Calhoun County creates Public Defender Office so everyone can have experienced, capable defense

When low-income people do not have high-quality legal representation they will be imprisoned more than they should be and ultimately their civil rights will be denied. To address such injustice, Calhoun County has created a Public Defenders Office.

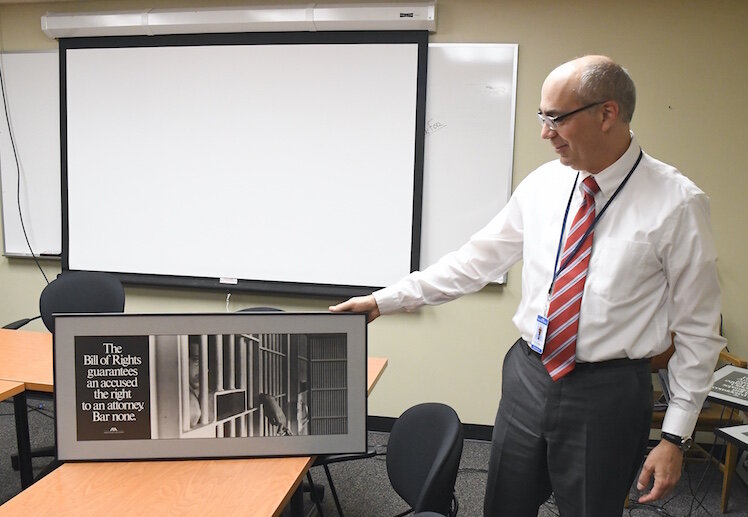

Joe Eldred was ready to wind down his private legal practice, but he wasn’t ready to stop practicing law.

Eldred is one of eight attorneys who have signed on to work for Calhoun County’s Public Defender Office which began providing legal representation in September to county residents who are not able to afford an attorney.

After running his own law office for 27 years, Eldred says in his new role as an Assistant Public Defender he’s hoping to ensure that people in Calhoun County who need quality defense work will get it.

“I think a lot of people slipped through the cracks and now there’s somebody there to give them advice and explain to them how to proceed with their case,” Eldred says. “I like to do trial work and this will give me an opportunity to do that.”

The creation of the Public Defender Office began in March with the hiring of David Makled as the county’s Chief Public Defender. The establishment of the office is the result of recommendations from the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission, created in 2013 by then-Gov. Richard Snyder to address growing disparities in Michigan’s legal system as it pertained to those who couldn’t afford adequate representation.

“About 10 years ago there was a lawsuit and a movement nationwide to reform the system,” Makled says. “The systems set up were inadequate and under-resourced and justice was not being served. Michigan was ranked 44 out of 50 states for resources and funding for indigent defense based on a study that was done.”

The American Civil Liberties Union maintains that people of color disproportionately suffer the consequences of a legal system that is unable to provide them with a quality, adequate defense.

“America warehouses over two million people behind bars. If low-income people caught in the carceral (prison) system do not have zealous advocates, they will continue to be over criminalized, over incarcerated, and deprived of their rights,” says an article published in May by attorneys for the ACLU. “Without functioning public defense systems, we cannot meaningfully reduce the staggering number of people held in pretrial detention, wrongful convictions, or abusive prosecutorial practices.”

The Michigan Indigent Defense Commission proposed standards for work with those who use a public defender, including the use of investigators and experts and the presence of legal counsel at first appearance and other critical stages of criminal proceedings. The commission also stated that each county could select its desired indigent defense delivery method to comply with the MIDC standards, and multiple models ranging from a defender office, an assigned counsel list, contract attorneys, or a mix of systems could be offered.

“Most folks who need a public defender obviously are not the movers and shakers of the world,” Makled says. “They don’t tend to have good jobs and often have mental health or substance abuse problems and are not able to advocate for themselves very well. Unless society as a whole is willing to look out for them, they can fall through the cracks. If we as a society don’t look out for these people, who will?”

The attorneys who have been hired in Calhoun County’s Public Defender Office are passionate about working within this new indigent defense system, Makled says, adding that they could have chosen a career in private practice or sought work outside of Calhoun County. He acknowledges that those who are coming to work with him are “taking a bit of a chance.”

What he anticipates is that his full-time attorneys are going to develop a real depth of ability and experience as time goes on.

“My vision for this office is to really be a community resource,” Makled says. “We want to get involved in community programs and be involved with other agencies to figure out what leads people to do the kinds of things that drive them to our office for legal help.”

County Administrator Kelli Scott says she hopes that residents of the county will view the establishment of the Public Defender Office as a commitment to offering the best justice system possible.

She says the public defender office model adopted by the county is the most popular, especially for counties the size of Calhoun and larger. Previously, the county has always provided attorneys through the court system to people who can’t afford them. Judges assigned cases to individual contract attorneys who were paid a fixed amount for each case.

“One of the main goals is to create oversight independent from judges who shouldn’t be involved in assigning cases, deciding who gets what attorney, and how much they should get paid,” Scott says. “If these attorneys are going to represent defendants and the attorneys are assigned by judges deciding the cases there is the potential for the appearance of a conflict of interest.

“There shouldn’t be any appearance of a conflict of interest because if they issue a verdict, someone could argue that the defendant didn’t receive a fair defense.”

By addressing barriers such as the lack of access to resources like independent investigators, adequate space to have confidential meetings, and funding to put into these areas the Public Defender Office will benefit the whole system, Scott says.

The county’s budget for the provision of indigent defense has gone from $700,000 annually to $2.5 million. Scott says this increase covers the cost of expenses such as building renovations, the addition of staff investigators and software that will create more efficiencies and less paper waste.

The state of Michigan is providing an additional $84 million divided among its 83 counties for indigent defense work. And Makled says grants from the state will make up the difference between the $700,000 annually that the county had been budgeting for public defenders and the new $2.5 million budget. He has approval to hire 12 attorneys, a number of investigators and support personnel to staff the office.

About 75 percent of the office’s total caseload will be handled by attorneys working for the Public Defender Office. The remainder will be assigned to outside, contract attorneys who are currently active with the Bar Association.

Eldred says as a contract attorney under the old system he took on a few misdemeanor cases, but he stopped because it wasn’t as lucrative as the civil and family matters work he was doing as a solo practitioner.

“Money does make a difference in the sense that when you pay for it you have an attorney who can devote the time needed,” Makled says. “The idea for this new system is to eliminate that as much as possible.”

Eldred says the caseload he has as an assistant public defender is different from the cases he took on as a solo practitioner.

“It’s a lot of felony stuff. It’s not all murder cases,” he says. “A lot of it is just going to court to meet with judge and prosecutor and fashion a resolution everyone can agree on. A lot of cases will get resolved before they go to trial.”

Eldred had been assigned more than 74 cases when he was interviewed for this story. He says people come in for an arraignment and he is able to explain to them about the process and next steps.

“There is an uptick in the number of people getting attorneys appointed by the Public Defender Office because of that,” Eldred says. “This is all so new. I’m trying to sort out exactly how many cases I will have.”

According to the standards set by the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission, each attorney should handle no more than 150 felonies per year, or 400 misdemeanors, or essentially a prorated amount between the two.

“Right now we’re a bit understaffed and above that mark,” Makled says. “There are about 1,600 new felony filings every year and about 6,500 misdemeanors. We just handle adult criminal cases so juvenile matters are still handled under the previous system.”

In general, Markled says, “The vast majority of the felonies have court-appointed attorneys and a few have privately retained attorneys. As far as the misdemeanors go, not all misdemeanors qualify for a court-appointed attorney. It depends on the incident and whether they are likely to receive jail time. Most of these are minor misdemeanors or ordinance violations. However, judges have discretion at any point at any time to have our office involved.”

The court appoints cases to the Public Defender Office, which assigns cases to its attorneys and makes decisions about the need for the involvement of investigators and experts. Prior to the establishment of the PDO, attorneys had to petition the court to provide investigators and experts.

“Previously the courts appointed attorneys and decided whether they were entitled to an investigator or expert and under our new system or office makes those decisions,” Makled says.

Makled says it’s not his office’s job to “play tricks or get people off on technicalities.” He says the money that is being spent will benefit everyone involved in the judicial system.

“Our justice system works best,” Makled says, “when both sides have experienced, capable attorneys who have the necessary resources and when that happens you end up with the fairest and just results so you don’t have people falling through the cracks. It means you’re going to have fair representation.”

Photos by John Grap of John Grap Photography. His work is featured here.