As if they didn’t have enough worry this season, Michigan residents have a new misery headed their way, the beautiful, voracious, spotted lanternfly.

It’s not here yet. But it has the potential to wipe out entire vineyards, shut down U-pick orchard outings, and ruin outdoor recreation at a time when people are flocking to parks and campgrounds.

It can devastate crops, spread mold over patios and vehicles, and kill backyard trees.

Unlike some other invasive insects, such as the emerald ash borer that targets a single species, the ash tree, the spotted lanternfly has at least 70 hosts, and spells trouble for everyone from growers and vintners to vacationers and homeowners.

In Pennsylvania, where it’s been around for about 6 years, the tally of its annual damage stands at about $50 million—and growing.

Sharp eyes outdoors currently offers the best line of defense, and the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development this week asked the public to be on the lookout for the colorful one-inch fly or its immature distinctive black and white life stages, and to report any finds to authorities ASAP.

They also urge travelers from Pennsylvania and other states where the insect has been found — Delaware, Virginia, New Jersey, Maryland, and New York — to check their vehicles and equipment before entering the state of Michigan for possible egg masses.

The insects are easy to spot, too.

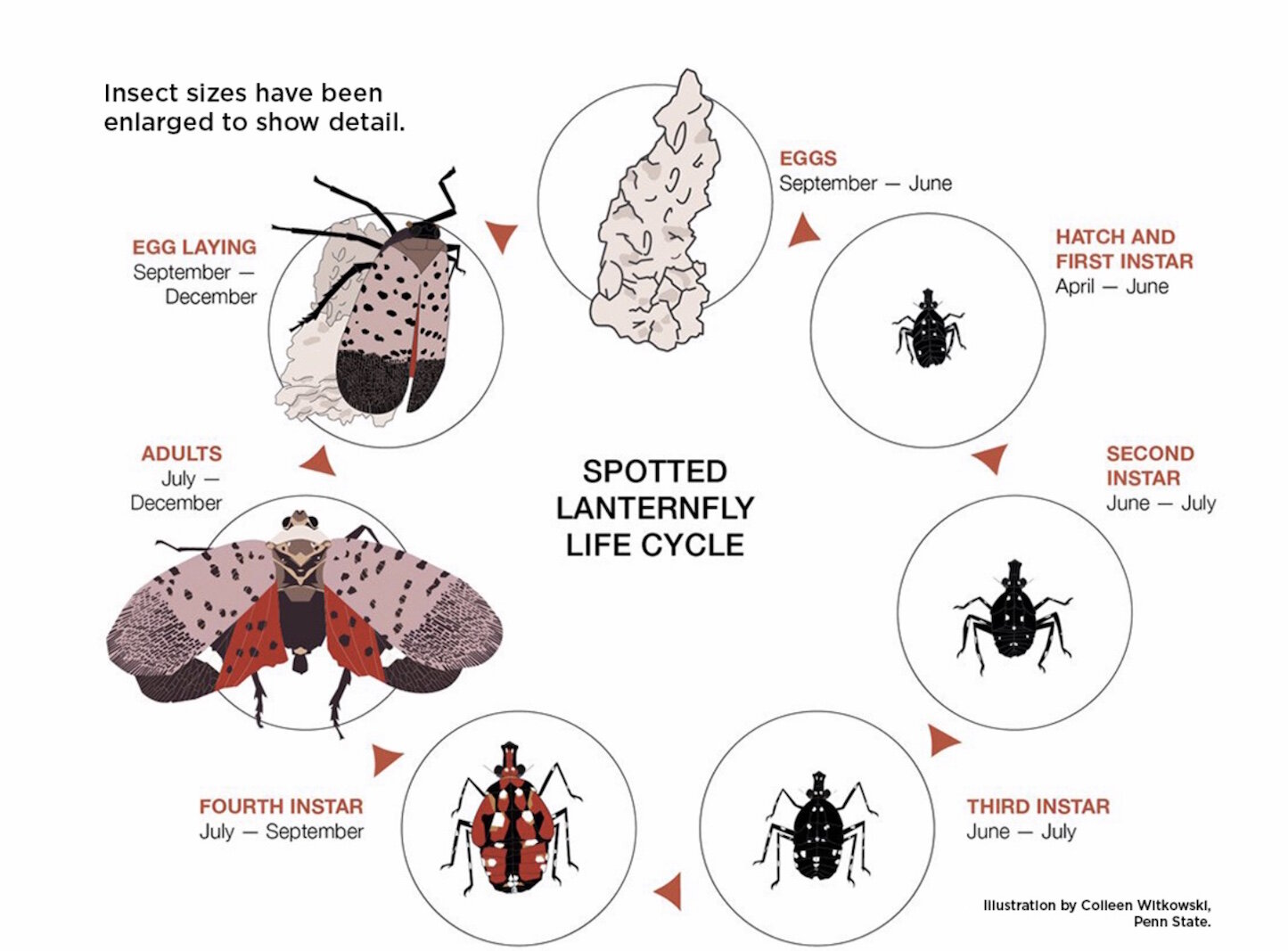

This time of year, in its nymph stages, the lanternfly appears as black beetle-like insects with white markings or reddish-orange with black and white markings.

The nymphs eventually develop into adults, about an inch long and half an inch wide, with grayish forewings with black spots and red, white, and black striped hindwings. A few adults may appear in mid-summer but they are most common in late summer and fall.

“Prevention and early detection are vital to limiting the spread of spotted lanternfly,” says Robert Miller, invasive species prevention and response specialist for MDARD. “Spotted lanternfly cannot fly long distances, but they lay eggs on nearly any surface, including cars, trailers, firewood, and outdoor furniture. Before leaving an area where a quarantine is present, check vehicles, firewood, and outdoor equipment for unwanted hitchhikers.”

About Spotted Lanternfly

An invader from Asia, the spotted lanternfly feeds on vine fruits and trees, piercing stems with its sharp mouthparts and sucking the sap, like a kid with a juice box.

It excretes the sugars from this diet as a waste substance known as honeydew.

The honeydew rains down in a sticky mess, attracting stinging insects such as wasps and yellow-jackets to create a secondary nuisance. And as if that were not bad enough, the honeydew sets up conditions for a sooty black mold that coats leaves and vines, blocking photosynthesis and weakening the plant.

Pennsylvania scientists report that grapevines attacked by hordes of these pests either fail to produce fruit or die outright in the following year.

The honeydew they leave behind can also foul cars, outdoor furniture and yards, and both the stinging insects it attracts and the molds that grow on it complicate harvests and ruin outdoor outings.

Miller says it’s difficult to predict how the insect might behave in Michigan. Both the climate, and the distribution of its favorite host tree, the tree of heaven, are different here than in Pennsylvania, Miller says.

But based on how the insect has attacked in that state, it appears Michigan’s grape industry may be most at risk, Miller says. “It also has the potential to damage stone fruits, apples, and other crops in Michigan’s fruit belt as well as important timber species statewide.”

Voice of experience

Heather Leach, Extension Associate at Penn State University’s Department of Entomology, grew up in Traverse City Michigan, and is well acquainted with Michigan’s wine industry and its fruit belt. Leach says Michigan residents can help protect their state best by stamping out the insect as soon as it’s found here before it can get a foothold. That buys science time to develop sustainable controls.

“In Pennsylvania, the damage we’re seeing in vineyards is pretty horrible,” Leach says. The heavy infestations can lead to complete vine death, so the risk of losing complete vineyards is high.

“It feels like a bug apocalypse,” Leach says.

But it’s not only farmers and growers who need to worry.

The nuisance factor of these insects is also high.

It doesn’t bite or sting, and it doesn’t invade homes the way stink bugs do.

But the large adult flies gather in high populations, “and that in itself is a problem,” Leach says. “It becomes so bad that just walking from the car across the parking lot to the grocery store they’ll dive bomb you, crawl up your body.

“It’s a total major gross factor,” Leach says.

“People here, the first one they see they think ‘oh, it’s so beautiful,’” she says with a wry laugh. “But the game really changes fast,” she says, and soon they are swatting and swearing.

One gleam of hope?

As the insect approaches Michigan (It’s not if, but when, Leach says) the only thing other states have against invasion is early awareness, and it really can help.

“The more eyes in the community to report the spotted lanternfly when they see it, it gives us a huge leg up in the whole operation to delay its spread until better control solutions are found,” Leach says.

Scientists at MSU and at Penn state are partnering with other universities to study all aspects of the insect’s life cycle to come up with controls.

“We’re trying to establish a network of trained professionals, a tag team to knock it out with many little hammers,” she says. “It’s unlikely we’ll find a silver bullet.”

“We are doing a lot of prep work,” Miller agrees, coordinating response teams through state and federal agencies and universities, developing communication materials and getting plans in place for potential infestations.

Setting a trap

The first step, preventing its entry or stopping its spread, is underway now with the alerts and public education efforts.

If populations are found here, the next step will be response, determining its distribution, and enacting control methods.

That means more than simply spraying the insects with chemical controls, Miller says, because their numbers can be so high that the next day, more move in from areas that were not sprayed.

One control tactic researchers are preparing for, if needed, is the creation of “trap trees.”

Spotted lanternfly strongly prefers a plant species called tree of heaven, Miller says, “so you’d kill all of the tree of heaven, in an area, leaving just a small percentage behind. Those trees you with treat insecticide.”

The lanternflies suck up the treated sap and die before they can damage other plants. That method is especially attractive because few other insects would be affected. The tree of heaven is an invasive species, and few other insects feed on it.

“Tree-of-heaven grows almost weed-like in Mid-Michigan,” says Paul Dykema, owner of The Visiting Arborists and past forestry manager for the city of Lansing.

“They take advantage of situations where all other vegetation has been removed. To have someone search townships to find nearly all of these trees would be a daunting task.”

That’s why MDARD also welcomes reports of tree of heaven locations, which are currently being added to an invasive species database.

“Right now we are working with USDA APHIS,” Miller says, to develop a map of tree of heaven locations in the state.

Report this species:

To report suspect adult or immature spotted lanternflies take pictures if possible, record the location, and try to collect the insects in a container. If you see suspect egg masses or other signs and symptoms, do not disturb them. Take photos if possible, note the location and report it to:

Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, MDA-Info@michigan.gov or phone the MDARD Customer Service Center, 800-292-3939.

• Or use the Midwest Invasive Species Information Network (MISIN) online reporting tool

• Or download the MISIN smartphone app and report from your phone.

Citizens can report tree of heaven here or they can call the customer service line.

Folks can also learn about invasives here.

For additional information on identifying or reporting spotted lanternfly, visit here.

Michigan’s Invasive Species Program is cooperatively implemented by the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, the Department of Natural Resources, and the Department of Agriculture & Rural Development.