Editor’s Note: This story is part of our series, Sacred Earth which examines the intersection between climate change — and faith, worldview, philosophy, psychology, and the creative arts. This series is sponsored by the Fetzer Institute. o see more photos of Solfed Farms, please scroll the carousel above.

When you’re living a “low-frequency” life, a certain peacefulness becomes vivid.

Just north of Kalamazoo, in Cooper Township, there’s a family building a straw bale house, powered by the sun. They’re on a farm with beds of fruits and vegetables, bee hives, a goat pen, and a chicken coop, that’s all very quiet.

A couple of hens at Solfed Farm

We hear distant calls of sandhill cranes on a sunny October morning. The farm’s rooster crows, the loudest noise around, like it just had to disturb the peace.

A German Shepard mix whines, wanting attention.

Larissa Touloupas let Dasha off her leash to greet the visitors.

“Dasha! Sadni!” she tells her. That’s Slovak, meaning “sit!” “She speaks another language,” Touloupas says.

The area is not quiet enough on Solfed Farms, Touloupas feels.

Larissa Touloupas, co-owner of Solfed Farms, with dog Dasha.

“I grew up even more rural than this,” down near Leonidas, she says. “When I hear the highway I’m like —” she makes an angry face. The farm is less than a mile from 131. “You can’t hear it too bad right now, but usually it’s raging.”

She casually picks sap from a cherry tree, and eats it, “like gum.” There are pines on the property with sap she can make soap out of, Touloupas says, She picks raspberries from the vines, and eats them — “I think I ate a stink bug,” she says, sounding not too concerned. She spits it out.

There are hazards in farm life, but many rewards.

Ondrej Pekarovic, co-owner of Solfed Farms, is esearch engineer at Western Michigan University’s Department of Civil and Construction Engineering.

Her husband Ondrej Pekarovic was working on something, somewhere on the farm, she says. They have two kids, five and six, who were at a babysitter’s. “We take the childcare when we can so we can focus on building,” she says.

“They love this life,” she says of their children. “Every day we walk through the woods to go and milk our goats and pick up the eggs, and they play on the hay bales. It’s always an adventure for them here.”

Do you know how Brussels sprouts grow? Solfed sells its produce, but also serves as a a farm education center.

The kids’ room is a spacious loft that also serves as their homeschool classroom — but they also have music classes at their nearby grandparents’ piano, and sewing classes at Touloupas’ sister’s house, also a walk away.

Scenes from Solfed Farms

The family has 24 acres. It’s a five-minute walk to the woods and Larissa’s in-laws, where Ondrej grew up. He was young when his family immigrated from Slovakia to Michigan farmland.

As teens, he and his brother planted oaks, pines, and spruces on ten acres of the land Pekarovic and Touloupas now own. The land used to be owned by a farmer who was enrolled in the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program, which pays farmers to turn portions of their fields back to nature.

Off the grid and living in straw

We found Pekarovic inside, working on their straw bale house. It’s a house literally made of straw bales, covered with stucco that’s a mix of earth and clay from their land, kaolin clay, sand, toilet paper, and cattail fiber. Exposed cut wood beams and 60-year-old white pine logs help hold it up.

Withstands huffing and puffing

If anyone’s tempted to make any Three Little Pigs reference, know that Pekarovic is a research engineer at Western Michigan University’s Department of Civil and Construction Engineering. One of his specialties is the study of the forces of earthquakes and hurricanes on structures, so there’s likely no Big Bad Wolf threat to his straw house.

Larissa Touloupas and husband Ondrej Pekarovic have worked hard to bring t life their vision of Solfed Farms.

Of his summers planting trees, Pekarovic says, “This was back in high school, and it was a summer job,” he says “I always cared about the trees and foresting. We camped out here a lot and I really like this spot… it’s on top of the hill, you can see everywhere.”

The night before the interview, he’d slept outside in a hammock during the unusually warm October night.

The farm is truly off the grid. They have a couple of solar panels for electricity. They have an e-bike as a second car, that Pekarovic often uses to commute to WMU. But Touloupas says they do have a gas-powered car and a farm truck.

Scenes from Solfed Farms

“I’m not a purist, and I also don’t believe that everyone can live this way,” she says. She’s not sure “that it’s even sustainable or feasible, especially with solar.” They hope to get a windmill for electricity someday, she says.

Skilled friends volunteer labor. “We’d have these big stucco parties, and I would just pray that it would be sunny because we needed it to run the cement mixer (powered by solar). It would be sunny, and then we would use it, and then as soon as we were finished the power would cut out and I’d be washing myself in the rain barrel, you know,” she says with a laugh.

“Low-frequency lifestyle”

Building and planting all this wasn’t easy, was it?

olfed’s straw bale house is still a work in progress. The family hopes to move in for real by winter.

“Oh my god. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my entire life. Harder than birthing children,” Touloupas says.

“I didn’t,” she says, laughing, “see another option! I was definitely raised with the mentality of do it yourself, and you can do it, and we need to create a sustainable future.”

She adds with a long, thoughtful pause, interrupted by the rooster crowing, “I did it because… I saw no other way.”

An interior view of the straw bale house at Solfed Farms

Pekarovic bought the land ten years ago. They put in a driveway, put in a well, built a barn. It took five years to build the house. “And in part, it took that long because we’re paying for it as we go. We didn’t take any loans. Then, just the process of straw bale building is really labor intensive.”

The house is not quite finished. At the moment, part of it is packed with kitchen components that they’re working to install. The family hopes to move in for real this winter.

The winding staircase inside the home which is a work in progress.

Not everyone can create and live in an off-the-grid home made of straw, she knows. But, “I think you can do it with minimum inputs if you’re creative and if you’re willing to be uncomfortable. We are so addicted to comfort,” as a society, she says.

But, why do this, make this home and farm from scratch?

“It was really a collaboration of the universe gifting us the supplies and materials we needed, and giving us the energy and the capacity to do it, mixed with the deep desire to live what I call a low-frequency lifestyle, where the amount of inputs are low, and so the amount of money and resources that you use can be low. Therefore, you don’t need a lot of money,” she says.

“Obviously, we had a lot of resources and we had a lot of privilege to be able to obtain something like this. To obtain land to do something like this.”

However, it’s a fact of life that “either you do the labor yourself or you outsource it to someone else.”

A greenhouse at Solfed Farms

She thinks of how traditional construction happens. “You know people who work in drywall factories are not being exposed to a good environment. So we’d rather try to find healthy ways to do that ourselves.”

The land was bought with cash. “My husband was able to do that because he lived with his parents, and saved all his money.”

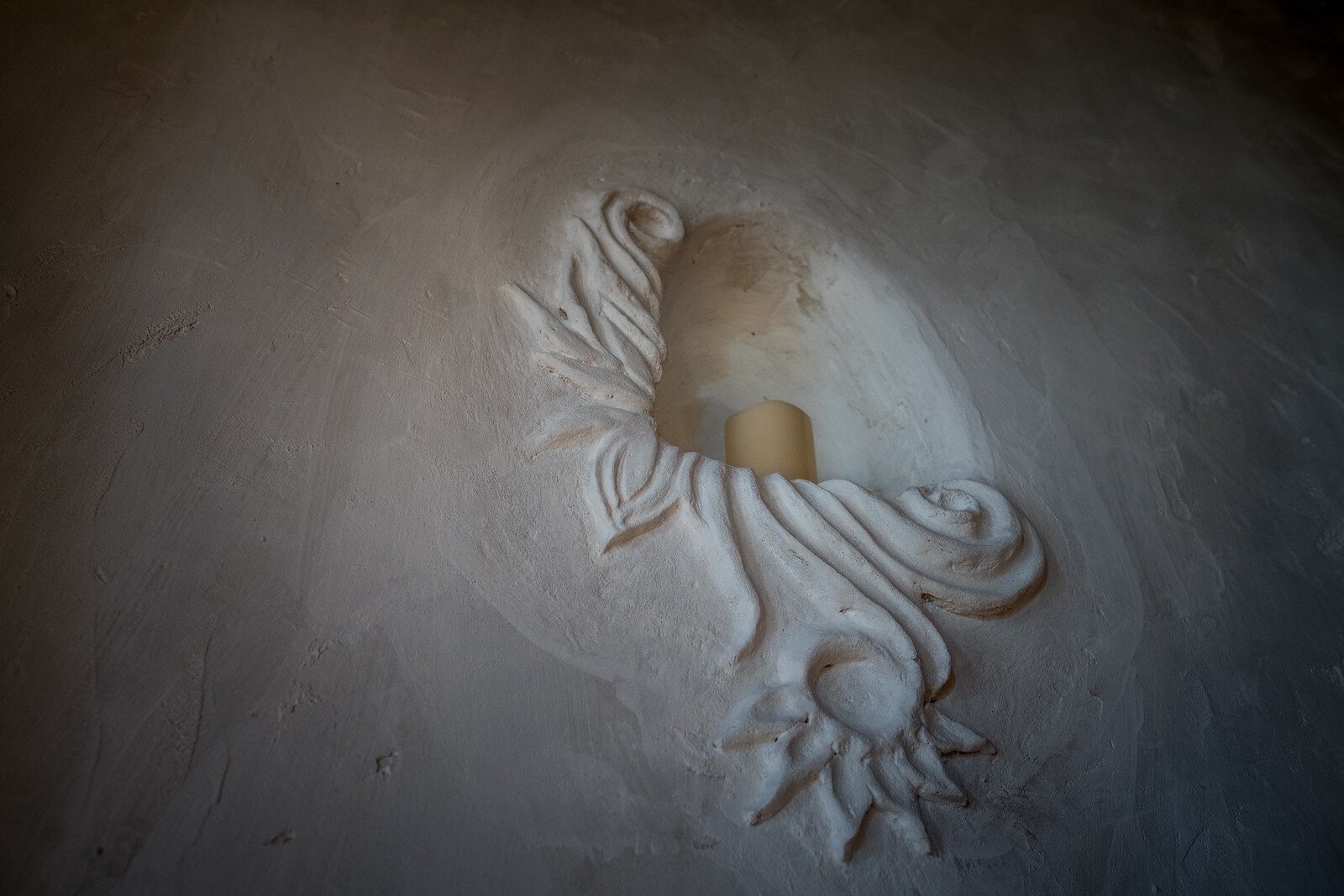

Decorative elements in the straw bale house at Solfed Farms

They have no mortgage, no electrical bill, no gas bill, “we just keep things really simple.”

They turned to recycled and salvaged items. One of the first buildings on the farm is a barn with salvaged pallet wood. “We had to pry apart the pallets and pull out all the nails,” she says.

The unfinished pine timbers inside the house were a cheap $10 a piece. The fanciest part of the structure, a perfect spiral wood staircase that would’ve been $7,000 new, they found for $1,000.

Larissa Touloupas and her husband Ondrej Pekarovic and their children enjoy the many animals of Solfed Farms.

“The first five or six summers that we lived here we lived in an RV that we got for free on the side of the road — so like that’s what I mean by the universe gave us the tools we needed to do this,” she says.

At times it seems like the universe isn’t going along with their plan.

When one is “working with nature, sometimes it feels like you’re combating nature,” Touloupas says.

Larissa Touloupas enjoys sharing homestead life when her children.

“Being a farmer especially, there are times where it feels just like everything’s going against you, you have moles undermining your crops and deer eating your other crops and rabbits ripping through stuff. Big storms come through and you have to contend with hail damage.”

“It’s very spiritual in the sense that sometimes you really just have to let go. Last year I gave myself so much gray hair worrying about underground burrowing creatures. They destroyed thousands of dollars of crops. But what can you do, you know, you just have to keep going, I guess.”

“It’s not a mystery what daddy does.”

Pekarovic’s engineer side speaks of R-value versus thermal inertia (R-value is the industry’s measure of a wall’s insulation ability, but the straw bales covered with their clay mixture have a high thermal inertia, meaning it retains its temperature longer).

Scenes from Solfed Farms

What would a 300-pound section of wall on a regular house, is 3,000 pounds for their house. He’s thought about what would happen if a tornado hit — “might be a formidable challenge” because of hurled projectiles, but with the house’s round design, straight-line hurricane-force winds might be no problem.

It’s a matter of engineering and construction, but he also sees the house as an art project. “If you like unique things, I mean, nothing like this exists in Kalamazoo County, so we had to create it for ourselves “

Before building their straw bale house, Touloupas and Pekarovic built this open-air kitchen as a test of the method. “This gets a ton of weather exposure,” Touloupas says. “We’ve never had any issue with moisture or anything.”

But it seems like there’s more behind doing this instead of hiring a bunch of contractors to build the usual house.

“Philosophically, what motivates one to live this way comes from the Gospel, you know, like ‘sell all your belongings and follow me,'” he says.

A simple life — as he also puts it, on “a lower frequency” — for him and his family, is his goal.

“I mean, if you have children, how can you do that? But on the other side, you’re climbing the corporate ladder. There’s something in between, where you can live on a lower frequency… You can have a part-time job, you can be around your own children.”

“

It’s not a mystery what daddy does, he’s building a house… It was always a mystery what my father was doing, he was somewhere in some lab.”

Pekarovic speaks about when he was younger, doing bicycle tours out West, nearly freezing on desert nights. Back then, he didn’t have kids.

“It’s not like you can do a whole lot of adventures when the children are so young, so this is one thing that we can do with them.”

There’s also some freedom in what he and his wife are doing, he says. “You know freedom and adventure is an antidote to depression, you know, so it’s like this is adventurous, having an adventurous life.”

No one farms to get rich

Not everyone can do all this, Touloupas says, but “they can do small things… You can start small, put up a few solar panels, plant some fruit trees. Maybe you want to build a little naturally built woodshed or build your own greenhouse. Anything anything you can do is going to help “

Scenes from Solfed Farms

She’s been educating children on the simple joys, and struggles, of farming.

Touloupas runs their “farm school” program, where kids come out once a week, June to September. Each student gets a garden plot, some donated seeds, and seedlings and is guided through a season of growing things. She’d like to make the farm a spot for education. “I’d like to become a nonprofit,” she says.

“Teaching through experiential learning is really the best method,” she says.”This kid just planted one whole handful of corn.” She points out a clump of stunted corn stalks. The child learned an important lesson — corn needs space to grow.

Larissa Touloupas of Solfed Farms living a “low-frequency lifestyle.”

“I think the greatest teacher is them just seeing what happens. ‘Where’s all my corn? There’s no corn, why is there no corn!’ And then we talk about it.”

Students learn about plant life cycles, soil health, seedlings, and photosynthesis, “sometimes we teach fire building or natural primitive skills. We have a beekeeper come and do a demonstration. This year they made herbal first aid kits.”

Parents can get involved, “they get to experience digging potatoes for the first time in their life, or learning that a pepper turns from green to orange — they never knew that! Or how corn grows.”

As a farm, Solfed operates as a CSA (community-supported agriculture) outlet that sells produce directly to customers. “Once a week people come out here, and they pick up a share of produce.”

Pekarovic had slept outside in a hammock the night before. He grew up next to the field Solfed sits on now, and often camped in the same spot as a teen.

Long-time farm families will say that you don’t go into farming to become rich. “But it’d be nice to at least have enough money to cover all my costs and my time, and, like, pay myself something instead of just paying myself nothing.”

But she gets rewarded in other ways.

Scenes from Solfed Farms which is a Community Service Agricultural farm.

“I feel that the universe gifted us all of these resources and gifts and energy to be able to do this,” Touloupas says. “Every day I wake up and I come outside and I feel so blessed to be able to see greenery and hear the sounds of the birds, and see turkeys flying away, and deer frolicking.”

Contact Solfed Farms through Instagram and Solfedfarms@gmail.com.

Want to build your own straw bale house? See a video on straw bale building from the University of Michigan.