Editor’s Note: This is the first story in our series, Sacred Earth which will examine the intersection between climate change — and faith, worldview, philosophy, psychology, and the creative arts. This series is sponsored by the Fetzer Institute, whose mission is to help build the spiritual foundation of a loving world.

Faith institutions around the world are taking up the call to act on climate change.

Scholars, environmental organizations, and scientists are seeing faith communities and indigenous cultures as offering a practical and moral imperative on the climate crisis. Faith combined with science is what some say has the potential to be — quite literally — our saving grace.

More than 80% of the world’s population identifies with some sort of religion. Faith institutions are influential, value care for creation, and also offer an antidote to “climate doomerism,’ by providing a community of support for people to take up what is likely the work of a lifetime. Faith institutions and indigenous cultures can also help give the earth care work a sense of meaning and purpose, which creates resiliency and inspires hope.

“If we each offer the best of our respective traditions, we may yet see a way through our difficulties,” according to the Islamic Declaration on Climate Change. “Individually, we are called to ‘ecological conversion’ in our daily lives,” wrote Pope Francis. “We should not think that our efforts — even our small gestures — don’t matter.”

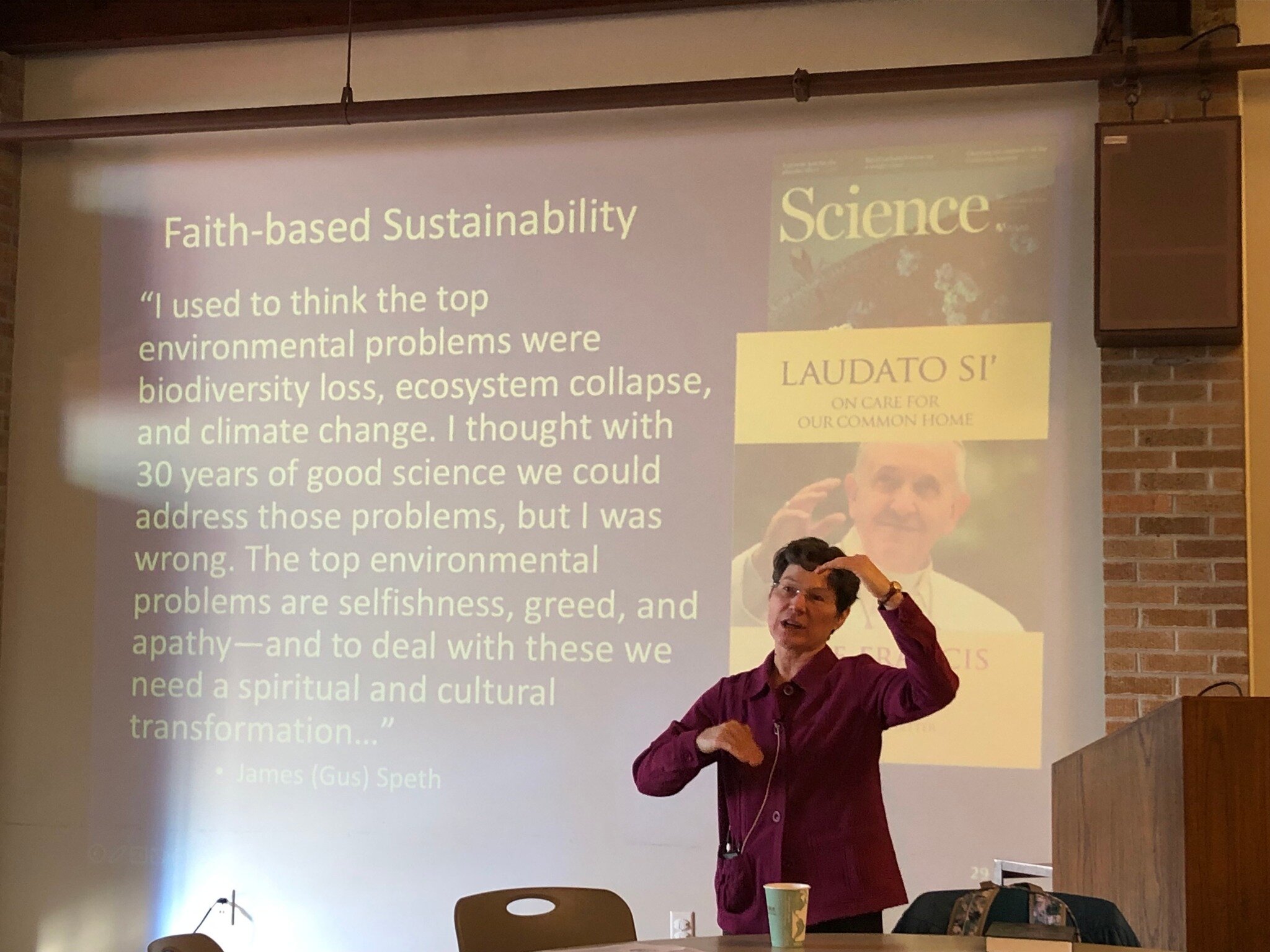

Dr. Cybelle Shattuck, author of “Faith, Hope, and Sustainability: The Greening of US Faith Communities” is an assistant professor at Western Michigan University and holds a joint position in the Institute of Environment and Sustainability and the Department of Comparative Religion.

Shattuck has devoted much of her academic life to studying the intersection between religion and sustainability. She was motivated by these questions: “When people of faith actually adopt an environmental ethic in their congregations, when they make care for the earth part of their congregations, what motivates them? What are the processes they use? What are they doing?”

For her book, Shattuck visited and researched over a dozen faith communities with impressive sustainability movements, including green sanctuary, creation care, resource preservation, waste reduction, and native plantings, all focused on changing their relationship with the environment.

That research was foundational to how she came to understand the ways faith communities take up the ecological call and also sustain and support climate change and sustainability efforts.

Shattuck has identified three areas in which faith (and faith institutions) intersect with, supplement, and support ‘care for creation.’

Number One: Stewardship

The first area in which faith institutions on both sides of the political or theological spectrum can agree is stewardship. Christianity values ‘care for creation.’ Islam instills the values of earth care in its followers through stewardship, balance, and moderation. Buddhists, while known for the value of ahimsa, the principle of non-violence for all beings, also have a strand, Engaged Buddhism, that counts the ecological crisis among its top priorities.

In the Jewish tradition, Shattuck points out, festivals are tied to the seasons: Passover is in spring, and harvest festivals are in the fall, to promote the relationship to the earth as it moves through the seasons.

“People develop what we call eco-theology,” says Shattuck. “With the stewardship ethic, God gives humans dominion, but we’re stewards of God’s creation to take care of it.”

Connection and relationship with nature are important features of stewardship. “Jesus goes out into nature to have this connection with God, Hebrews lived in a pretty agricultural world. It was important to fallow your land every seven years. If you plant fruit trees, you have to wait before you reap. Animals get the sabbath off, not just humans.”

In Genesis 1 and 2, which recounts the creation story in the Bible, God gives humans dominion over the earth. “Earth isn’t ours. Earth is God’s creation,” says Shattuck. “In Genesis 2, you have to tend and care for the earth. You’re supposed to look after the garden, and animals are companions of human beings.”

Number Two: Faith, hope, love (thy neighbor), and sustainability

A second way in which faith traditions connect with earth care is through religious teachings, such as “Love your neighbor” in the Christian gospel and Jewish teachings. Hindus teach that when you are loving others, you are loving God. This lens leans toward social justice.

“It looks at how climate change affects people differently depending upon their resources,” says Shattuck. “Some people get hit harder by the effects of climate change and some people have fewer resources to respond to it. People in the developing world, for instance.”

Shattuck cites the example of Hurricane Katrina, exacerbated by climate change. “It turns out the winds are moving slower, the storm sits in place and drops more of that water.”

But those who were most endangered struggled to evacuate. “If you wanted to evacuate, you had to have a working car and be able to afford a hotel room. People who were left behind tended to live in lower areas, with more damage, less insurance, and less capacity to navigate the insurance system, the FEMA system, didn’t have jobs that would give them time off, no computer to do paperwork, maybe not high enough education level to navigate the systems,” says Shattuck. This type of situation is occurring all over the world in response to climate disasters.

An example of a church that has a movement through the social justice lens regarding climate change impact is the Catholic Church, with its Catholic Climate Covenant, a pact that predated Pope Francis but which he has expanded upon in his teachings. “Catholic Climate Covenant helps U.S. Catholics respond to the Church’s call to care for creation and those most affected by the climate crisis,” according to its website. “We are grounded in the Church’s deep history of teaching on creation, ecology, and the most vulnerable.”

Caring for the earth is an extension of the value of caring for others, especially those most in need. “Climate change exacerbates all of these issues that the faith community has been working on forever,” says Shattuck. “We are putting fossil fuel in the atmosphere and destabilizing the climate system and harming people in the developing world.”

“If you love your neighbor, how is our behavior, even if indirectly, harming people who we should care for? If you care about your neighbor, you can’t be damaging the ecological systems that damage food and water that make it possible to live.”

Number Three: Communion with nature

“I’d rather be in the mountains thinking about God than in church thinking about the mountains,” wrote John Muir, known as “John of the Mountains” and also “Father of the National Parks.” Muir was a Scottish-born American naturalist and environmental philosopher who established both the National Parks and the Sierra Club.

In this third way of earth care intersecting with theology, the premier value is to “preserve the environment because nature is where we have our spiritual experiences,” says Shattuck. This third entry point appeals to naturalists, nature mystics, artists, preservationists, and contemplatives.

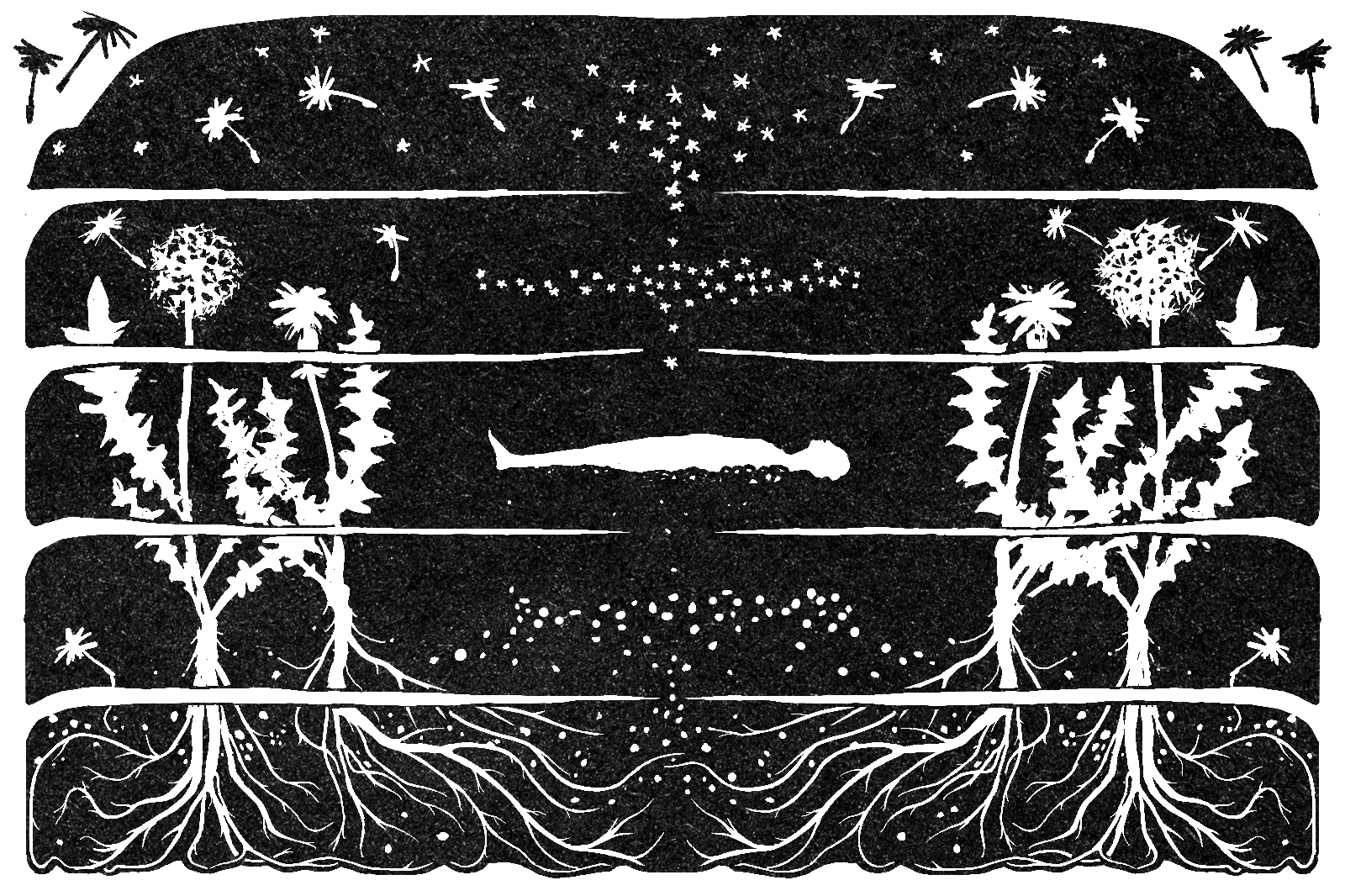

Jesus went into the desert to commune, and Buddha sat under a bodhi tree. “You connect to the creator through the creation,” Shattuck says. People’s awareness of nature, such as birds migrating in a different pattern, seasons coming at the right time, and planets appearing on schedule, are part of this holistic system.

Sadly, “We’re damaging that holistic system,” says Shattuck. “We’re ruining the harmony of God’s creation.”

Shattuck quotes Sister Ginny (Virginia Jones), of the Sisters of St. Joseph, a Kalamazoo congregation formerly housed on Gull Road. Sister Ginny is one of the mothers of the Bow in the Clouds Preserve now stewarded by the Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy. Shattuck recalls Sister GInny saying, “To change the way our society treats nature, people have to regain that spiritual connection to nature.”

In some circles, this orientation has been called eco-spirituality, eco-sensibility, and even eco-imagination. These avenues prioritize reimagining our relationship with the natural world so that we understand its interconnectedness.

As Sister Ginny said when she spoke with Second Wave in a 2019 article, “The whole point of Bow in the Clouds is that we wanted people to experience being one with their whole earthly community through God’s relationship with all of creation — and we’re a part of that.

“You don’t have to belong to the Christian tradition to appreciate this interconnectedness. You can be a Buddhist. You can be a Hindu. All major religious groups have a sense of contact with the Holy through the natural world.”

What inspires faith institutions to take up climate issues?

Through Shattuck’s intensive research, she’s discovered a few common reasons that faith communities become inspired to take up the environmental mantle.

“Fear can motivate people to start something, but it doesn’t keep them going,” says Shattuck. “A minister I spoke with said that so much the way we talk about climate change is how do we make things less bad. That doesn’t sustain people over time. We have to show them what are the good things.”

To keep them going, people need vision, community, and hope.

“Religion is about a vision of a society where everyone’s needs are met, where everyone can thrive, where everyone is living according to moral values,” says Shattuck.

“One of my observations from the groups I’ve studied is that faith is not always the first motivation for people. It’s something they love that they feel is in danger. There is a threat to the children’s future or there’s a threat to the natural world that they can’t imagine living without.”

Fear might attract people to the movement, but faith can often keep them moving.

How faith and community support environmental work

“People who come to this work from a faith community find that their faith helps sustain them in this work for the simple reason that they have a community, and fellowship to share concerns, fears, and hopes,” says Shattuck. “They have a vision and have a sense that they are not alone in this journey.”

With others, “you begin to realize this is the work of a lifetime. We are going to be addressing a changing climate for the rest of our lives.”

Groups such as these offer support and encouragement through shared resources, earth-friendly projects, and community. Shattuck observed another factor sustaining people in the work. She gave the example of a Presbyterian church she visited in Virginia.

This church had been doing two decades of earthwork when Shattuck met them. A committee of 12 people was taking on a national energy policy to reduce air pollution. They were connecting with other congregations. The minister was fond of saying, “God calls you to be faithful, not to be successful.”

“Even if you don’t know if you can accomplish something, you have to try. Because that’s what being faithful means,” says Shattuck. “And if God helps, you might achieve a lot more than you thought you could with this small group of human beings.”

Shattuck sees this as a meaningful defense to climate despair. Kalamazoo experienced record-low snowfall this winter. The previous summer, most of us were checking the weather report for air quality due to smoke and haze from Canadian wildfires. Southwest Michigan is not immune to climate impacts, but anxiety around these issues can cause despondency, inaction, and paralysis.

“We have to at least try and we have to live our values, that is doing the right thing to do even if we don’t know if we can succeed,” Shattuck says. At the church she visited, faith and community “gave them the courage to try and take the next step and the next step to keep going.”

Shattuck points out that faith groups also offered a support system on both a community and a psychological level that helped counteract climate despair. What you are doing matters, “even though you didn’t get to elect the person you hoped to or get the policy you hoped to, you were living according to values.

“This demonstrated the importance of finding a community group and the importance of standing up and living our values even if we’re not sure it will make a difference.”

Hope for Creation: Planting interfaith seeds

In Kalamazoo and other communities, various faith communities are coming together to share resources, support, and a mutual commitment to earth care, which often transcends political and theological differences.

Hope for Creation, a Kalamazoo grassroots, interfaith, inter-religious group working to encourage and support faith-based action on climate change is celebrating its 10th anniversary and on the verge of hiring its first paid executive director.

In addition to providing resources and support for faith institutions to launch their own earth care efforts, Hope for Creation is also involved in civic environmental efforts. HforC members spoke on behalf of the City of Kalamazoo when it passed its climate crisis ordinance, says Rev. Ruth Moerdyk, HforC Interim Coordinator and Pastor at Skyridge Church of the Brethren. Three of HforC’s members are in the 15-member council advising the City’s Sustainability Coordinator.

“In the best of all worlds, faith-based institutions and people of spirit recognize how interconnected everything is. And how important it is to practice compassion,” says Moerdyk. “There’s things you can agree on and you don’t have to agree on everything. That’s what a coalition or group operating together is. Some people want to chain themselves to fences and other people want to write letters. We need it all.”

Faith institutions also influence each other, says Shattuck. In Kalamazoo, Temple B’Nai Israel won an award from Interfaith Power and Light, a national leader in engaging communities in environmental stewardship and climate action, for being one of the first congregations to put in electric vehicle chargers. Other congregations, such as St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, have also added charging stations. People’s Church, which has an ambitious goal to be net zero by 2030, won an IPL award for its sustainability planning.

Michigan IPL also awarded a Sacred Spaces grant for energy efficiency to Kalamazoo’s Allen Chapel AME which allows them to save money to put towards other missions of the church.

“The churches are learning from each other. Westminster (Presbyterian) put in solar panels, and so People’s (Unitarian) put in solar panels. There was this great synergy. Hey, the Presbyterians and the Unitarians are working together It just gives you hope in a time when we think we’re all in our own little tribes.”

Editor’s Note: As part of this series, we will be offering suggested reading, as well as resources for engaging in local, statewide, national, and global climate care efforts:

RESOURCES:

Kalamazoo Earth Day. Earth Day is Monday, April 22, but events are ongoing and begin with an Earth Week kickoff March and Rally for Climate Justice at 3 p.m. Friday, April 19 in Bronson Park. For a comprehensive schedule of local Earth Week events, see this LINK.

Kalamazoo Nature Center Earth Day activities, including information on a Kalamazoo River cleanup (registration required).

How Faith Communities Can Help With Climate Change, Earth.org

The Climate Optimist, a Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health newsletter on the good news regarding climate change, what we can do, and reasons to have hope.

Kalamazoo Climate Crisis Coalition, a local group that “mobilizes collective action to achieve immediate and drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and rapid adoption of renewable energy through a transition grounded in social, racial, economic, and environmental justice”

Climate Change Statements from World Religions

Earth Day Prayers from many faith traditions, gathered by Interfaith Power and Light

SUGGESTED READING:

“Not too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility”, an essay collection edited by Rebecca Solnit and Thelma Young Lutunatabua

“Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Wall Kimmerer

“Faith, Hope, and Sustainability: The Greening of US Faith Communities” by Cybelle Shattuck

Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World, Katherine Hayhoe

Taylor Scamehorn (she/her) of Kalamazoo is a multidisciplinary artist with a BFA from Kendall College of Art and Design. She freelances for Southwest Michigan’s Second Wave Media as a photographer and editorial artist and is a member of the faculty at the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts. She specializes in work driven by concept and narrative, focuses on her sustainability practice, and enjoys spending time in nature.