A cowboy at heart, Murphy Darden’s collection celebrates all that’s possible for African Americans

Artifacts from the first black astronauts, the Buffalo Soldiers, and the first African American millionaire are just the beginning of the Darden collection acquired over many years by the 90-year-old.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Northside series.

In another life, Murphy Darden might have been a cowboy.

As a boy, Murphy and his twin brother, Irvin, wore cowboy suits to school, played Cowboys and Indians, and took turns sneaking into the Elkins Theater in Aberdeen, Mississippi to watch Westerns on Saturdays. “We loved seeing the cowboys,” he says.

Glancing around Darden’s Lulu Street home, it’s easy to spot the evidence of his passion. Auction books, cowboy memorabilia, and six-page movie posters of black cowboy stars line the walls. In the basement, large cardboard cutouts and original saddles, as well as slave ship models and diagrams, fill shelves and glass cases.

He’s happy to discuss any piece that catches a visitor’s eye.

On a shelf above the loveseat sit model replicas he constructed of the first African American churches of Kalamazoo. Over the fireplace, next to a portrait of Muhammad Ali and a bust of him that Darden carved out of wood is a mounted red punching glove with Ali’s original name, Cassius Clay.

Darden has artifacts from the first black astronauts, the Buffalo Soldiers, and the first African American millionaire, Madam C.J. Walker, a philanthropist who made her money from beauty and hair products, just to name a very few of the types of pieces he’s amassed.

His pieces celebrate African Americans and all that is possible, even in the face of adversity and discrimination, and they also point to a darker past when segregation and intolerance were commonplace aspects of American life.

He’s proud of his extensive collection, which he guesses likely totals up to 1,500 artifacts. At 90, he’s slowed down his collecting and is, with the help of the Kalamazoo Valley Museum, creating an inventory of his artifacts, a long but satisfying job.

And it all started with a love of the cowboys.

Growing up in Mississippi

Growing up during the Depression in Mississippi, the Darden twins picked cotton, delivered groceries, mowed yards and scraped melons, saving their money to afford a 10 cent movie ticket. As identical twins, they then managed to get two for one because one of them would leave their hat at the ticket booth and send the other one to go up to fetch it.

At the time in the segregated south, there were two separate theaters, one for blacks upstairs and one for whites downstairs.

“I didn’t really see much violence, though I know there was some,” he says of growing up in Mississippi. “I didn’t see it because you’d stay in your place. Yes sir, no sir, step off the sidewalk when you see a white coming. And you ride in the back of the bus.”

At the theater, life was full of possibility. Darden remembers Wild Bill Elliott, the Three Musketeers, the Lone Ranger, and the singing cowboys, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. But Darden never saw an African American cowboy on screen. “I didn’t know then there were black cowboys.”

He certainly didn’t know then that in the 19th Century and heyday of the Wild West, nearly one in four cowboys was black, according to the Smithsonian Institute. In the 1860s and 1880s, former slaves who had experience with herding cattle headed West for jobs in an industry that is reported to have had less discrimination than other occupations of the time.

Herbert Jeffries, sensational singing cowboy

Both Murphy and Irvin were drawn to art and collecting as boys. Their mother raised them while working as a cook for a white family. The twins collected the tops of ice cream cups, which featured photos of movie stars. “We enjoyed naming pictures at night. Who is this? Who is this?”

When they collected 12 tops, they could turn them into the ice cream man for a full-sized poster. “I didn’t care for the women. I just wanted the cowboys,” Darden says.

With art as their favorite subject at the Aberdeen Colored High School, the boys both began drawing the faces of the stars they collected. An interest in cowboys soon led to seeking other collectibles.

When Murphy and his wife Manassa, and then Irvin and his wife, moved to the Northside of Kalamazoo in the late 1930s, their penchant for collecting grew as together they roamed antique stores and flea markets and attended auctions searching for cowboy and African American memorabilia.

Both men worked at the Harris Hotel, and then later at Kalamazoo Vegetable Paper, Co., which was eventually purchased by James River, Co.

“One day, I collected a hardcover book that had white cowboys,” Darden says. “But as I was reading it, I came across this name, Herb Jeffries, who was a black cowboy in a low-budget Western.

“Wait a minute, I said. A black cowboy named Herb Jeffries. Wow!”

Reading more about Jeffries, Darden discovered he was a light-complected cowboy who sang with the Duke Ellington Band and was known for his stellar voice. “Perry Como even said, ‘I wish I could sing like Herb Jeffries.’” Turns out, Jeffries was born in Detroit.

So Darden began collecting classic movie books to discover more about Jeffries. “And then I saw where you could order a tape. When I saw that, I ordered one. I hadn’t seen a black cowboy before. I didn’t know how they dressed.”

Jeffries, Darden discovered, made four cowboy movies, Harlem on the Prairie (1937), Harlem Rides the Range (1939), Two-Gun Man from Harlem (1938) and The Bronze Buckaroo (1939). Darden has seen all but the first one, which unfortunately has disintegrated beyond repair.

“When I saw that tape, I looked and he was dressed so nice. He was dressed in black. Ten-gallon white hat. And a white horse named Stardust. He had a black sidekick named Dusty.

“And all the villains were dark-skinned. Just like a movie. And he could sing. And his sidekick was funny. He wore nice outfits. He could ride, shoot and fight,” Darden says. “I love that cowboy.”

The more Darden learned about Jeffries, the more he took an interest in learning about other black cowboys, both real and in movies, and then about black Civil War soldiers, and about Buffalo Soldiers, nicknamed by the Native Americans, who were black soldiers that fought Native Americans on the frontier from 1867 to 1896. One thing led to another and with each learning curve, Darden’s collection grew.

Local African American History

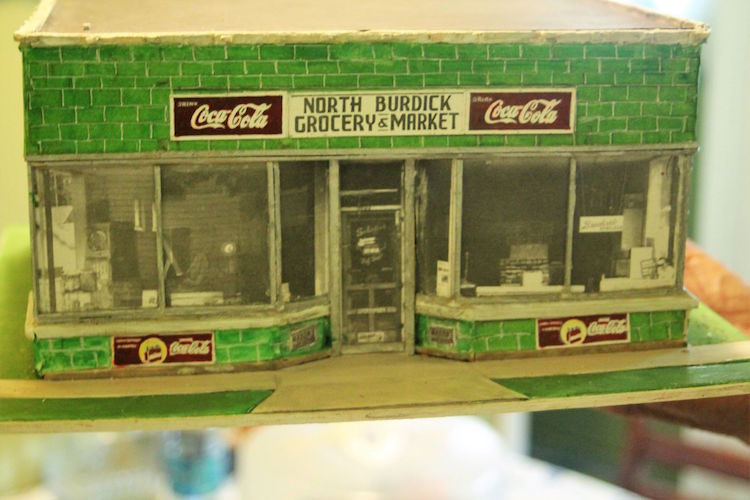

In addition to his collection of important national African Americans and related events, Darden is proud to have collected pieces from buildings and events important to the local African American community. He has stained glass windows of both the original African Methodist Episcopal Church and the original Galilee Baptist Church. He has artifacts from the house of Oshtemo’s first black settlers, Enoch and Deborah Harris. He also made a model of the Harris house before the Oshtemo Fire Department used the building in firefighting practice, a loss Darden is still sad to recall.

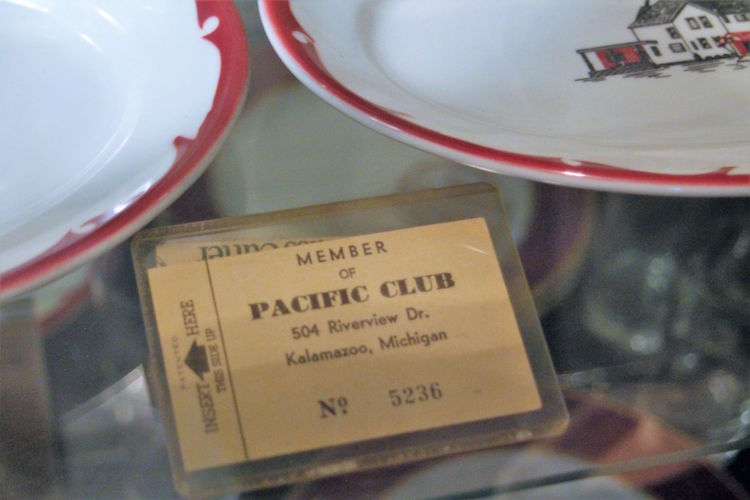

He also has several dishes and plates from the Pacific Club, an elite black club formerly located on Riverview Drive and East Main in the 1950s. “You could go to the club, but you had to have on a suit and necktie,” says Darden.

Darden’s pride in the area comes from seven decades of living on the Northside, raising four children, and being involved in church life of Bible Baptist Church as a charter member. He not only remembers the old buildings, he has history in them.

When the old Douglass Community Center, originally built as an activity center and dance hall for African American soldiers stationed at Fort Custer, was about to be torn down, Darden went by one day and saw a man outside.

“I said, ‘I’d like to have something from this building, something to remember it by.’ He said, ‘What would you like to have? Big or small?’

“He went back there and he brought the drinking fountain back to me. And he gave me the exit sign. The fountain is the best thing because this is part of the original building. The soldiers drank from this.”

The fountain now stands in his basement with a photo of the original mosaic behind it from the old Douglass.

“That’s the kind of stuff I like.”

Growing a museum

Irvin Darden’s collection of Negro League Baseball and Kalamazoo Lassie (the all-woman Kalamazoo baseball team) memorabilia is now housed in the Kalamazoo Valley Museum. Sadly, Irvin passed away in 2015 and Darden not only lost a dear brother but a partner in collecting.

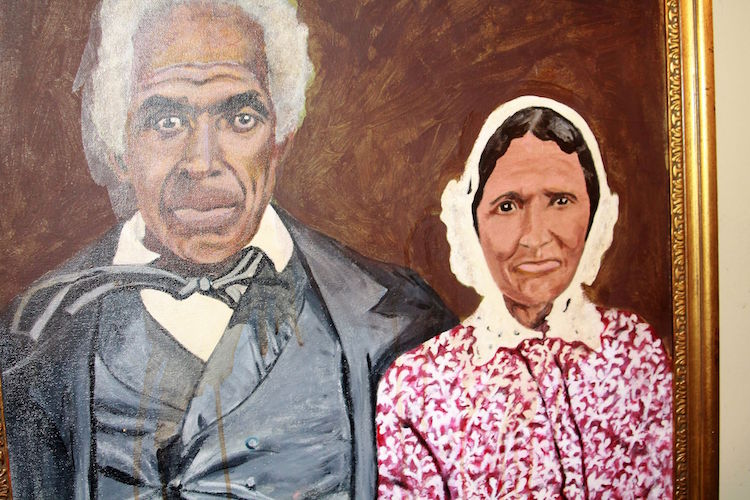

Murphy’s extensive collection of African American memorabilia, both local and national, and his own history-inspired artwork, paintings, carved busts and building models, currently fills most of his house, including his entire basement. He has been trying to find ways to create a museum for it for years. Meanwhile, his house has become a museum of sorts. His guestbook has names going all the way back to 1963.

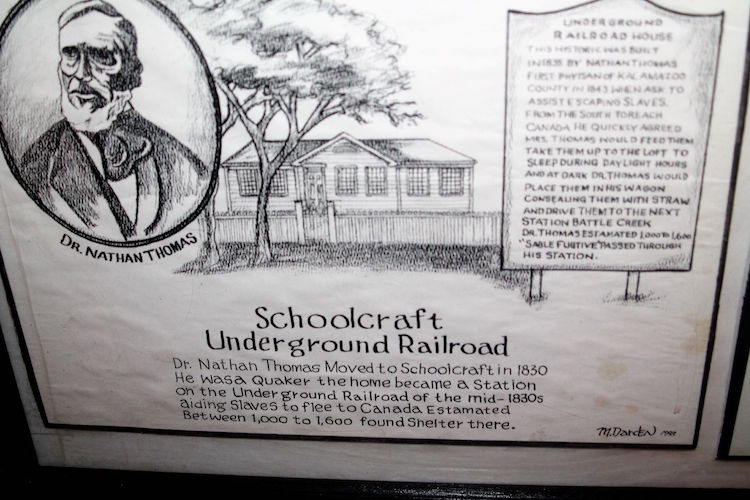

Murphy’s pieces also are on display at various venues around town including the Douglass Community Association, Northside Association for Community Development, the Kalamazoo Air Zoo, the Dr. Nathan Thomas House, which is the Underground Railroad Museum in Schoolcraft, and the traveling museum of the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, among other places.

For a while, Darden visited schools with his life-size cardboard cutouts of African American cowboys telling the stories he’s learned along the way.

As a head painter for the James River Company before he retired in 1993, Murphy borrowed blueprints to create a replica of the company buildings out of wood, a model which is now encased in glass at the Parchment Public Library alongside a portrait of Jacob Kindleberger, founder of the Kalamazoo Vegetable Paper, Co., the predecessor of the James River Paper Co., and a portrait of Murphy Darden, James River head painter.

When Darden and his brother first were hired at the paper mill, they could only work as janitors because of discrimination. In the 1950s, that began to change and Darden applied for a painting job.

“It’s funny they have a portrait the founder of Parchment and a painter,” Darden says, chuckling. “They’re not going to remember the supervisors and the president. But they’ll remember me and Kindleberger.”

Murphy says there isn’t a lot of African American history displayed in the Kalamazoo area, but he’d like to see more. “What have we got in Kalamazoo that is related to us? Sure, they have a few items at the Kalamazoo Valley Museum. They have a few at Douglass (Community Association), but not a whole lot.”

When students associated with the Kalamazoo Valley Museum finish helping him inventory his work later this month, Darden hopes to find that his beloved collection may have finally found a home.

“For all this to be documented and insured is a huge blessing,” says Darden. “This has been a tremendous help.”

What will he do with all that empty space once his collection is gone?

“I guess I’ll have to start all over again,” he says, laughing.

Cowboy, after all

“I kind of wanted to be a cowboy, but I never owned a horse,” says Darden.

Then he tells a story. “When we were seven or eight, my mother rented a house from white folks and a farmer would come after us and pick us up in his car when his cows got into someone else’s pasture.

“So we’d go hustling cows in the pasture. Cows and the boys. Wait,” he says chuckling. “That is a cowboy. And we were good cowboys!”

Theresa Coty O’Neil is the Project Editor for On the Ground Northside.

Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s “On the Ground Northside” series amplifies the voices of Northside Neighborhood residents. Over four months, Second Wave journalists will be in the Northside Neighborhood to explore topics of importance to residents, business owners, and other members of the community. To reach the editor of this series, Theresa Coty-O’Neil, please email her here or contact Second Wave managing editor Kathy Jennings here.

For more Northside coverage, please follow these links.

Longtime residents who choose the Northside create the backbone of the community