Harvard University lifts up economic work of Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi

Waséyabek Development Company, established in 2017 by the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi of Calhoun County, has become a poster child for the Harvard Project on American Indian Development. Waséyabek is on pace to become a $1 billion company by 2040, and in recognition of its success, President and CEO Deidra Mitchell has been invited to serve as a guest lecturer at the prestigious Harvard-Kennedy School on March 24.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

The silencing of slot machines and gaming tables at FireKeepers Casino as a result of state-mandated closures during the pandemic amplified a decision made in 2011 by the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi Indians to establish its own economic development company.

That entity – Waséyabek Development Company – had a staff of 3 and was losing money up until 2018 when it began to turn a profit. It currently has a portfolio of 29 businesses which generated revenues of $75.4 million in 2022 and passive investments totaling $19 million in three different companies.

These revenue streams are keeping Waséyabek on pace to become a $1 billion company by 2040, says Deidra Mitchell its President and CEO.

“We are diversifying beyond gaming,” Mitchell says of the NHBP. “The industry’s become more regulated and there’s more competition. When COVID happened and casinos got shut down, that was really an eye-opener for Tribes.”

Although it is a separate entity from the NHBP with its own board of directors, Waséyabek was established with a clear mandate from the Tribes’ leadership to ensure a diverse portfolio as a way to hedge their bets. Tribal politics and business decisions are kept separate, Mitchell says.

Jamie Stuck, NHBP Tribal Chairperson, and ex-officio WDC board member says almost every tribe in Michigan now has an economic development corporation as a way to diversify their portfolios and lessen their reliance on gaming as their sole revenue stream.

However, not every Tribe is experiencing the same levels of success as Waséyabek. Mitchell says the failure rate of Tribes who have implemented economic diversification is estimated to be 80 percent. She credits the NHBP’s use of a model developed by Harvard University specifically for Native American Nations for that success.

“There’s a kind of a bible for lack of a better word about how to do economic diversification or diversification within Indian Country and it’s called the Harvard Project,” she says. “The Tribal Council, the board membership, and staff have worked hard to follow the Harvard Project and it’s not easy in a family of 1,600 people, all Tribal members, to do that and do it successfully.”

This success did not go unnoticed by the leadership of the Harvard Project which has invited Mitchell to be a guest lecturer at the prestigious Harvard-Kennedy School on March 24.

Mitchell will deliver her comments to students enrolled in Harvard’s Native Americans in the 21st Century – Nation Building II course. The class is led by Eric Henson, who is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and has been a research fellow/affiliate with the Harvard Project since 1998.

Mitchell will focus her comments on the best practices employed by WDC, which have set the foundation for the company to grow from $0 revenue in 2017 to $75 million at the close of 2022.

“Waséyabek Development Company has embraced the practices outlined by the Harvard Project, implemented them within their organization, and created a culture of positivity and growth,” Henson says in a press release. “Harvard students are fortunate to be able to hear about the real-world practical application of the Project’s principles from Ms. Mitchell.”

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development is the recognized leader in practical research, teaching, leadership development, policy analysis, and pro bono advising for Native communities, says information on its website.

“Since 1987, the Project has worked to uncover and support the conditions under which sustained, self-determined, political, social, cultural, and economic strengthening can be achieved by Indigenous communities. Indigenous peoples are undergoing a remarkable renaissance. This resurgence is powered by the nation-building movement among the 574 American Indian nations of the United States and companion exercises of rights of self-determination around the world. Harvard Project research repeatedly finds that success in this transformation is founded upon Sovereignty Matters, Culture Matters, Institutions Matters, and Leadership Matters.”

Stuck says the invitation is a tremendous honor for Mitchell that “reflects the positive and productive impact she and the WDC team have had regarding our Tribe’s economic interests. When you consider that there are 574 federally-recognized Tribes in the United States and Harvard has chosen a representative from our Tribe’s economic team to present information to their students, well it really speaks to the value that Deidra and her team are bringing to the NHBP Tribal Members and Indian Country, at large.”

Mitchell says the NHBP has been diligent about following this project model which complements their commitment to creating an economic diversification strategy that will benefit the next seven generations of tribal members.

“Often, when we think about economic diversification, we think of private equity firms which flip companies every five to seven years,” she says. “We plan for seven generations. We want to buy, hold and grow companies for the next seven generations. You do things differently when you know you’re holding an asset over time. There may be an instance here and there where we sell, but the majority of the time we buy it, hold it, and grow it.”

Waséyabek focuses on the acquisition of companies that have a strong history and leadership that want to stay three to five years through the transition. Mitchell says, “In the early stages, we have chosen to focus on established companies. Types of businesses that we would avoid are those that are at high risk for negatively impacting the environment or don’t agree with our tribal cultural beliefs.”

Early on the organization was focused on acquiring companies within a 125-mile radius of the NHBP’s Pine Creek Reservation in Athens. While they do have companies in Grand Rapids, Muskegon, Nunica, and Otsego, they also have invested over the years in businesses in other areas of the United States.

The funds used to purchase these businesses come from FireKeepers Casino. Mitchell says the Tribal Council has allocated 15 percent of profits from the casino to be used for economic diversification efforts. She says this is an important investment in the Tribe’s future.

“If something happened to the casino, we want our companies not to be impacted by that,” she says.

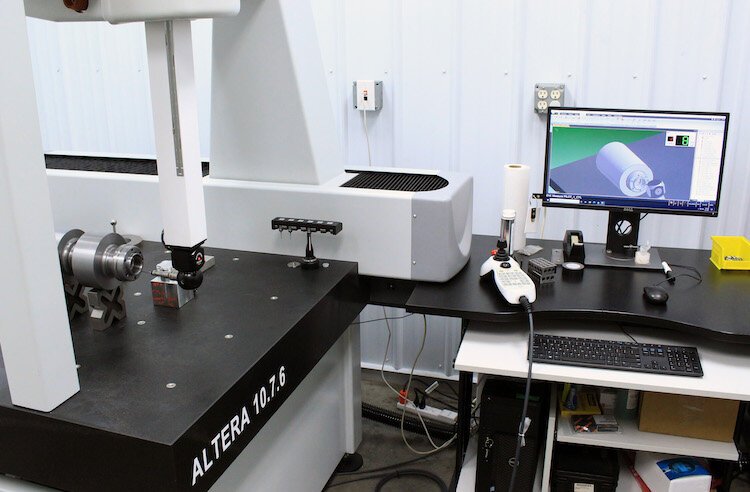

Waséyabek’s most recent five-year strategic plan is a reflection of diversification efforts to maintain and grow the current portfolio. That plan focuses on commercial real estate, the medical industry, and the defense industry and they already own companies doing work in these areas including Safari Circuits in Otsego and Baker Engineering in Nunica.

Not just growth for growth’s sake

When Mitchell was hired in 2016 to lead and help establish the new economic development entity, she had a staff of two. She now has 400 employees working in Waséyabek’s Grand Rapids headquarters and its other operations in Oregon and Washington, D.C. Eleven of these employees are Tribal members, a number she’s working to increase.

In addition to being an economic diversification arm of the Tribe, Waséyabek also is training younger Tribal members who are interested in working for any of the companies it owns.

“Dividends certainly mean money, but we also want to create those employment opportunities,” Mitchell says. “Dividends come in a lot of different forms. If we build a strong economic diversification engine, we’re returning dividends to support our Tribal members and government, but also businesses where Tribal members can get jobs.”

To fill the anticipated talent pipeline, Waséyabek works with the youth group at the Tribe and its Education Department to bring awareness to the kinds of jobs available at the companies it owns. There also is a Tribal Member Development Program which is a document that maps out a career path for Tribal members employed at the WDC family of companies and Leadership Exploration and Development program (LEAD) is designed to provide exposure to all of the companies within the Waséyabek portfolio to Tribal members, including those that are affiliated with other tribes.

“We want them to know what companies we have so that they can tailor their education or career aspirations to be employed by one of those companies,” Mitchell says. “This is an intensive six-month program Tribal members participate in to position themselves for success in any of the Waséyabek businesses they choose to work for.”

As an example, Mitchell cites Jessi Goldner, one of Waséyabek’s three original employees who started there as a receptionist. She has since gone on to earn a Master’s degree in Business and is now Waséyabek’s Director of Strategic Engagement and Compliance.

“We can tailor an experience and timeline that gives Tribal members the experience they need to step into the job they want,” Mitchell says. “It’s really important to sit down with them and identify what their interests are.”

Because Tribes for hundreds of years were denied access to equal economic and educational opportunities, Mitchell says, “We are just now graduating our first generations of college graduates. Waséyabek has done a good job of hiring Tribal members as experts if they’re available, but if not we’re hiring non-tribal members with the understanding that they are being trained to replace us.”

This type of holistic approach to doing business is one that Mitchell hopes the corporate world will take note. She says it’s possible that they may choose to integrate parts of the Harvard Project Model into the way they do business.

“I think I’m seeing a little bit more that companies are focused on the environment, social and governance issues,” she says. “The questions they need to be asking themselves are ‘How are we taking care of things other than the bottom line?’ and ‘What are our stakeholder and investor priorities?’ Through economic diversification and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, there are steps in that direction, but the Tribe just has a very unique mission that filters into its employee base too. It’s not just a profit-driven machine.”