KIA’s Black Refractions exhibit tells a shared story of complex people living in a complex place

Black Refractions is the kind of exhibit that takes more than one visit to take it all in. Second Wave's Mark Wedel and Rehema Barber, the KIA's new chief curator, reflect on the pieces that evoke deep responses from them.

Art appreciation is in the eye of the beholder.

But the beholder’s eye is the filter. And all art-beholders have gone through life experiences — some similar, some vastly different.

Second Wave wanted to get a good look at “Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem” before it left the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts and its only Midwest stop on its national tour, Dec. 8.

This is the biggest show of important African American works Kalamazoo has seen. With the inclusion of exhibits, “Where We Stand” featuring local black artists, and “Resilience: African American Artists as agents of Change,” with pieces from the KIA’s permanent collection, it’s massive.

Should we do this with just my eyes? Just my perspective? I’ve covered arts and entertainment for a couple of decades, but my life-experiences are on a foundation of being a white farm kid from Galesburg, Mich.

We reached out to Rehema Barber, the KIA’s new chief curator, who graciously accepted my request to tour “Black Refractions” with me.

I noticed some unease as Barber suspected my plot to have her give her views of each piece. Barber has detailed knowledge of each, and to have her also include her emotional/intellectual/cultural response to them all would’ve taken us hours past closing time.

She says with a laugh, “I think you don’t want me to talk about 92 works of art!”

The KIA had a list of 96 works to chose from the tour, they arranged the works in sections designed by KIA curators, and wrote their own section texts. “In a way, we curated this show from a curated section of works,” she says.

“To be clear, this is the first American institution that’s deinstalled its permanent collection, to show someone else’s collection in concert with their own collection,” she says. “It’s a huge deal. Not only for Kalamazoo, but for our region, our state, I think for our nation. We’re in a really interesting time, and art is something that builds bridges.”

She hopes that the exhibits will show all “that there is a commonality to our art experiences. We’re really disparate in our ethnicities or some of our cultural makeup, but then we’re also really similar.”

I’d gone through the exhibits a few weeks earlier. It was all stunning, but there were those works that grabbed me, made me stand and stare.

Barber knows each piece intimately. Of course, it would be hard for her to choose, but which —

“Oh my gosh, you’re about to ask me what my favorite is? Noooo!”

But she does have her favorites. So, we pinballed through the exhibit, taking in the pieces that grabbed us. Below is a sampling. This is hardly a “Top 10,” it’s more like an account of perspectives, beholders subjectively drawn to what speaks to them.

Your reactions may differ.

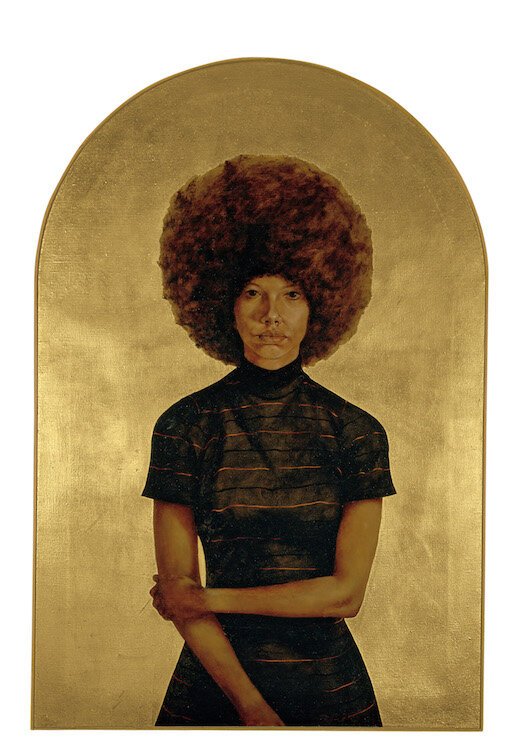

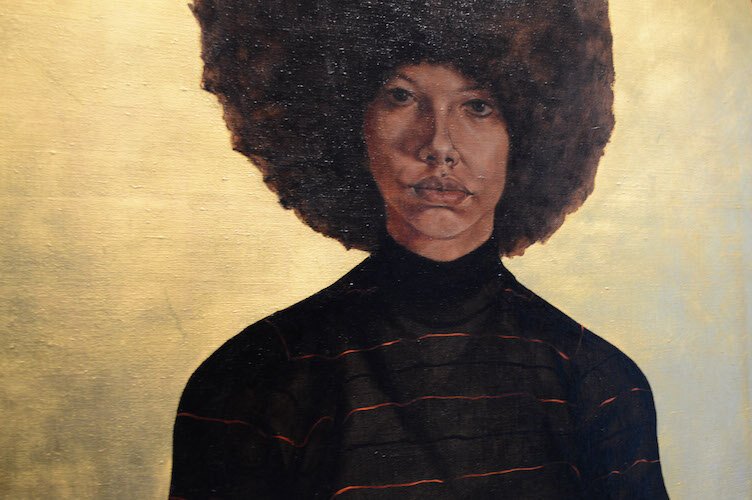

1: “Lawdy Mama,” 1969, Barkley Hendricks.

The first piece in the exhibit, what people see when they walk through the doors. In 2019, younger people might look at it and think, this is simply a realistic portrait of a young black woman in retro afro and clothes, highlighted by a background of gold leaf. But at the time, painting a black woman as a literal icon, in Renaissance style, was a political act.

“It’s funny because a lot of people politicize the work directly when really he was really into Renaissance painting, and has taken a regular, everyday person — this is his cousin — and elevated her to icon status. Her hair is the nimbus, what we would call the halo in art history, that deifies her, that elevates her beyond just a person. This isn’t just about making a political statement about the afro, it’s about showing the beauty of a regular person, a regular woman,” Barber says.

2: “Repugnant Rapunzel,” 1995, Chakaia Booker.

Asked what her favorites are, Barber says “I’m having a really big moment right now…” and heads for the abstract works section.

They are “favorites in my book, and the reason why I like them is the ability of abstract art to communicate narratives that you wouldn’t necessarily expect.”

People often ask “what can I get from this?” Some abstracts seem to be just exercises in color, line, and shape. She goes to Sam Gilliam’s “April 4, (Part III),” 1968. It’s a tall rectangle of somber blues covering warmer colors. Barber points out that this is a memorial painting, a response to the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination.

“But my favorite piece is this one…” She goes to what appears to be a tangled mass of bike tires on a pedestal in the middle of the room, Booker’s “Repugnant Rapunzel.”

The sculpture is in the shape of African hair in dreadlocks. “I like the fact that she uses this material, it’s such an ordinary material, rubber, rubber tires,” she says. In the European fairy tale, Rapunzel was a “lovely princess, locked in the tower.” She’s rescued by a prince who climbs up her braided locks of straight hair.

“When I look at this I think about the politics of African American hair, and how that has been such a huge space of a contested topic,” Barber says. “But I also think about the Belgian King Leopold who slaughtered the Congolese for rubber. There’s a lot of double entendre here…. We think rubber, it’s an ordinary product, but there are so many different layers and levels here that I really like.”

3: “Number 74,” 1999, Leonardo Drew.

“What other works were you really interested in?” Barber asks.

I liked “Repugnant,” but in the room of abstracts, well, “I’m a journalist, I’m a very literal person — things that are very abstract, exercises in color and shape, that’s cool, but…”

“You like something that’s got a little bit of a narrative, right?”

Yes, something I can dig into, and hunt for a story.

Among the abstracts, what really drew me in were the two huge panels of “Number 74.” Tiny wood boxes, some with wires or string or smaller wood blocks, but all overflowing with rust. Top quarter dominated by weathered items, most-haunting being children’s stuffed animals.

It seems like junk, rotting, rusting. The sheer size, around eight feet square, is overwhelming. The entire piece weighs 1,500 lbs, Barber says. They had to have six people on each panel working to get it on the wall, while scanning the floor for any detritus that might have fallen from it, looking for “what has been lost. But that is inherent in the piece, knowing what has been lost,” she says.

It reminds me of when I visited New Orleans a year after Katrina, I tell her. The city was still a disaster area, and outside all the abandoned houses, furniture and appliances and other evidence of people now gone had been left out to rot and weather for a year.

“I also see this as a memorial in some ways, because when I see all those ties and knots and stuffed animals, I think about the memorials you see on the side of the road,” she says.

Recognizable items are “things that at one point had happy uses, or got people where they needed to go — that looks like a shoe to me — or that, if it’s a book, maybe it really helped get someone through a hard time, or took someone to an imaginary world.” She points out teddy bears, a stuffed bunny, ” a source of comfort… it’s a wonder, almost.”

4: “Free, White and 21,” 1980, Howardena Pindell.

Another work I stood in front of, for its 12-minutes runtime, is the installation of “Free, White and 21,” Pindell’s conceptual art video. In it, she tells personal accounts of bias and racism, from being tied down by a teacher after requesting to use the restroom to being treated rudely as the only black woman in a white wedding party.

At times, Pindell covers her face in white gauze or peels skin-like dried glue from her face. She also appears in makeup and a blond wig as a white woman who discounts her stories, saying things like “you really must be paranoid,” and “you won’t exist until we validate you.”

“This is foundational, this particular work,” Barber says. It highlights “the expectations of black womanhood at that time — and sometimes this is still a prevalent idea, depends on who you’re talking to…. This used to be a prevalent attitude. This is how people addressed her — she didn’t make this up, these are things that people said to her at some point.”

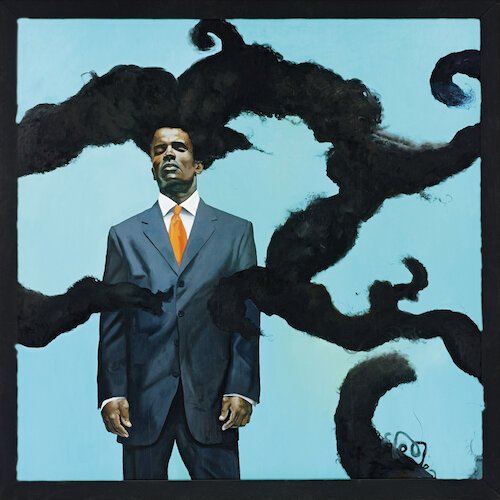

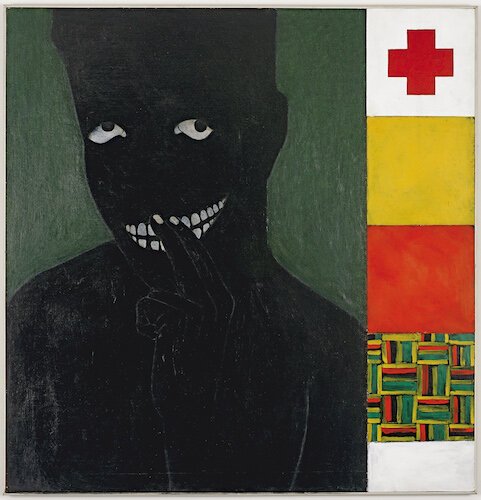

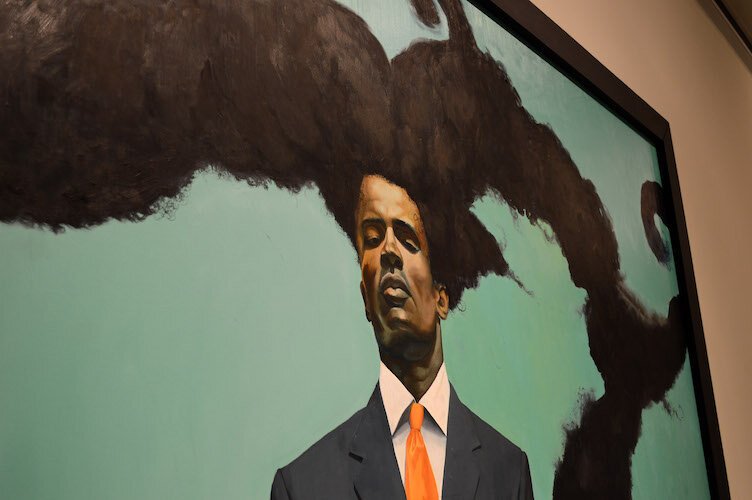

5, 6: “how i got over,” 2011, Henry Taylor; “Conspicuous Fraud Series #1 (Eminence),” 2001, Kehinde Wiley

Most of these works seem to be about a struggle with self-image, in this country, I mention.

Barber points out that we’ve drifted into the section called “Notions of Progress and Beyond.” “You start with stereotypes in imagery,” she says and points toward the section’s beginnings, including ”Green Chalkboard (Toothy Grin),” 1993, by Gary Simmons, a cartoonish stereotypical chalk drawing on a blackboard, and “Silence is Golden,” 1986, by Kerry James Marshall, painting with a pitch-black face showing only smiling teeth and eyes rolling up in a deranged manner, “then you move on to things that are more aspirational.”

The KIA curators have placed Taylor’s “how i got over” and Wiley’s “Conspicuous Fraud Series #1 (Eminence)” by each other, “because those are about aspirations that people have, that they can relate to.”

Taylor’s painting is of a woman jumping a hurdle. She’s Alice Coachman, the first African American woman to win a gold medal in the Olympics, in 1948. “In 1948, you win a gold medal, she didn’t return home a hero. She was still asked to go in the back door, to have a separate water fountain,” Barber says. “You train all your life to get to this level, to be at this point, and then you arrive home, it’s like….” Barber trails off.

Wiley, the most-well known of the exhibit’s artists, having painted President Barack Obama’s official portrait, paints an image of a black American still struggling to fit in while retaining his identity. “Conspicuous Fraud” features a realistic portrait of a man in a sharp suit, but his hair is surreally wild.

“You see all this controlled element, as far as the suit and the tie, and this is a representation of the ideal of professionalism in black masculinity, but then his hair is all askance, outward. It looks to me like dreams, when I think about it. How the hair is uncontrolled, really it’s more about an allusion to this ideal of one’s self versus this idealization of what black manhood should be,” Barber says.

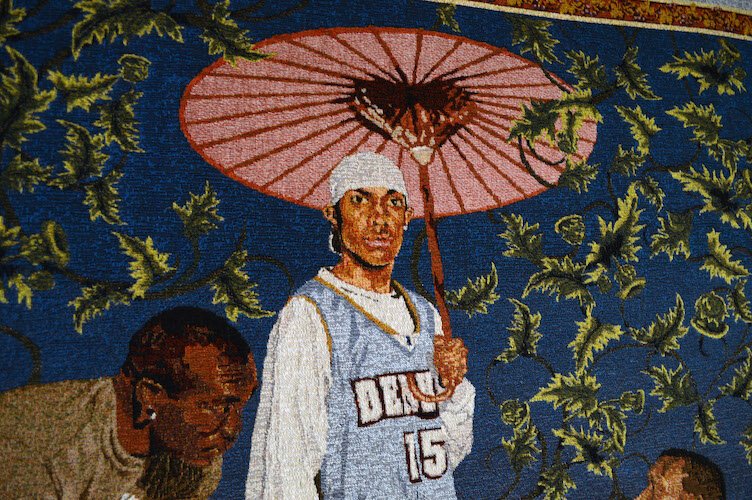

7: “Gypsy Fortune Teller” 2007, Kehinde Wiley.

Dominating a wall in the lower level is another piece demanding attention. A large fabric tapestry of a European Renaissance style, a lavish and rich presentation of five contemporary young black men hanging out.

Influenced by Hendricks’ portrayal of every-day African Americans in European art styles of around a half-millennia ago, Wiley has taken a form that would feature royalty or wealthy merchants and replaced them “with these gentlemen who we do not know, but who he certainly has a relationship with. The mood is very celebratory, the clothing is different,” Barber says.

During their day, tapestries like this would be about displaying wealth, showing family history, proclaiming status, she says. “Here, he elevates them but shows they have a different type of wealth and status, and that is just as valid as whatever the historical narrative has perpetuated in history.”

Wiley’s unspoken comment is “there was a time when we don’t see people of color, we don’t see Africans or African Americans or enslaved Africans at all in painting, but they were certainly present in these scenes whether they were servants, or whatever. You have to also know this work talks about representation — who’s being represented in history, and whose history is it, when history should be for everybody? It should be everybody’s history. So, yeah, I like this piece a lot.”

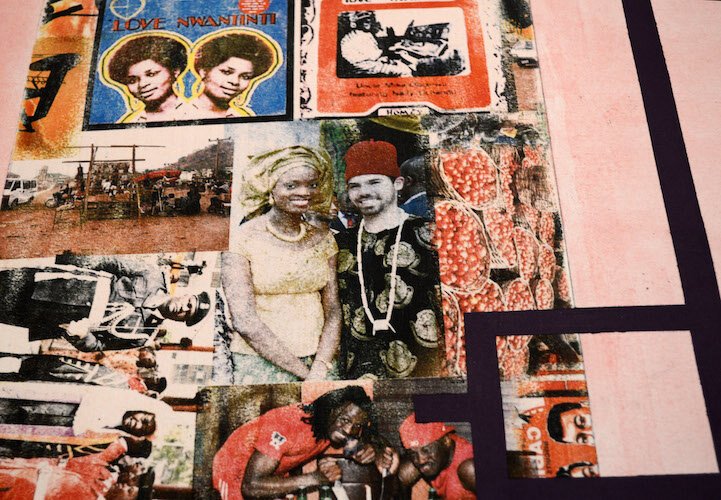

8: “Nwantinti,” 2012, Njideka Akunyili Crosby.

We seem to be wrapping up. I ask my standard last question: For those who haven’t seen this, what can they expect?

“Expect to be blown away,” Barber says. “I would also tell them to take their time. Come and spend a day here when you can kind of linger. Take some time to think about what it is you’re seeing, unpack it a little bit more than just looking at it sort of perfunctory, saying ‘oh that’s a nice painting,’ but also look at how the artists are trying to communicate with you. I also would say this is your only opportunity to see it in the Midwest, so if they don’t see it here, it won’t be back.”

But, still wanting to linger a bit more, I zero in on another work that had sucked me in — “Nwantinti.”

At a distance, it’s a large painting showing the love between the artist and her husband. But up close one sees it’s on Xerox transfers of photos of food, record album covers, kings, soldiers, weddings and of the two subjects: a black Nigerian woman and a white man.

“The artist has spent much of her life between Nigeria and here. Here she shows herself and her husband, who is white, in this tender moment. What I love about this work is she shows that love triumphs all, but she’s also talking about the tension of culture,” Barber says.

Titled after a popular ’70s love song in the region, the work is literally soaked with images of love, tradition, and culture. “It’s kind of amazing in that it shows the vast different experiences of Nigerian culture, but also the intersection of American culture, but also the intersection of how they can coexist, how they do coexist, how they are not so different after all,” she says. “I love this because it is so celebratory, so beautiful.”

It’s one of many examples of why people have to visit this exhibition, and not just rely on photos of the work. One has to see the actual object, to zero in on the rich details. “You have to be here. You have to see this,” she says.

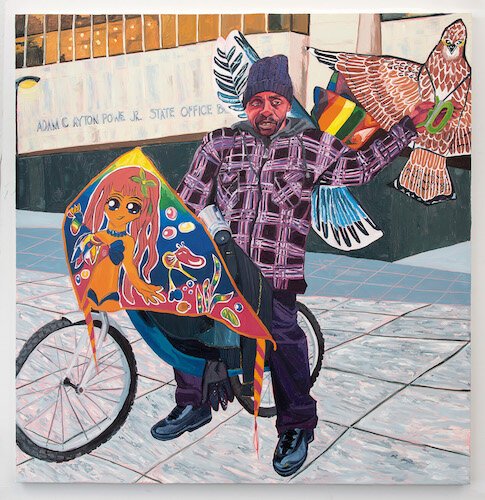

9: “Kevin the Kiteman,” 2016, Jordan Casteel

“And this one! Over here! If I had the money and a mansion to display it in, this’d be on my wall,” I babble.

A bright, colorful image of a man on a bicycle. He’s holding a couple of kites. The cartoon face of a wide-eyed girl on one contrasts with his weathered, aging face.

Casteel, artist-in-residence at The Studio Museum in Harlem would see him out in the busy courtyard, “clearly having the time of his life dancing and flying kites,” she’s quoted on the museum’s site.

“If you’ve ever been to Harlem on W. 125th St. it is intense! It’s busy, people are selling things on the street, there’s traffic, it is a hub,” Barber says.

“Here I feel like she gives us a sense of this person’s humanity — probably someone thought ‘this guy is a nut! In the middle of 125th Street flying his kite!’ But he’s found freedom, in a time and a place people might not necessarily think he should have freedom…. Black men in America, black boys, before they’re men, black children, are being penalized more than their white counterparts.”

Barber says this makes her think about Trayvon Martin, a black teen killed by George Zimmerman in 2012. “There’s no ability to have a moment of adolescence as a young black child in some ways. (Martin) wasn’t an adult, he was still a child. But they assassinated his character, said that he was a troublemaker in school, said that he smoked pot…. He didn’t have a gun, he was carrying Skittles, and some man was following him,” she says.

“I liken this situation here with that because he (the Kiteman) has been able to reclaim a sense of youthfulness and vitality, and a sense of lightheartedness that, I don’t think African American men normally get to experience. So I celebrate that!”

10: “Jerome IV,” 2014, “Jerome XXIX,” 2014, Titus Kaphar

Next to, and contrasting with, the “Kiteman” are two small wood hangings. Realistic faces of black men are painted on gold leaf. The lower halves of their faces are covered — each piece has been dipped in tar.

“Titus Kaphar is a hometown hero,” Barber says. He was born in Kalamazoo, 1976, and now lives in New Haven, CT. He received his MFA from Yale, and was awarded the 2018 MacArthur Genius award.

When searching for his father’s prison records, Kaphar found 99 men with his father’s name. He painted each man, based on mug shots, in the fashion of Byzantine holy portraits of saints, and dipped all in tar.

People might think since half of each’s face is obscured, “is he showing bandits?” Barber says. No, these are men representing the mass-incarceration of black men, the tar making them voiceless, obscuring their identities. The work has a heavy “emotional weight,” she says. “When these gentlemen come out, they’re still second-class citizens. We’re the only country that does this in some ways.”

Literal tarring was also part of the lynching of the past — “That’s a historical reference, there. It is heavy.”

She directs me to “Black Wall Street,” 2008, by Noah Davis, a painting recalling the massacre of black citizens in Oklahoma City in 1921. “This happened!” she says.

“We have to, as a people, a nation, remember our history because if we don’t we really will run the risk of repeating bad moments in our history.”

Much of the art in “Black Refractions” takes an unflinching look at racism in the past and present. But overall, “This show is about compassion and humanity,” Barber says.

The exhibit is showing a story, but not a singular story. It’s a shared story of a very complex people trying to live in a complex place.

“We’re not just showing one layer of a story, but we’re showing several layers of a story. And also showing how those stories intertwine and intersect. America is a melting pot — that’s what I learned when I was growing up.” It’s the KIA mission, “showing that we have a shared story,” she says.

She points to “Kiteman” and “Nwantinti” –“You can look at this and feel exhilaration, you can look at that and feel love.”

“It is a story,” Barber says, “that intersects and overlaps and is changing and growing and is so very much a part of anyone’s experience.”