Officials and bike enthusiasts tour Kalamazoo in search of the right bicycle plan

Bike ride through Kalamazoo sparks ideas on best ways to move bicycles through the city.

City and county planners, engineers, and bike advocates recently got their “Training Wheels” on and learned what happens when the bicycle rubber meets the road.

About 25 participants from Kalamazoo, Battle Creek, and as far away as Lansing-adjacent Delta Township, pedaled around downtown Kalamazoo when the city hosted a Michigan Department of Transportation Training Wheels one-day course July 20.

They were inside most of the day. Much of the talk was on very detailed AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and NACTO (National Association of City Transportation Officials) standards and practices for non-motorized networks.

But one can’t really know the best uses of bike lanes, sharrows, bike boulevards, and shared pathways unless you get on a bike and ride in the real world.

The 4.5 mile ride explored routes that are friendly to bicyclists but also traveled streets that only see the most fearless of riders. The class rode out around the start of lunch hour, when traffic builds to a frantic and somewhat “hangry” peak.

For the most part, aside from one driver on North Rose Street who obviously had no respect for Kalamazoo’s new five-foot-passing ordinance, motorists were mindful.

“Probably because we had the po-po with us,” community organizer Jo Ann Mundy joked, referring to one of Kalamazoo Public Safety’s finest bike-mounted officers who was on the ride.

Colin Harris, senior engineering associate with Alta Planning and Design’s Minneapolis office, led the bike herd. At a few spots he had everyone pull over, off the road, to discuss their comfort levels, 1-10, with the streets they’d just traveled.

The stretch of Pitcher Street just south of Kalamazoo Avenue and through the Michigan Avenue intersection had many of the riders a little freaked out.

It’s surrounded by commercial and industrial properties. The road has four lanes but no shoulder, a pedestrian sidewalk only on one side, and at one length is bordered at its edge by a concrete wall. It’s a busy artery for downtown, with average daily traffic at 11,600 vehicles. Speed limit is 30 MPH but drivers tend to go faster.

Harris says that a rider told him, “I would never ride on this street as a person on a bicycle.” A few regular riders say they had no problem with it, but most say they’d avoid it.

“Basically, I feel like I’m on a highway” Rebekah Kik, Kalamazoo Community Planning and Development director, says of Pitcher.

The group continued south to Portage Street. They gave a thumbs-up for the recent road diet, which turned the four-lane into a two-lane road, with center turn lane and two bike lanes. But it was thumbs down for how the bike lanes suddenly end before Stockbridge Avenue.

Stockbridge, as well as the new section of protected bike lane on Kalamazoo Avenue, and the new trail section that runs along Portage Creek (planned to be expanded, with completion in five years, to connect with the KRVT to the north and Portage’s trail network in the south, Kik says) were seen as nice, bikeable routes.

But spots such as the intersection of Rose Street and Michigan Avenue. were downright scary during the workweek lunch hour. And road surface quality, a constant complaint of drivers, showed its hazardous bone-breaking side as the bikers weaved around potholes on Jasper Street.

Bike it, plan it

Leading the classroom presentation was Tim Gustafson, senior transportation planner with Alta Planning and Design, Chicago office. He’s been a contractor with MDOT for seven years to lead Training Wheels courses in towns around Michigan.

Gustafson says Training Wheels takes city planners and engineers — and, he hopes, elected officials, but there were no elected officials on the Kalamazoo ride — on a variety of surfaces. He wants them to see examples of nice bike routes where lanes and other infrastructure have been laid, and to feel a bit of fear on those scary streets where no considerations have been given for bike travel.

“It’s very eye opening for some people who are very familiar with their city, but never experienced it by bicycle,” Gustafson says. “It really opens their eyes to what a shoulder feels like, to what a roadway surface feels like when you’re bicycling, how motorists perceive you when you’re on your bike even though you’re doing everything correctly.”

At the end of a day of AASHTO and NACTO concepts, plus real-world examples from Chicago and elsewhere, class broke up into groups for a mapping exercise.

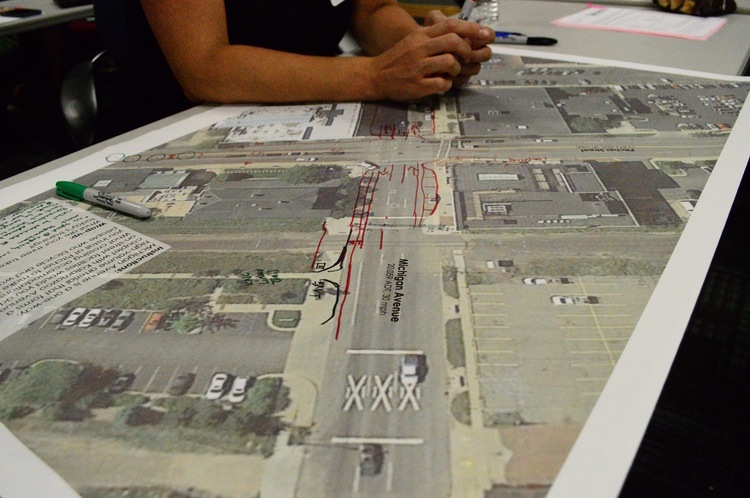

The group this writer observed, Steve Stepek (Kalamazoo Area Transportation Study senior planner), Christina Anderson (Kalamazoo city planner), Ben Clark (Oshtemo Township planner) and Ernie West (Delta Township engineer), were given a handful of multi-colored markers and a large printout of an aerial photo of the Pitcher/Michigan intersection.

Immediately Michigan Avenue went from being a one-way major traffic artery to being a two-way street, road-dieted with bike lanes. A median popped up — a nice gateway to the town, with trees and a pedestrian refuge. Pitcher was also road-dieted, with “bike boxes” (green pavement areas at a crossings to help guide bicyclists navigating busy intersections). Signs were put up to help guide riders to the new Kalamazoo Nature Center Urban Nature Park and the Kalamazoo River Valley Trail.

While marking out where a paved bike lane would be nice crossing the Michigan Ave. tracks, Anderson blurts out a bit of the reality the city faces: “The railroad won’t let us do anything.”

These improvements were just an exercise, all marker on paper. The real world possibilities are limited and sometimes halted by funding, demand for parking, and differing entities controlling area roads and tracks.

Some of the price tags for the installations that cities like Chicago could afford were shocking to the Training Wheels participants. Kik emphasized a few times that much of the Kalamazoo biking infrastructure she’s overseen, like the protected KRVT connection working its way through downtown, were paid for by grants and donations.

Earlier in the class, Gustafson illustrated the political realities these changes can face. He used Paw Paw’s road diet woes — in 2015 the village decided to reverse the diet after just six months due to negative feedback — as an example of why it’s important to get feedback from all members of a community.

Don’t “create enemies” by, for example, taking away parking, Gustafson says. He advises the class to spend “political capital” wisely. “Do your homework first,” he says after citing Paw Paw’s experience.

But there is a politically-winning argument for better biking infrastructure: It leads to better safety for all, he says. “Good roadway design that embraces bicycling also has the potential to be roadway design that makes it better for everybody. That includes pedestrians, that includes motorists,” he says.

Non-motorized travel networks, once established, also spawn more bicyclists. Safe routes “help unlock the potential for people who are not your hard-core bicyclists, but may be your more casual bicyclists, people who are interested, but concerned about their safety. Maybe make them feel a little more supported in the bicycling network.”

So, there are still Kalamazoo roads where non-regular cyclists feel they need a police escort for protection. But Gustafson, who has led Training Wheels groups in Kalamazoo before, says he has seen improvements.

For Harris, it was his first time pedaling around Kalamazoo. He says in an interview after the class that he enjoyed riding around the city, and he senses progress. “Lots of things (are) already on the ground. Lots of coordination, lots of leadership from the city, lots of coordination happening with the state,” Harris says. “Can’t say that for every city.”

Mark Wedel has been a freelance journalist working out of southwest Michigan since 1992. For more information, see his website.