African American Vernacular English, Appalachian English, Chicano, and Spanglish are all part of the class this year.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

As a child, Jill Anderson says she would hear Black classmates speaking English in a way that she considered not proper. Anderson says she now knows that her reaction to the way her Black classmates were speaking was racist.

Through overhearing the lessons being taught in her son George’s virtual classes, she discovered that what she heard as a child is African American Vernacular English. It is among the focus areas of a 10-week unit on Communications offered at the Battle Creek Public Schools STEM Middle School.

As a “white, suburban person” who is on a journey to becoming anti-racist, Anderson says she thinks the intentional inclusion of an AAVE curriculum serves as an equalizer with younger generations.

“I don’t think there was an awareness in the past,” she says of her time as a student. “I think now, especially in this era of George Floyd and everyone’s focus on racial issues is a great time for this to be happening in our schools. This is a really important tool for children to be able to learn about African American Vernacular English. … Teaching this in schools is a way for students to learn that this is a variation of the English language which is legitimate and good.”

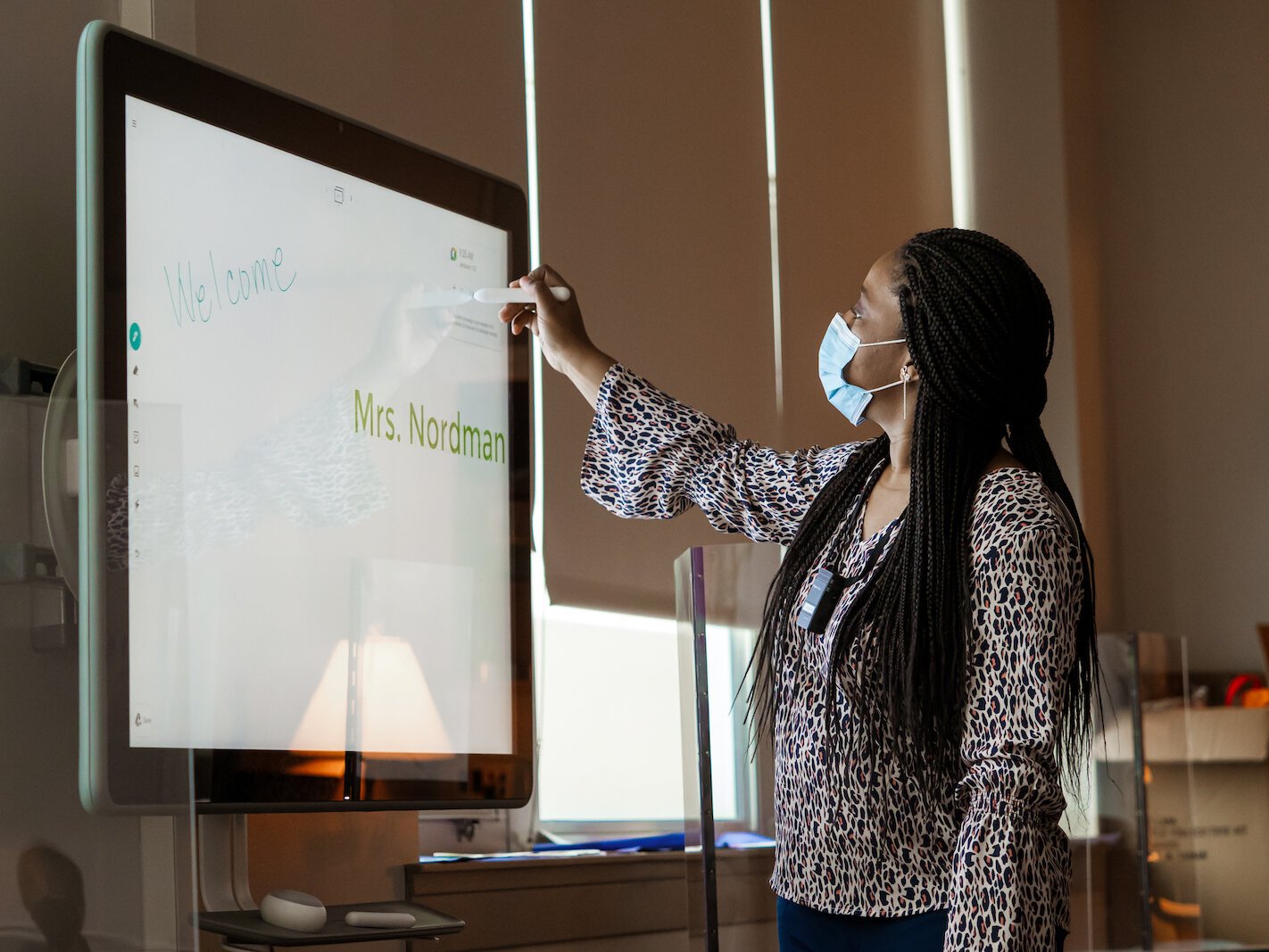

The focus on AAVE was part of a lesson plan created by Jamesia Nordman, who teaches 6th and 7th grade English Language Arts at the STEM Middle School. In addition to AAVE, students also learned about Appalachian English, Chicano, and Spanglish, all dialects not immediately recognized as widely as Standard American English.

During last year’s Communications unit, Nordman’s students learned about ancient languages and cultures that included hieroglyphics, the Mayan language, Chinese poetry, and communicating within Confucianism. This year, she says she wanted to take it in a more modern direction for a few very important reasons.

“I wanted to communicate to the kids that people may communicate differently and that it’s OK,” Nordman says. “I wanted them to understand and try to develop empathy for others. Many times if people are not like you you dismiss them. But African American, Burmese, and Latinx is our population. We’re highlighting differences, but we’re all Americans. Spanish, Chicano, and AAVE have become mainstream and that’s what unites us as Americans.”

Anderson says Nordman is providing an incredible tool.

“That schools are giving legitimacy to AAVE signals to people who don’t speak that as their regular vernacular that it’s OK and different is good,” she says.

Part of the learning process involved explanations of the different languages and why certain phrases are considered commonplace. For example, the Chicano dialect is very paternalistic in the culture and “Hey Bro” is used frequently. Addressing everyone as “Girl” is a term of endearment, not just in AAVE, but in many cultures.

Often, children for whom Standard American English is not the primary dialect spoken at home or with their friends use code-switching, which means they will navigate between the dialect they were born and raised with and Standard American English, which until recently has been the more recognized and accepted. This is true, not just for Black kids who speak African American Vernacular English, but also for those who are fluent in Spanglish and Chicano.

Teacher Jamesia Nordman says she wants to empower all children and help them with the code switch.

“They can use AAVE when they’re talking with their friends, but code-switching is a skill they need to acquire. They can’t speak the same ways to their friends as their co-workers because the business world still operates predominantly with SAE,” she says.

“They need to master SAE as well as keeping the connection to their roots. It helps to retain their cultural identity and maintain their American heritage as well. You’ve got to know the rules to speak all of these languages correctly.”

George says he understands the language of AAVE and where it comes from and what changes from SAE, but he doesn’t really get the rules for AAVE because the rules for SAE, the language he has been brought up with, are different.

“I’m not very sure of the rules,” he says. “We go fast and don’t have much time to write things down and take notes.”

This was among the challenges for George of learning about these languages in a virtual setting. Nordman says it would have been better for her and her students to be in an in-person classroom setting for this unit. She says cameras and microphones were sometimes off so she couldn’t hear her students speaking. In a face-to-face setting, she is able to walk around and listen.

The online setting presented other obstacles, including the ability to successfully translate, which on its own is difficult enough. Lessons in grammar only heightened the difficulty for students who were learning about past, present, future, and occasional tenses, and subjects and predicates. Nordman says teaching grammar is no longer an imperative.

“Learning that grammar is difficult for a generation of kids who didn’t have exposure to grammar. They write the way they text,” she says. “Translating was challenging as well because they’re so used to being able to go to Google Translate. You can’t do that for this. You’ve got to feel it. They didn’t want to mess up. They wanted to be perfect at it. I just want them to embrace it.”

From a practical and worldview standpoint, she wants them to know that being a linguist is a viable career option and people make good money doing it.

“English is a viable field. I always want to make the connection about what they’re learning in school and what their future could be,” Nordman says.

A Necessary Tool to End Racism

George says he thinks learning about AAVE and the other languages will help people to better understand and appreciate those who don’t look or speak like them.

“I would like to know more history about how African Americans speak and why they act a bit differently than white people. I think it’s because they’ve had a very rough path with white people and so they feel differently about a lot of things,” he says. “A few kids in my class don’t treat other kids the way they treat African American kids. It makes it a bit harder to learn about them when some people are treating them like friends and others aren’t because they kind of stay with the kids who like them.”

His teacher Nordman says, “I think for our African American students they are oftentimes ridiculed for how they speak. If they speak AAVE, they are considered unintelligent and if they speak SAE they are considered particularly articulate. People will say, ‘Wow, you talk White.’ When they code-switch it doesn’t mean that they’re unintelligent and I don’t want kids to stigmatize each other,” Nordman says. “I want people to feel more comfortable in their skin. I don’t want them to feel awkward. I want all of our kids to get along with one another. If they hear someone speaking a different language, I want them to be OK with that.”

L.E. Johnson, who works with the African American Collaborative and the Southwest Michigan Urban League, says, “We were taught that talking White means that you’re educated and talking Black means that you’re ignorant. When I was in school there was no way in heaven that I was allowed to use AAVE. The dominant culture was (Standard) American English and we were taught that anything other than that which was not English wasn’t beautiful.”

Nordman says she had a similar experience during her time as a student at a STEM high school in Detroit. While there she took a college-level English course focused on the classics and SAE. She says there was a little Maya Angelou interspersed in the lessons and even less attention given to other African American, Latinx, or Asian authors.

“It was a good education but not inclusive. It wasn’t until I got to college that I felt I could explore more,” she says. “I grew up in abject poverty. I went to Cranbrook Academy on a scholarship and when I spoke in AAVE people wondered why I was there. I had a 4.0-grade point average and people did make me feel like I was less than. When I went to college I tried to speak as much SAE as possible. I don’t mind it. I just try to make people comfortable.”

But, she says, people do make judgments.

Nordman is now working on a doctorate at Grand Valley State University and says she wants her students to understand that she does code switch and that just means she has amazing skills to be able to do that.

Johnson, who just received a doctorate from Fielding Graduate University after presenting a dissertation centered on Hip Hop Pedagogy, says studies have been done that amplify the beauty of AAVE and its vastness and complexity of lexicons and other studies that have demonstrated the need to include a focus on AAVE in the schools. A study done one year ago in Detroit found that there was a 3,000-word gap between Detroit school students and their suburban counterparts.

“We need to ask ourselves, is there a word gap or a language understanding gap that those in power aren’t acknowledging,” he says.

The topic for Johnson’s dissertation was the natural progression of sessions he had been leading at the Urban League for area students. The sessions are called Hip Hop for Change and he uses videos and other tools to teach students critical thinking, writing skills, and mathematics.

“They choose their own video and we walk students through this process of looking at the video descriptively to discerning it critically. They engage in an oral argument then move to a written argument. It helps them with their writing skills,” Johnson says. “I use AAVE when I talk to them. I don’t code switch.”

The math area of these sessions uses story problems that contain real-life situations that may be encountered in the African American community. As an example, Johnson says the story problem could include decision-making and the impact on a person who is caught with a certain amount of cocaine.

“This would talk about how much time they will spend away from their family and how much money they lost by not being employed,” he says. “Students begin to relate to text having fathers caught up in this system. I have started to share my lived experiences with my father being caught up in the crack cocaine game. This is demonstrating a sense of healing.

“It’s a liberating experience for students to engage in this way. They’re experiencing a revival and engaging in text that’s most natural to them. Imagine how it reaffirms their identity and acknowledges their humanity.”

Anderson says she thinks, “White people, in general, need to understand that we swim in a system that has its root in white supremacy and that there’s room for a lot of variation and that makes our culture stronger and better and makes our community stronger.”

Conversations need to focus on how “our European American counterparts have been privileged over the last several centuries and how that has put us at a disadvantage and a cultural disadvantage even with academic systems,” Johnson says. “It has created curriculums, pedagogies, and teaching cultures that have fostered a feeling of inferiority. We want to create cultural competencies and pedagogies that benefit African American cultures.”

Nordman says she intersperses her belief in the importance of cultural competencies throughout the school year and doesn’t save them for dedicated awareness like Black History Month. She says she feels fortunate to be part of a school system that supports this work and says this is not the case at the broader level where some teachers in other areas of the country have been disciplined for teaching students how to be anti-racist.

“The climate is such that you can’t teach this in a lot of places,” Nordman says. “We are able to have culturally sustaining pedagogy in all of our units.

“One of the things we are trying to prepare our students for is to be able to be well-rounded citizens and not have a limited perspective on the world. I want them to be curious individuals and ask a lot of questions. I hope when they leave here, they don’t just look at English as really boring. I’m hoping to get more kids behind this.”