CommuniTeen read in Portage tackles complicated issues of criminal justice system, race, and gender

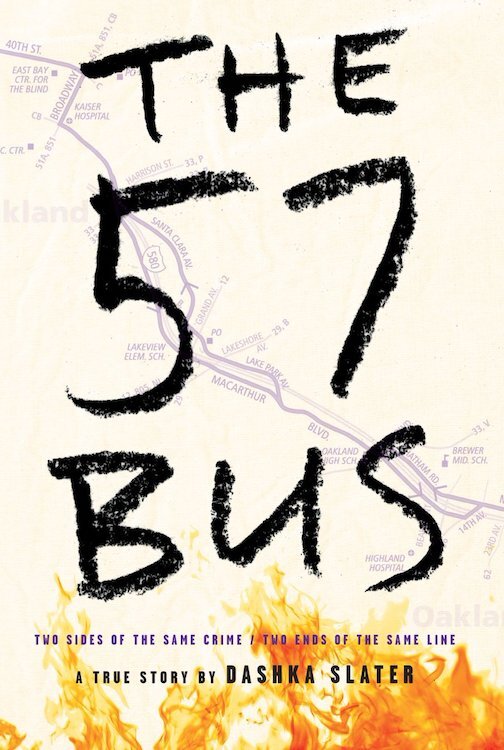

Journalist and author Dashka Slater’s “The 57 Bus: A True Story of Two Teenagers and the Crime That Changed Their Lives,” is young adult nonfiction that examines complicated issues.

Slater is the 2022 Portage CommuniTeen author. Teens and their community have been reading “The 57 Bus” in preparation for her March 12 Portage Northern High School visit.

The book centers on a 2013 incident on a bus. A Black 16-year-old, Richard Thomas, egged on by his peers, used a lighter to set the skirt of non-binary 18-year-old Sasha Fleischman on fire. It resulted in third-degree burns and multiple operations for Fleischman, and hate-crime felony charges for Thomas.

Gender identity, race, the justice system, the concept of hate crimes — the work explores complex issues, issues that are controversial depending on one’s social/political leanings. It’s not too surprising that during the recent spate of book challenges, which seem to focus on books covering race and gender issues, there’ve been calls to remove “57 Bus” from high school libraries.

(Both this year’s CommuniTeen book, and last year’s “All American Boys” were challenged in Tennessee schools recently. (Recent book removals in Tennessee schools intensifies, paywall)

“Obviously writers and journalists don’t like seeing books being banned. It runs against our fundamental values,” Slater says from her home in Oakland, Calif.

“This movement is extremely dangerous to the fundamental principles of our democracy,” Slater says, “which is that we can work out the policies that benefit us as a society through an open airing and discussion of the issues. If you can’t read about them, you can’t talk about them, and you can’t think about them, and you can’t come to any common understanding on how to approach them.”

She says, “I believe so much in the power of discussion and conversation about controversial topics, and have seen with ‘The 57 Bus’ how much good comes from just having respectful discussions of things that are sometimes hard to talk about, like race, and gender, and justice.”

Right after the book was published, she got her favorite letter from a young reader, “a White boy from a suburb, and he wrote four pages of extremely heartfelt musings in response to the book. He was trying to figure out where he stood with things.”

He wrote, “If I were on the bus with Sasha, and if I was alone, I would’ve left them alone. But if I had been with one or two of my friends, we probably would’ve done something to mess with Sasha.”

Slater says, “It wasn’t until reading the book that the kid was able to put himself in the shoes of the person who, his first take was, ‘That’s weird. Why are you in a skirt?’ That’s the power of what we do, when we write about difficult topics, is that we allow kids to get inside somebody else’s perspective.”

A neighborhood incident

“It was all very local, and because of that, very personal,” Slater says of the story that, as an intriguing event for a journalist, got its hooks into her.

She lived near Thomas’ high school. “The 57 bus was the bus my own kid used to take to his public high school.”

After the news broke, Slater followed the discussions, and the emotions, from neighbors and online forums. “After Richard was arrested and charged as an adult, and faced an extremely long prison sentence, my criminal justice reporter alert came on, and I started thinking, Why is that? How should we think about hate crimes that are committed by juveniles like that?”

She interviewed both families and dove deep into the story. The New York Times Magazine published her resulting work.

It’s a complicated account, not easy to distill into contextless hot takes and tweets.

“Our world is very much attached to easy answers and soundbites and hot takes. Unfortunately, that approach to life misses… that people are complicated, situations are confusing, sometimes two values that you hold can feel like they’re in opposition to one another. Certainly they did for me at the beginning, which is one of the reasons I was interested in this story,” she says.

“It felt like, if I was going to be an advocate or supporter of them (Fleischman), then that meant I had to be an adversary to this kid who had committed this crime. Or, that if I was going to be an advocate for Black youth or juveniles who are system-involved, then that meant that I had to minimalize what had happened to Sasha. And struggling with how to do both, and how to hold both of their stories at the same time, to me, is kind of the entry into having a world view that allows for different people’s experiences, and maybe get to a more-humane approach to criminal justice.”

We assume that a crime becomes a hate crime when the victim is attacked because, to the perpetrator, they represent a minority in race, ethnicity, religion, gender — so a greater punishment is needed because the crime was also against the victim’s civil rights. It’s not just an attack on an individual, it’s an attack on a group. Isn’t that the case in situations like this?

Slater replies, “What we run into are the limits of the criminal justice system. We have this impulse as a society to solve every problem with the criminal justice system. If there’s something we don’t like, let’s criminalize it. Which goes back to the earlier book-banning discussion,” Slater says with a laugh.

“The criminal justice system is a very blunt instrument, and it isn’t really designed to solve social problems. Criminalizing things makes us feel good because we’ve now taken a stance and said, ‘I’m against it, this is wrong and it shouldn’t happen.’ Which is legitimate. Hate crimes are wrong and shouldn’t happen. But… the key question is what actually solves the problem? And unfortunately, there’s very little evidence the criminal justice system solves any problem.”

Other news accounts showed that Thomas had regret over what he’d done — Fleischman’s father said the family was “moved to tears” by letters from Thomas taking responsibility for his actions. Thomas faced a sentence of seven years, which meant he’d eventually be moved from a juvenile facility into a prison with adults, and be in his mid-20s when released. He pleaded no contest to the assault charge, the hate crime enhancement was dismissed, and Thomas’ sentence was reduced to five years.

Journalistic nonfiction for teens

How does one turn complex long-form journalism into a book that teens would read?

“I actually had no idea it was even permissible!” she says. “When I was writing the story for the Times Magazine, I thought this would be a topic that young people would really love to discuss. Is it even a thing, narrative nonfiction/long-form journalism for young adults?”

She has also written a few children’s picture books, on less-heavy topics such as a French snail named “Escargot”. “Happily, my editor (for the picture book) knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

“I knew the kids could understand all the issues, and they could understand if I could explain it well, the legal technicalities and so forth. But they needed to be emotionally engaged. And to be emotionally engaged I had to tell it much more novelistically and to be in the perspectives of the different characters, and really talk about what it was like to be each of these kids, who their friends were, what their schools were like, what was on their minds, what brought them up to that moment on the 57 bus, and what happened to them afterwards.”

She did a second round of reporting and interviews, gathered more details. Readers told her the result “reads like a novel,” Slater says. “With enough reporting, you can make it feel like a novel by having all those details there.”

Facilitating conversation

Again, Slater says that though controversial to some parents, books like hers are needed to help young readers think about, and talk about, tough issues, to “facilitate conversation.”

Slater has received “so many incredible letters from young people. A lot from kids who are gender-non-conforming, trans, non-binary. Or kids who’re gay. In situations where they might not be safe to be out, they can’t tell their families, or they are unable to be out at school, they’re harassed at school. Or they’re out at school and feel super comfortable and accepted,” she says.

“A trans girl wrote me very recently about being harassed on the bus, and having some boys steal her diary and write terrible things in it, and she reported them. She ended up getting apologies from at least one of the boys.” The letter highlighted “that moment of courage when she realized she wasn’t going to allow this to happen.”

Some readers ask for advice. “‘My friend is a lesbian, and my mom won’t let me see her because mom thinks now she’s not safe to be around. How do I talk to my mom?’ Lots of letters from kids who may not identify with Sasha or Richard, but who just felt interested and related to one or both of the kids in some way that surprised them and made them start thinking about the issues of race and gender.”

“One of the things that I really love is when kids or parents tell me that my book is a way that they had a conversation that they needed to have.” Some readers give “57 Bus” to their parents, because “they’re non-binary, and want their parents to understand.”

Other letters tell her, “‘I never read about kids like me, I’m a kid like Richard, or I have a friend like Richard.’ Kids in juvenile halls sometimes write to me and say, ‘I’ve never seen somebody like me portrayed sympathetically before.’ Those are really moving letters to receive as well, because these are kids who have so much shame about the fact that they’re involved in the criminal justice system, incarcerated.”

Slater hopes incarcerated youth can take to heart the message that “their entire being cannot be summed up in the fact that they committed a crime.”

Convicted teens are at risk of dropping out of high school, and of never leaving the criminal justice system, she says. “There’s this feeling that now your fate is determined, and whatever you do you’re going to end up back there.”

She hopes to help “people know a little bit more about these kids, to be reminded that they are actually just kids — 16 is extremely young, 18 is extremely young.” At that age, she says, there is still a “capacity for change.”

_____________________________________________________________

2022 Portage CommuniTeen reading project

Tuesday, March 15, 6:30 p.m.: Dashka Slater, 2022 Portage CommuniTeen Author, will be at Portage Northern High School. More information here.