Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Calhoun County series.

Michelle Simms says she always knew she was a Native American, but tribal culture and traditions were never passed down from her parents or grandparents. This history wasn’t taught as part of the educational standards for Social Studies at any of the schools she attended either.

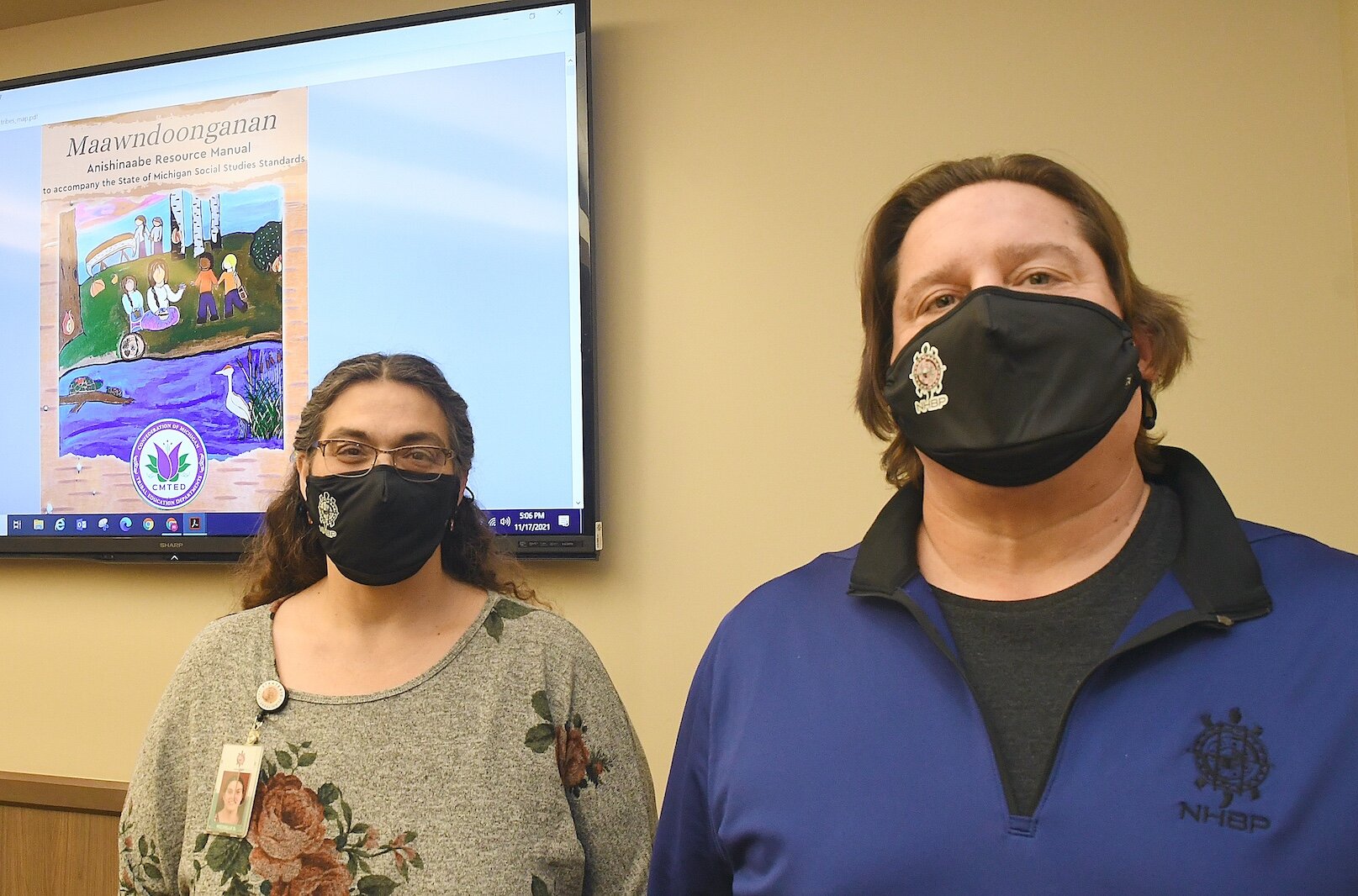

“I remember growing up and not really being connected to my own culture. I never really had any Native American teachers or friends,” says Simms, a Pre-K thru 12 Educational Specialist with the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi and a member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. “I just remember not ever really feeling like I fit anywhere. I don’t think I ever felt like I was really missing anything or wondering why Native Americans weren’t represented in what I was learning as a student because I never learned it myself from my family.”

But, this absence of curriculum focused on Native American culture and lack of an accurate accounting of their history is about to change with the use of an exhaustive, thorough, first-of-its-kind resource guide developed for educators in the state of Michigan by indigenous educators. Their efforts were guided by the all-Indigenous-women-led Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Departments (CMTED), which wanted to help Michigan educators better understand the rich history and contributions of Indigenous peoples in Michigan.

The 12 federally recognized tribes in Michigan are each represented in CMTED and they all had a voice in what they wanted to have included in the resource guide, says Melissa Isaac, CMTED spokesperson and the Tribal Education Director for the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan.

The Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Departments’ resource guide is intentionally focused on the more inclusive social studies standards adopted by the State Board of Education in June 2019 that reference tribal nations.

(To see the lesson, click here.)

“It is the commitment of CMTED to support the role that K-12 education plays in educating Michigan’s students and educators about the original people of this land,” says Isaac, CMTED Giigdookwe (leader or chair in Anishinaabemowin). “In turn, it is the ethical responsibility of Michigan’s K-12 educators to make the personal and professional commitment to learn about the land on which they live, work, and play. Intentional and collaborative relationships between CMTED and the K-12 teaching force will help ensure a more informed Michigan citizenry.”

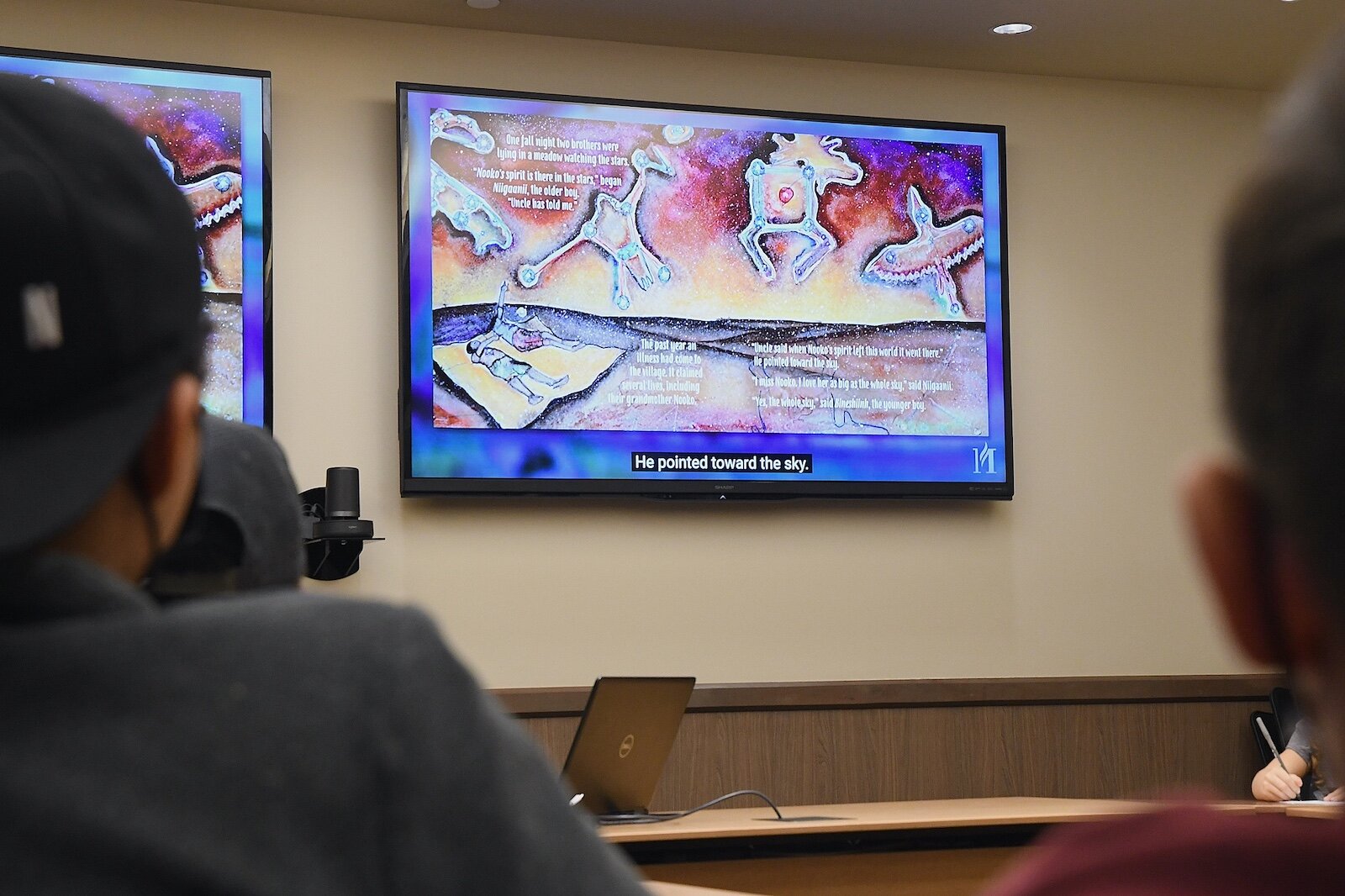

For the first time in Michigan history, Isaac says the CMTED has a platform to share Indigenous-developed and Indigenous-vetted educational resources with Michigan’s educators. The initial resource on the website — Maawndoonganan: Anishinaabe Resource Manual — contains CMTED-endorsed instructional materials such as books, podcasts, videos, and websites.

Michigan’s 12 tribes were among groups representing other demographics in the state that were given the opportunity to have their histories and cultures represented in the state’s public-school educational standards for Social Studies through an initiative championed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

“It’s important that you have the input of the 12 sovereign nations within the state to have a voice about how their history, culture, and values are portrayed and how they’re made available to educators in Michigan,” says Jamie Stuck, NHBP Tribal Council Chairperson. “This was a four- or five-year process for the CMTED and at that time you had multiple people working on it, including representation from the Michigan Civil Rights Department and they were able to work together in great partnerships to make it happen.”

Isaac says representatives with the Michigan Department of Education and Michigan State University worked with CMTED.

What students had been getting previously was a second-hand interpretation of Native American history absent of any meaningful input from Native Americans in Michigan, Stuck says.

“It was not decided by the tribes how they would be portrayed in history books and their history and culture doesn’t come through in the stories in those history books,” he says. “It’s important for young adults and elders, many of whom have not had the opportunity to immerse themselves in that history.”

While Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Departments members did not get everything they wanted to be taught included through the K-12 educational Social Studies standards process, Isaac says it’s a start. The Native American history and culture identified by CMTED are being incorporated into the state’s public schools’ standards.

“We fought hard to get the standards updated and inclusive of us,” Isaac says. “We are for the first time referred to by our original names as Anishinaabe people specific to the tribes here and our identity is by tribe. The teaching of our history doesn’t just stop after a certain year.”

Isaac and her CMTED colleagues made sure that different levels of tribal government were accurately identified and that Mother Earth is given a voice so that students will learn that tribes have always been good stewards of the land they occupy.

Simms, a Native American educator for six years who taught at all elementary school grade levels for 20 years prior to joining the NHBP, says when the Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Departments was seeking input and help with revisions to current standards, she jumped in to work with a group focused on Indians and Indigenous knowledge. Through that work, she began to get a better sense of why she never felt like she quite fit in as a student.

“I realized what I learned in school was about Indians of the past and I never really learned about who I was because there wasn’t anything taught beyond those brief mentions,” she says. “Certainly, if I went back into the classroom now, I would think about how important it is to have Native American teachers and how that would have shaped me.”

The resource guide, Simms says, is “authentic and put together by many, many people who know the culture. As a teacher, if I would have had this resource, I would have learned about myself and not been in the dark.”

In a press release acknowledging November as Native American Heritage Month, State Superintendent Michael Rice, says, “We all benefit from an understanding of our separate and collective histories, from a knowledge of the fullest breadth of history. The social studies resources developed by Michigan’s tribal educators bring us closer to that understanding.”

Not surprisingly, Isaac says tribes in Michigan get “a lot of requests” from media and the schools to do presentations in November because it is Native American Heritage Month.

“One thing I want to stress is that our history and tribal nations should be taught year-round, not just during an event or in November. Hopefully, this will happen with the resources we’ve created,” she says.

Different tribes, different education models

That level of understanding is expected to increase among all students, as Michigan’s educators use the resource guide designed to teach to each grade level, Isaac says.

Prior to the creation and adoption of these statewide resources, each of the 12 tribes in Michigan established their own educational systems along with resources designed specifically to teach their culture, language, and customs to anyone who is tribally affiliated. However, what is taught in those systems varies depending on the finances available, Isaac says.

“Here in Mount Pleasant on our reservation, our education department consists of an early childhood program for 2-, 3-, and 4-year-olds which teaches the Anishinaabe language and a K-5 tribal school to educate the children living here,” Isaac says.

The boarding schools set up by the federal government beginning in 1860 were designed to strip Native American children of their language, culture, and customs. As a result, Isaac says, indigenous languages were facing extinction and there was a dramatic decrease in the number of Native Americans who could speak these languages.

“Our youngest learners work with tribal members who speak the language as their first language or are fluent speakers,” she says. “Those ages are a prime time for language acquisition and it’s taught right here on the reservation.”

The two schools, located in the same building, have certified teachers who teach the same curriculums as those taught in the public schools. The difference is the environment offered at the tribal schools.

“When you drive up to our school, on the outside it looks like a tiny, little place, but as soon as you walk in, you smell sage and sweetgrass, which we burn a lot of,” Isaac says. “It smells like my grandma’s house.”

Paintings depicting florals and different tribes cover the school’s walls and there also are mini-teaching lodges where students can go when they need a comforting space.

Isaac says a “small percentage” of the tribe’s students attend the K-5 school and there are a total of 110 students in each of the tribe-operated schools, with the majority – about 700 – attending public school in the Beal, Mt. Pleasant, or Shepherd school districts.

The biggest challenge for these students when they transition from their tribal school to public school is going from a small, close-knit learning environment to a larger, more diverse learning environment.

“They need a lot of support,” Isaac says. “According to assessment scores, we’re the most underperforming group, with the lowest graduation rates and the highest dropout rates, so the federal government provides funding for schools that get so much per student where there are indigenous learners.”

This funding comes through the federal government’s Title 6 Civil Rights Act of 1964 which includes providing education to Native Americans. This federal funding is also distributed to school districts in Beal, Mt. Pleasant, and Shepherd which the tribe’s students attend.

“The whole goal of this funding is to help our students,” Isaac says. We collect that for the three school districts and the tribe provides supplemental funding.”

While Title 6 funding is available to every school district in Michigan that has Native American students as part of its student body, not every one of the 12 tribes has a school similar to what is offered by the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe.

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians is involved with a charter school and offers adult education classes in which tribal members receive a stipend to cover the cost of earning their GED (General Educational Development) test. In Manistee, the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians provides tutoring services and school supplies.

Simms says her work at the NHBP focuses on providing services such as tutoring for students, or going into a classroom to read books about Native American culture, or sharing items unique to that culture, such as indigenous foods. She says she also buys school clothing for students and helps them get registered for anything from driver’s education classes to renting a musical instrument.

“We don’t have an actual school. I serve as a conduit between the public schools our students attend and the tribe,” Simms says.

Over the past five years, she has worked with about 415 students. Currently, there are 25 preschoolers and the remainder are in grades K-12. Because NHBP tribal members are scattered throughout the United States, Simms works with some of these students living in other states and provides them with the same resources as local students.

“That’s how vastly different they can be,” says Isaac of the way that each tribe structures its educational efforts.

A resource guide for students of all ages

Although designed with students in mind, Stuck says he thinks the resource guide will be accessed by tribal members who didn’t learn about their history and culture at school or at home.

Stuck says he was always aware of his heritage as a member of the NHBP, but that the teaching of language and traditional ways by his parents and grandparents was limited.

His grandmother would come into his elementary school classroom and talk about his grandfather’s regalia and his tribe’s history and heritage.

“I started learning more about traditional ways when I became a Tribal Council member in 2006,” Stuck says.

His grandfather was the product of the government-run boarding schools and became a Christian evangelist who was proud of who he was and where he came from, but never talked about his boarding school experience.

Simms had similar experiences with her grandfather, a full-blooded Odawa. He never talked about the language and culture with his son, Simms’s father.

“My grandfather said ‘Don’t trust the government’. My parents and grandparents were all Christians and I don’t think they had an understanding of how to put Christianity and the Native American culture together,” Simms says. “I’m still struggling with that. “

Isaac says many tribal members, like Stuck and Simms’s grandfathers, were made to feel ashamed of who they were by the way they were treated during their time at boarding schools. The schools were designed to assimilate them into the White man’s culture. She says this left them with feelings, including a distrust of the federal government, that they passed down to their children which her generation and subsequent generations will change.

“We identify ourselves as cycle breakers. Our goal is to bear that burden felt by previous generations for the generations coming after us so that they don’t have to deal with it,” Isaac says. “This is important for our next generations of kids coming through. It develops citizenry and helps our citizens to be more informed. Tribal history is everybody’s history and the original history of the land we live on.”