Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

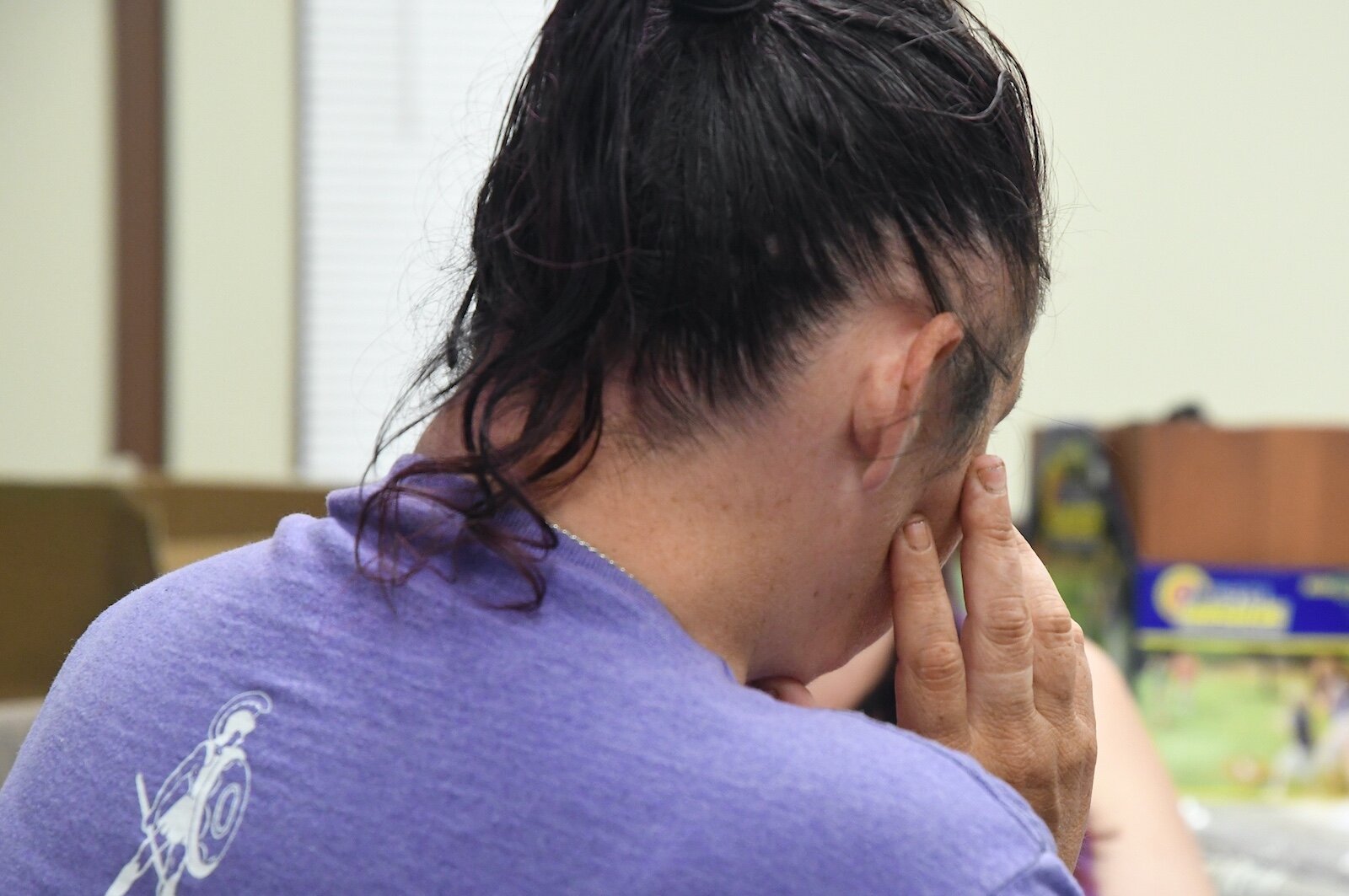

Nikki did not want her last name used, but she does want her story told so that she doesn’t end up as a mere statistic in a recently released report from the Michigan Association of United Ways which finds that a little more than 50 percent of households in Battle Creek are struggling to cover the cost of basic needs.

The report titled “ALICE in the Crosscurrents: COVID and Financial Hardship in Michigan”, is the fifth in an ongoing series of yearly reports distributed by MAUW which provide information about the number of people living at or below the ALICE threshold (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed). The report includes a Survival Budget and a Stability Budget, each of which lists the cost of basic monthly expenses such as housing, food, transportation, healthcare, and technology for households with a single adult; two adults; two adults with two school-age children; two adults with two children in child care; and a single senior or two seniors.

Nikki says she is getting by on $1,100 in social security disability that she receives each month. This is $1,061 less than the Survival Budget for an individual which reflects the cost of getting by and $27 more than the federal poverty level for a single person. Her income doesn’t come close to the Stability Budget which offers a snapshot of the cost of maintaining financially with the opportunity to begin saving.

She found herself unhoused after she and her father were evicted in June 2022, from the house they shared in Battle Creek because of code compliance issues. She says she moved in with him after her lease was up to help him out and “it just went left from there.”

“I was sleeping in my vehicle and coming down here,” Nikki says of the S.H.A.R.E. Center, a daytime shelter that provides meals and offers a wide range of resources. “I went from there to living with my aunt, but she’s got to move this month so I’m not sure where I’ll be after that.”

In between her stays in the vehicle and her aunt’s house, she was living in a shed and also slept in the elevator of a parking garage. The turn of events has been mind-numbing and frustrating for someone who says she has always been able to support herself. Right after she graduated from high school she went to work for a local manufacturing company and was let go because she has learning disabilities and health problems, but she continued to find work.

“I want to get housed and off the streets,” Nikki says. “I ain’t never slept under a bridge and I don’t want to.”

“Her biggest obstacle is definitely the income side of it,” says Lacey Kequom, a Case Manager at the SHARE Center who is working with Nikki. “It’s getting the qualifications to afford that home. All of these background checks go into it. A lot of landlords don’t work with our clients and don’t understand their situation.”

Nikki and Kequom recently tried to do an online application that cost $60. While that may not seem like a lot to most folks, Nikki says it is for someone like her on a fixed income.

At least 80 percent of the individuals Kequom works with are below the federal poverty level. She says she hopes this latest ALICE report will increase awareness of the daily struggles experienced by her clients.

The 30,000-foot view of struggles on the ground

Alyssa Stewart, Chief Impact Officer for the United Way of South Central Michigan, says, “We are going to be doing a lot of community conversations and presentations with decision makers and policymakers so folks will see and hear us. We want to get the word out about the ALICE information and see where we can inform decisions.”

The UWSCMI also will continue to use the ALICE report to inform grant-making and where it should invest dollars to make the greatest impact, including direct service programming to assist clients of many nonprofits funded by UWSCMI, she says.

“We’ll continue to advocate with corporate partners to understand the ALICE workforce and partner with us to implement solutions to help the workforce in a meaningful way,” Stewart says.

The findings in the most recent ALICE report are based on 2021 data with COVID looming large in the data gathering, says.

“So for many folks, we think about how many things have changed since 2021,” she says. “Inflation and the cost of living have likely gotten even more exacerbated in recent years. 70 percent of the jobs we have in Michigan pay below $20 an hour and that greatly contributes to the overall state economic situation. Even in 2021, we saw an increased cost of living. Wages below $20 an hour mean budgets are going to need to be subsidized by the government and nonprofit sector. This is really a sign that something is broken. In an ideal world, wages catch up and inflation slows.”

While job disruptions and inflation delivered significant financial pain, a combination of pandemic supports and rising wages did help to blunt what could have been a deeper financial crisis, the report finds. However, as some benefits are peeled back, and inflation persists, financial strain may continue to plague Michiganders below the ALICE threshold.

“These hardships, including access to food, healthcare, and education for ALICE families were often hidden in plain sight until the pandemic,” said Hassan Hammoud MAUW CEO, in a press release. “Equipped with the ALICE name and data, we can do even better to develop effective policies and track our progress toward reducing financial hardship in Michigan. We have an opportunity to build on what was learned during the pandemic as ALICE continues to face economic uncertainty.”

Stewart says individuals at the lowest end of the spectrum benefitted significantly from pandemic-related specific efforts.

“And yet a lot of those special tax credits and other pieces were rolled back in 2022 and 2023. We may see in the next ALICE report that some of these pieces will be temporary,” she says. “The cost of living in 2021 in Calhoun County was lower than neighboring counties. Housing and childcare costs were slightly lower and that can speak to the experience of folks in Calhoun County where their dollars may go further.”

For William Pernell, the cost of living in Battle Creek is a daily struggle. He has been legally blind since age 3. Now 27, he says he has worked odd jobs and considers himself an entrepreneur. He has been trying to get social security disability for 20 years and says that extra money would make a real difference.

He moved from California to Battle Creek to be closer to his biological family and had been living with his mother. But, they weren’t getting along and he moved out and has been staying wherever he can, including in a shed.

“That’s how I became homeless,” Pernell says. “I do what I got to do to survive. When I’m about to come off my last dollar for what I need, I find a way to earn money. There’s a will where there’s a way and my name is Will and there’s a way. It’s not about what needs to be done. It’s what can be done. I stop taking things for granted.”

He comes into the SHARE Center for meals and assistance with needs that include access to those social security disability payments which have yet to materialize.

“This happens all the time. The processes are insane,” Kequom says. “One thing I’ve never understood about social security is that they don’t want people applying for disability payments to work for 15 months. How are people supposed to manage? I’ve been asking these questions for four years.”

Pernell says he receives food stamps and even with that he says, “I had to go to hell and back to get that.”

The challenges to individuals like Nikki and Pernell are part of a larger set of issues including a federal poverty level that is not an accurate or realistic metric, Stewart says.

“I think ALICE highlights that pretty significantly when you look at how low our Survival Budget is,” she says. “To say that someone who makes $10 more than the federal poverty line does not need assistance doesn’t make sense. It feels arbitrary whereas ALICE is based on real local data.”

Stewart says she thinks eligibility criteria based on the federal poverty level exclude people that could use that assistance.

“There definitely is a lobbying effort going on to increase the federal poverty level numbers. When it’s raised, millions more people will be eligible for services. It seems those folks really need the assistance,” she says.

That assistance is critical to giving people the tools they need to lift themselves out of poverty and set them on a path out of financial insecurity, Kequom says.

Stewart says the UWSCM offers a broad range of assistance programs that are grounded in ALICE data, including help with utility payments and access to food.

“We give out millions of dollars each year in assistance to households. We’re able to partner with Consumers Energy and receive state funding for that. Energy insecurity causes a lot of stress and anxiety for people,” she says. “One thing that consistently comes up is the toll of living in our world and country as an ALICE household. The absolute weight of that and the toll it takes on a person’s mental health puts them into a constant state of insecurity.

“We’ve really been trying to re-center folks. The numbers are alarming and compelling. It’s real people and so many people. Tens of thousands of households in our community are carrying a significant invisible weight and saying, ‘I’m on the razor’s edge.’”

Small wins, more to be done

Even though the number of ALICE households in Battle Creek increased from 47 percent to 50 percent based on 2021 data in the latest ALICE report, Stewart says there is still reason to be optimistic.

“For Calhoun County, there is something to celebrate in that the rate of households living in poverty is trending downward. There were 600 fewer households living at or below the poverty threshold. They had transitioned out of poverty and into the ALICE space.”

The number of ALICE households increased by 1,800 in Calhoun County, according to the ALICE report. 2019 data used in the 2022 report found that there were 14,078 ALICE households versus 15,902 in this year’s report.

Stewart says this lift out of poverty and into the ALICE space is due to an increase in the household median income in Calhoun County which went from $49,000 to $50,902. Although below the state average median income of $63,498, Stewart says the positive is that as of 2021, “Folks in Calhoun County were making more money and some saw an increase in their pay.”

“Many of those lower wage earners received quite a bit of assistance in 2020 and 2021. That helped a lot of families and that may speak to where the reduction in poverty came from,” she says.

As these families and individuals work to get themselves into a financially stable space they continue to rely on services provided by nonprofits, including the SHARE Center.

Stewart says Calhoun County has a vast network of nonprofits that are providing core basic services, including food, clothing, childcare, healthcare, housing, and job training. While their efforts are providing a safety net and taking the pressure off of those on really tight budgets, their capacity is being tested.

“Each nonprofit is different. In general, what we’re hearing from our nonprofit partners is that they’re absolutely struggling to keep up with the demand,” Stewart says. “Funding sources can be very volatile and fundraising can be very difficult. Donors might be feeling like it’s a little more difficult to give these days. The demand just seems to be growing and growing and growing.”

Kamisha Minix, who found herself unhoused after escaping an abusive relationship, says people don’t understand what people like her go through.

“There needs to be more assistance, programs, and workers to help people like me,” she says.

She sought help from S.A.F.E. Place in Battle Creek after escaping the abuse she endured in Kalamazoo.

“I was without a place for two years. I was on the streets. I slept in abandoned houses and sometimes drug houses,” Minix says. “I almost resorted to prostitution, but I didn’t. God has kept me going.”

She shares that she did suffer a nervous breakdown and received treatment through Summit Pointe. It was during this time that she met Hali Felch, a Permanent Supportive Housing Specialist with Summit Pointe, who got her into SAFE Place.

Minix says Felch helped her get into an apartment. She lives on social security disability payments of $780 a month, 30 percent of which goes to cover the cost of her rent with Summit Pointe picking up the remainder.

To make ends meet, she says she goes to food banks.

“That’s hard, but I do it,” Minix says.

Like many of those who are experiencing the type of financial insecurity others can’t begin to understand, Minix says she feels invisible.

The reality, Stewart says, is that there are a lot of people living in the sub-middle class space. “We are making sure that we don’t lose sight of the human element. This is a reminder to us all that these are real people.”