. Then they identify cultural assets that would help address those challenges — the space, talents, traditions, demographics, and rituals that could go into the project.

A contingent from the Eastside proposes turning an unused firehouse into a focus for the neighborhood, a place for children’s programs, a food pantry, the starting point for bike trails, a drop-in art studio, and a spot where small businesses could get a start.

Another group suggests the Kalamazoo Dreamer’s Conference, where those working to make the community a better place could get to know one another and build collaborations. A third group calls for a Festival of Festivals, where each of the community’s cultural festival could be represented. And a group from Hastings comes up with plans for a collaboration that will lead to an incubator.

Horowitz says the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture’s local organizing helps communities dream aloud and turn their dreams into reality. It also takes the language of mainstream politics and has fun with it, for example, Super PACS become Participatory Arts Coalitions. The State of the Union for them is an annual ritual in which individuals and organizations gather in story circles to reflect on the state of our union and poets create a collaborative Address to the Nation.

The U.S.D.A.C teaches those the grassroots to bring together arts and activism. They use artistic products to shift the public discourse, to change people’s minds and actions.

“We can integrate arts and culture into organizing strategies,” Horowitz says.

The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture asks people to imagine a society where art and culture are fully integrated into all aspects of public life. (Its website says U.D.A.C. was formed Oct. 5, 2013 in the middle of the federal government shutdown, which did not affect it because it gets no federal money and has no offices in Washington D.C., or anywhere else.)

The philosophy behind the work the U.S.D.A.C. does is that culture is a human right and everyone has the right to participate. The exercise of this key right “shifts our society from consumption to creation, competition to compassion, and isolation to interdependence.”

Or as Horowitz says on a video on the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture website, it is a “people-powered department aimed at harnessing the potential of arts, culture, and creativity to fuel empathy, equity, social change, and deliciousness (as he bites into a burrito).”

In Kalamazoo, he explains that by using performance as a strategy the idea is to move culture and art from the margins to the center of our public conversation.

And you don’t have to be a U.S. Citizen or an Artist to be a Citizen Artist with the U.S.D.A.C.

He invites those who enjoyed the process to become part of the U.S.D.A.C. by opening an outpost. All it takes is four people. As community support grows, a field office can be established.

“Begin by imagining the world you want to live in,” Horowitz says. “You will have company.”

Kathy Jennings is the managing editor of Southwest Michigan’s Second Wave. She is a freelance writer and editor.