Battle Creek groups and employers work together to make getting a GED easier for workers

When Battle Creek asked how could it be easier for workers to get their GED a solution emerged. Go to where they are–at work. And DENSO is one of the sites where GED instruction now takes place.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

The lack of a high school diploma or General Education Development (GED) certificate puts individuals at a distinct disadvantage and adds to the barriers they face as they try to get ahead, says Kristine Miller, an Adult Education Coordinator for the Community Action Agency of South Central Michigan.

To address these barriers a series of community meetings led to partnerships between the Battle Creek Public Schools, community organizations, and most recently the DENSO Corp. that are making it easier to earn a GED.

“Students who don’t have a GED or a high school diploma already have obstacles in their lives that they’re facing right off the bat,” Miller says. “So, if there’s any way for us to remove those obstacles so that they can take those next steps in their lives, that’s what we want to do.”

Transportation is one of those obstacles. Miller says this is why one of the four GED sites is located at Coburn School where the Community Action Agency has operated a Head Start program since 2017 to serve the parents of Head Start students.

But, not all of the GED students are parents of Head Start children, says Miller. “We also have people who live close to our location and we have people who come (to classes) because they know other people who have gone through the program,” she says, including two sisters who both earned their GED’s at Coburn.

“There are so many different reasons why students didn’t graduate from regular high school,” Miller says. “There may have been a pregnancy and they had to drop out. Sometimes their parents are sick and they dropped out to help their family. Sometimes they move and they’re not where they should be education-wise and they just drop out rather than continuing.”

More than 212,000 Michigan adults between the ages of 25 and 44 have no high school diploma or GED, according to the Michigan League for Public Policy, based on a report it issued in March 2018. Its data also shows that fewer than 7% of those individuals had enrolled in adult education classes.

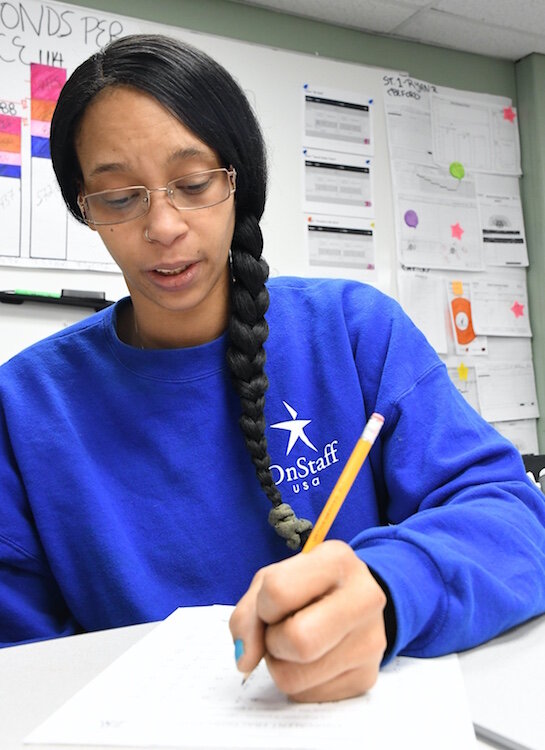

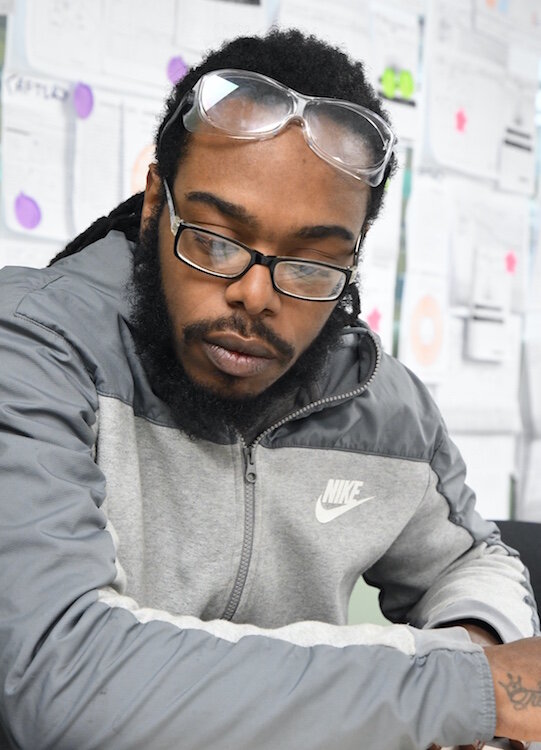

The ages and backgrounds of GED students vary. Some work outside the home, some are looking for work, and some are working to earn a GED so they can get hired full-time at a place where they may already be working. “The most common reason,” Miller says, “would be to obtain employment or to retain employment they already have.”

And some take the classes to prove something to themselves. “We had one lady who graduated and a couple of other people taking classes who said they just wanted to know for themselves that they could do it,” Miller says.

“Many parents say they want to show their kids how important education is. We have some with older kids and they want to be able to help them with their homework.”

Classes are taught by teachers provided by the Battle Creek Public Schools, which funds the GED program operated through its Adult Education Program at Coburn and sites at Miller Stone, the Battle Creek YMCA, the Calhoun County Correctional Facility, and DENSO.

More than130 students from the Battle Creek area and beyond Calhoun County are enrolled in the Battle Creek Public Schools Adult Education Program which offers the GED program.

Attendance at each location varies depending on what may be happening in the lives of the students. Miller says they typically serve more students during the school year. She says the Coburn program, which operates pretty much year ‘round, has graduated 17 people since it first began and currently has about 16 students who attend on a regular basis.

After the GED program began, class times were added to accommodate those students who work outside the home. “We wanted to offer a later time for people who work first shift,” Miller says.

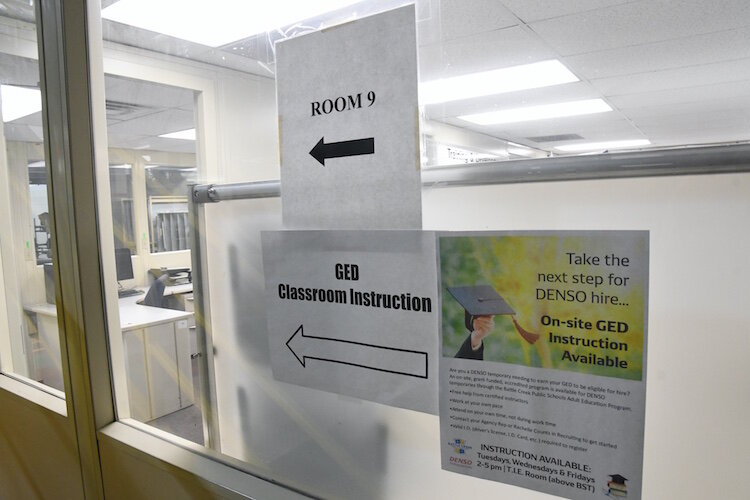

In March of this year, DENSO took the removal of obstacles one step further by opening a GED site at their campus in the Fort Custer Industrial Park. “We began at DENSO two days per week and 6 hours per week so we could get first and second shift workers in,” says Carol Poole, one of two of the on-site teachers. “Eight weeks ago we decided it would be better to offer classes three days a week.”

Since the classes began about two dozen temporary DENSO employees have attended the GED classes.

In June, three DENSO temporary employees graduated from the program with GEDs in a ceremony at the Miller Stone building, which houses BCPS administration offices. Once temporary DENSO employees earn their GEDs they become eligible for full-time employment opportunities as positions become available, says Nicole Brown, DENSO’s Talent Acquisition Section Leader.

Brown says leadership within DENSO had been discussing ways to address education and employment issues for at least three years. She says DENSO hosted a GED forum for the community more than a year ago. It brought together community and education leaders to talk about needs in the area which resulted in the formation of a committee and discussions with representatives of Battle Creek Unlimited, Calhoun County’s economic development agency.

At the time of that forum, Brown says the company was facing hiring challenges and had a large number of open positions to be filled. She says between 25 to 30% of the population is able and ready to work. The lack of a GED is the only thing standing between them and a job.

At DENSO Brown says they see a lot of interest from people who want to work there because they need a good job. “For us, the issue was their employability,” Brown says. “It’s harder than ever to get good associates and good people working and meeting eligibility requirements. It’s important for DENSO to be that community partner.”

Brown says the forum and the relationships formed there led to discussions with DeeAnn Wisler, Coordinator of the BCPS Adult Education Program. These discussions included a focus on DENSO’s temporary workers.

“I started some dialogs with (DeeAnn) about the large number of temporary workers in our building who didn’t have a GED,” Brown says. “In order to be hired in, they had to have that. They can be temporary without it, but they won’t be hired in until they’ve completed their GED.

“Deann and I spoke a few times. She came on site and said that they have some grant funding and instructors available if we could provide space. We brainstormed together and talked to management, looked for a room, and it all happened from there.”

Brown says 32 people have enrolled in the GED program at DENSO. She says each student works at their own pace and instructors assess their skill level to see where they need to focus their energy and attention. Four of those who have earned their GED have been hired.

“Anybody who has graduated from the program here we have been able to offer employment to,” she says. “We also have had a couple of people who have left DENSO since they’ve gotten their GED.”

Brown says if the company hires eight people and two go back into the community, it’s a win-win for everyone because those individuals who end up leaving have an enhanced skill set and a level of education that positions them to get ahead.

“We can be a stepping stone in growth for some people knowing that they will go back out into the community and how that changes the community,” Brown says. “If we can make a difference one person at a time that sets a good example for their kids and their families.”

Being a good example is what motivated Poole, now 77-years-old, to earn her GED. She says she dropped out of school in eighth grade due to a general disinterest in school. A series of life issues, followed by marriage, and children all kept her from continuing her education until her late 30s.

But, she says, “I decided I wanted to be a better role model for my kids. I wanted to make money and provide them with a good life.”

She earned her GED in two weeks and enrolled in 1970 at KCC. Four years later, she graduated from KCC and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in Special Education with an Elementary Education certification from Western Michigan University in 1975 followed by a master’s degree in Counseling Education and Psychology in 1990.

She went on to hold various jobs with the state of Michigan in education and also operated a private psychology practice where she worked mainly with youngsters. In 2000 she left her job with the state and closed her practice to care for her husband who was battling cancer. After his health improved, she went to work in 2002 for the BCPS where she taught until her retirement in 2012.

She soon discovered that she was not ready to fully step back and was hired by BCPS to provide classroom instruction to children who were suspended from school. She left that position in 2017 to work for the BCPS Adult Education program where she divided her time between Coburn and Miller Stone.

One year later, she was one of two teachers hired to work with the GED program at DENSO where the average age of her students is from 25 to 55.

Her classes can have as many as 9 or 10 students or as few as two or three depending on what other obligations students have on any given day. She says she also has students who come in two or three hours early.

“It varies,” Poole says of the class sizes, “depending on overtime and life issues.”

Her own experiences give her special insight and a unique understanding of their circumstances.

“What’s interesting to me is that our learning styles are a lot alike,” Poole says. “Things that were difficult for me to understand are the same things that are difficult for them to understand. It takes a lot of talking. I always tell them I’m everybody’s cheerleader. I just try to get them to understand that they really can do this, but things just got in the way.”

DENSO’s Brown said the instructors are an important part of the program. “I’ve just been so delighted, they’re such a positive force for people to reach this milestone,” she says.

Brown says the payoff for her is the looks on her students’ faces when they succeed. “Once they complete that high school diploma they’ve got a job, raise and benefits and money to raise their children,” she says.

“DENSO does a $3,000 tuition reimbursement for a field related to jobs there and there’s the ability to move up through the factory which is just incredible. It’s just life-changing for them.”

People who earn a GED or other high school credential will earn more than $6,000 a year on average compared to those who don’t have that education, according to the state of Michigan’s Workforce Development Agency. Additionally, the agency says that most training programs for licenses or certificates also require a high school diploma or its equivalent.

Many of the students who go through the Battle Creek-based GED programs go on to earn certifications or two or four-year degrees.

“One of our students who graduated actually is working for CAA in one of our early childhood rooms. She’s at Kellogg Community College to obtain an Early Childhood Education degree. Another one is going to Lansing Community College to become an American Sign Language interpreter,” says Miller of the Community Action Agency. “We have another girl who’s also interested in taking classes at KCC.”

GED Instructor Poole says in addition to those companies who will become the GED graduates’ future employers, the community and the students also benefit.

“They become better citizens because they’re happier with their lives and their self-esteem is growing,” she says. “I think it’s the best thing that’s happened in Battle Creek in a long time. I wish we could get more buy-in from other manufacturers because they get better employees and everybody wins.”

Photos by John Grap of John Grap Photography. His work is featured here.