Kalamazoo’s public health approach to gun violence opens doors to creative solutions, says expert

A single gunshot that results in a homicide costs $1.2 million, robs feelings of safety, and rips a gaping hole into a family and community. Ahead of the national curve, both Kalamazoo County and City have declared gun violence a public health issue which moves the emphasis from penalty to prevention. Gun violence prevention expert, Reggie Moore, spoke to a large audience of invested community members last week at the Kalamazoo Community Foundation, calling on Kalamazoo to become a "healing-informed" city.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Kalamazoo series.

Reggie Moore spoke to a Kalamazoo Community Foundation audience Thursday about how Kalamazoo could have its own “Blueprint for Peace,” a community-driven gun violence prevention plan that he helped develop for Milwaukee.

But the plan’s success all depends on the actions of the community.

“If you came believing I’m an expert, you’re in the wrong room. I am not here to save Kalamazoo, I am not here to tell you what to do. The solutions to community safety in Kalamazoo is in this room and it’s in your community,” Moore says.

Community-driven

This may not be the most violent time in America, Moore pointed out — that would’ve been the early 1990s during the crack epidemic — but during the COVID-19 epidemic, gun violence has increased.

“This is not the most violent time in this country, but definitely in terms of the numbers of homicides that we’re seeing, it’s extremely concerning.”

Gun violence at any rate demands the formulation of new strategies, he argues. “When we think about, again, the human toll that this takes, and the value of whose lives matter, it is important to understand how we got here — a culture of fear, inaction, obstruction, and indifference to doing anything about gun violence for far too long in this country,” he says.

“However, that has not stopped many of you in this room, and many other communities across the country, from doing something.”

Gun Violence, a public health crisis

Moore is the Director of Violence Prevention Policy and Engagement at the Medical College of Wisconsin and has been the Director of Injury and Violence Prevention for the Milwaukee Health Department’s Office of Violence Prevention since 2016.

When appointed by the city to be director of the office, his “non-negotiable” in accepting the role “is that the community needs to define the priorities, not just for the office, but for violence prevention in Milwaukee,” Moore says. And just as important is “that the city has to be responsive to what the community says.”

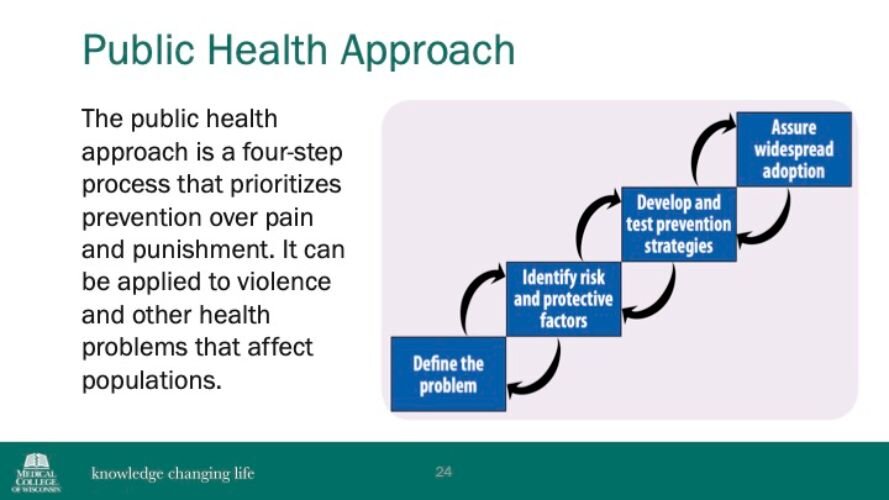

Kalamazoo County and City made the official declaration that gun violence is a public health crisis in 2021. Milwaukee is also taking a public health approach, Moore says.

Just as pollution might impact the physical health of an individual, what in a community increases the risk of gun violence?

Moore asks the audience, and replies include trauma, poverty, lack of education, lack of employment, and lack of mental health care.

“Violence can also affect a community. It’s not just an individual phenomenon, it’s a community phenomenon,” he says. In thinking of it in terms of public health, it’s vital to understand and address that some communities “have been divested in, have been violently abused through policy,” he says.

With input from Milwaukee communities hardest hit by gun violence, Moore developed the Blueprint. It was completed in 2017.

Shootings went down in the city, but then 2020 happened, and numbers jumped back up.

“In Milwaukee, we achieved a steady four-year decline in homicides and non-fatal shootings before the pandemic, and we have to get back there,” he says. “Before the pandemic, we averaged around 300 non-fatal shootings a year. Since the pandemic, last year, for example, we have over 800.”

“I saw here, in Kalamazoo, that you had fewer homicides last year than you had in 2021. That’s progress, but that doesn’t mean you take your foot off the gas. That actually means it’s time to double down. because if you don’t, then things will start to creep back in the wrong direction.”

“Pain-based groups”

Moore went into the fine-grain details of the Blueprint and related studies, down to how Tuesday nights were next to Fridays in the high number of shooting victims showing up at Milwaukee trauma centers.

“Friday wasn’t surprising. Tuesday, we haven’t figured it out. One theory is Taco Tuesday — a lot of bars have specials, and we know guns and intoxication don’t go well together.”

Such data is important, “because it forces those types of conversations and consideration, and it can even inform when your outreach workers are out on the street, and which areas they’re working in.”

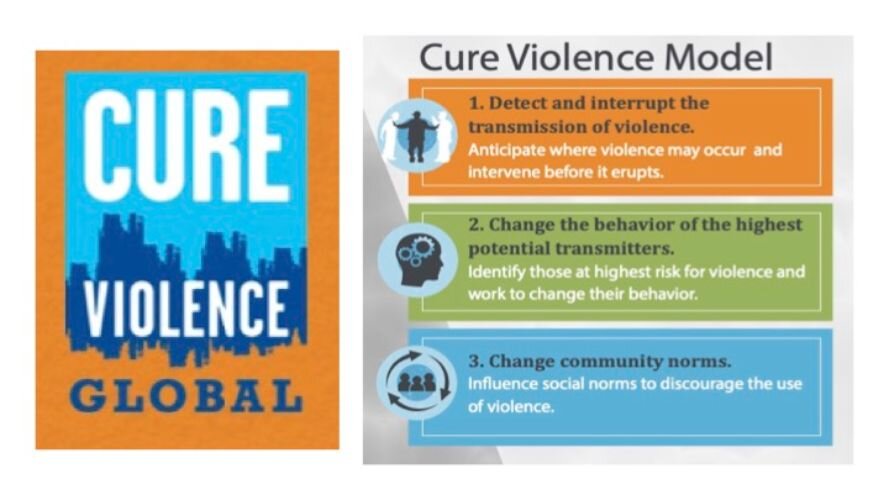

Milwaukee’s outreach workers go to where violence intervention and mediation is needed — neighborhoods and hospital trauma centers.

They work to break up cycles of retaliation and counter-retaliation. But that work has been difficult in recent years.

Youth haven’t been forming what one might think of as traditional gangs, he pointed out. “We have a lot of what we call pain-based groups…. It’s young people creating groups named after young men who’ve been killed. And they’re warring with other groups, usually off of social media, who are disrespecting or were involved in the homicide of that young man. And it’s typically young men.” There are two such known groups in Milwaukee that have “contributed to over a hundred shootings in a year, and they all skew under 18.”

There used to be a hierarchy of leadership in gangs, older leaders who would be involved in mediation to “call off a beef. That doesn’t exist now. And it’s hard to negotiate with a leader who is 14 years old.” They have the impulsivity that one would find in any younger teen, plus “the pain and trauma and rage that they feel in terms of retaliation.”

On the streets, intervention may be difficult. It may be more effective in their “hospital-based violence intervention program.”

Anti-violence workers come to the hospitals

Milwaukee’s anti-violence workers show up at hospitals to talk to victims and their friends and family. “If you are having a hard time convincing somebody to change their life on the street, they are more apt to listen to you in that trauma bay,” he says. “They are more receptive to the message, and to reevaluating their life.”

A methodical process begins as the victim comes in, and is identified as someone who’s been at a high risk of being a shooter or victim. Outreach workers talk to friends and family in the waiting room — “sometimes retaliation will start in that waiting room,” he says.

Moore gave an example of a victim who was shot 12 times in front of his home and family. “The patient shared a fear of continuing violence from the people who shot him.” He was to be discharged quickly, but the trauma team was told he’d be going back to an unsafe housing situation. “We were able to delay discharge, work with the county to find alternative housing for this individual,” and the victim was able to be housed in a safer area, Moore says.

This kind of work needs partnership and collaboration among many individuals, city offices, and public services. It also needs everyone working for the city, from police officers and first responders to people working at city desks, to know “trauma-informed care.”

“We actually worked with the city council to mandate that all city employees who have more than 60% of their working day in contact with the public, had to be trained in trauma-informed care,” he says.

Someone might be paying their water bill, “and they’re upset and irate. It might not have anything to do with the person behind the counter. We take it personally, right, in customer service?” Like cops on the street, such city workers need to know “how do you de-escalate that situation?”

Moore hopes for a “trauma-informed city — which I like to refer to as a ‘healing-informed city,’ instead of ‘trauma.'”

The moral argument, the financial argument

Moore brings up an opinion piece by Wisconsin ER doctor Megan Schultz, “What keeps an ER doctor up at night: ‘The sound a mother makes after her child dies.‘”

Schultz writes of how “I grew accustomed to seeing bullet-riddled children.” And of how she constantly faced grief, fear, and lasting trauma around shootings.

She writes, “Moms are not always present when their children die of gunshot wounds. Sometimes the mom doesn’t even know yet that her child has been shot. This time (as Schultz tried to save a patient), the mom was in the corner of the Trauma Bay. She screamed and screamed as I announced that her son was dead. The screams of a mother after her child dies are not of this world. They are guttural, they are ghostly, and they will haunt you for the rest of your days. It is the ripping of the strongest tether, the cruelest injustice a human being could endure, the spectral response to George Floyd’s cries.”

“Doctors and nurses see this on a regular basis,” Moore says. They have to be “combat trained and experienced… Imagine having to have those levels of skills to save human lives on the streets of our cities.”

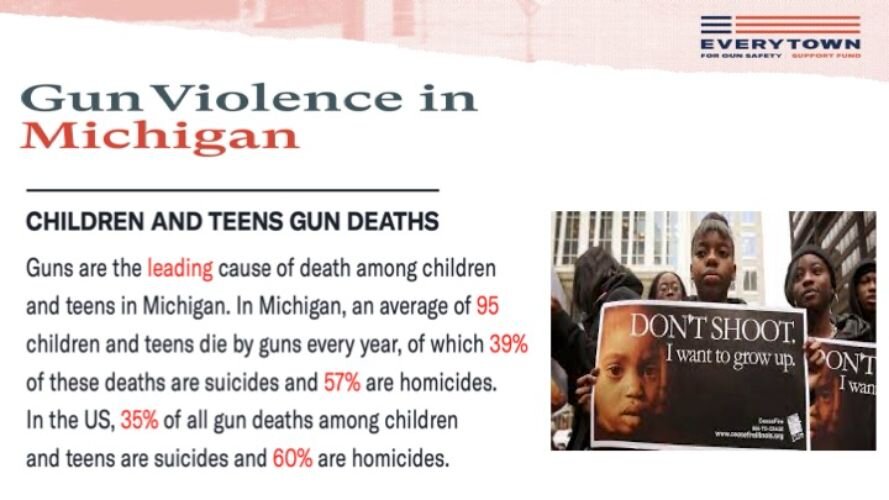

Moore then points out the financial costs of each shooting. Per homicide, including hospital costs, crime investigations, the criminal justice system, incarceration, etc., “a single gunshot costs $1.2 million per homicide.” For non-fatal shootings, it’s “close to $700,000 per injury, per shooting,” he says.

“We can’t win the moral argument? That no kid in our country should have to be afraid in our country of being shot? Or feel that they have to carry a gun to feel safe? Then maybe making a financial argument could work. But as we know, that sometimes does not work, either.”

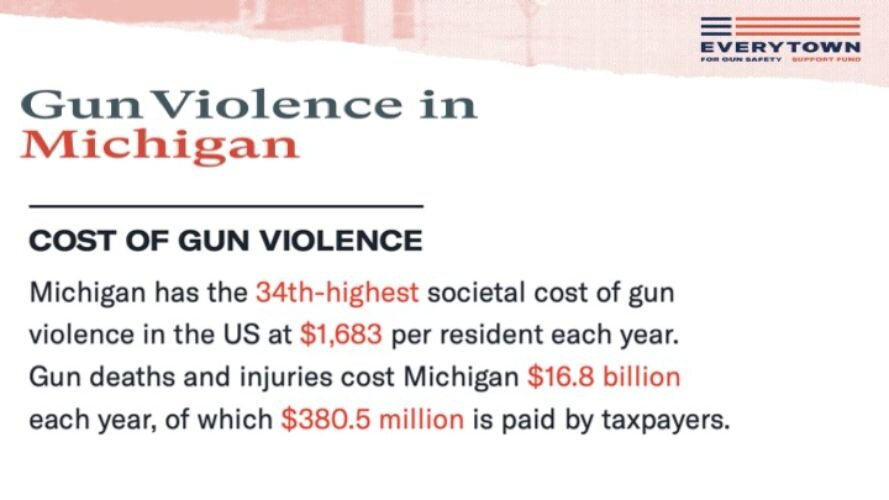

There is the “human toll, the psychological toll, and then also the financial toll” on society. “Michigan has the 34th highest societal cost from gun violence, $1,683 per resident each year. Gun deaths and injuries cost Michigan $16.8 billion each year, of which $380.5 million is paid by taxpayers,” Moore says.

Taking a public-health view of violence, Moore makes it obvious that disease prevention is ultimately less costly than the disease. “If an after-school program is in the same community that has a high risk of violence, the value proposition should be clear. The return on investment for prevention should not even be an argument, because I’m pretty sure it costs less than $1.4 million per kid in that program.”

“We have a criminal justice system. We can guarantee a cage, and guarantee prosecution… but we should be able to guarantee an after-school program. We should be able to guarantee access to quality education,” he says.

Moore says that “every system, every role, every organization and institution in the community, whether it’s early childhood, primary healthcare, community organizations, social service providers, the media, everybody has a role to play in understanding and addressing violence as a public health issue.”

“We can’t piecemeal our way out of this, we can’t say, okay, we’re going to give $10 for violence prevention and continue to give $100 million for cops, courts, and cages. At the end of the day, there has to be an equitable investment if we are truly serious about addressing this comprehensively. No one entity can do it alone, whether we’re talking about law enforcement, whether we’re talking about an intervention program, we all have to have a stake in addressing this.”

Reversing the upward trends in gun violence might seem like a hopeless task. Near the end of his talk, Moore shows a quote from California Pastor Michael McBride, who’s been active in the gun violence prevention movement: “Hopelessness is more deadly than a bullet.”

Moore says, “If we don’t believe that we can change this, it won’t happen.”

Kalamazoo connection

While introducing Moore to the audience, Jennifer Heymoss, Vice President of Initiatives and Public Policy for the KZCF, told the audience something her young child said.

As her husband dropped their son off at school, he said “Daddy, did you know a six-year-old shot his teacher at school?”

In an interview after the presentation, Heymoss says,”It came out of nowhere, we don’t talk about that in front of him.”

Then their child added, “Well, maybe he didn’t see the sign that says ‘no guns on the playground.'”

“That’s what got me more than his first comment,” Heymoss says. Her son was very aware of guns, the fear of guns getting into schools, and of living in a society where a shooting could happen anywhere.

It’s a reason why she’s overseen the KZCF’s work in reducing gun violence, “so that when my son is my age we will have shifted the needle a little to change the culture and positively impacted the community.”

Heymoss met Moore through other Midwest community foundations, forming a learning network to see how to approach gun violence in a public health framework. This was at the same time, in 2021 when Kalamazoo County and City declared gun violence a public health crisis.

His work inspired the KZCF to put together a Kalamazoo “Blueprint for Peace” in 2022.

Moore was a “powerful advisor” on the subject, so he was invited not only to speak at the KZCF but to participate in training, sharing what Milwaukee has learned, she says. “This was the original work that he did in Milwaukee, and I just want to honor that foundational knowledge.”

Much of Moore’s tactics have been put to use by Kalamazoo groups working in gun violence intervention and in changing the conditions in neighborhoods that can lead to violence. Representatives from Urban Alliance, Gun Violence Intervention, and Interfaith Strategy for Advocacy and Action in the Community were present, among others. Also on hand were representatives from the City and County governments, and Kalamazoo Public Safety.

After Moore’s talk there was a break for lunch that had more networking and talking about collaborating than eating, it seemed. “What I heard in the lunch was an excitement,” Heymoss says, an excitement about looking at gun violence as a public health issue. “I heard people making connections who’ve never spoken (with each other), who’ve done the work.”

During lunch, Kalamazoo Vice Mayor Don Cooney summed up what he got out of Moore’s talk: “I think public health is the way to approach this whole thing. We have to emphasize prevention, we can’t just be working on trying to get people incarcerated. That’s the whole wrong approach,” he says.

“I just think about what are our priorities, and what are we going to invest in. Investing in our people that are at risk pays off for the whole community,” Cooney says. “There are a lot of good things happening in the city, but I don’t think we’re together… I think the next step is a collective response, and to put in the resources people need to make this happen.”