National Day of Racial Healing in Kalamazoo examines healing and resistance

At the recent National Day of Healing in Kalamazoo, community leaders explored the truths that can lead to healing and transformation.

(Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include photos of other aspects of the National Day of Racial Healing in Kalamazoo.)

Kalamazoo panelists speaking on the 5th annual National Day of Racial Healing sounded exhausted — but not defeated — by the past year.

It was a year of Black Lives Matter, police confrontations, protests, white supremacists marching, an epidemic of shootings and killings, and the ever-present hindrances of the pandemic.

But they also sounded determined, and illuminated signs of hope and change, such as progress in the area of local housing, and people stepping up to provide help in spite of COVID.

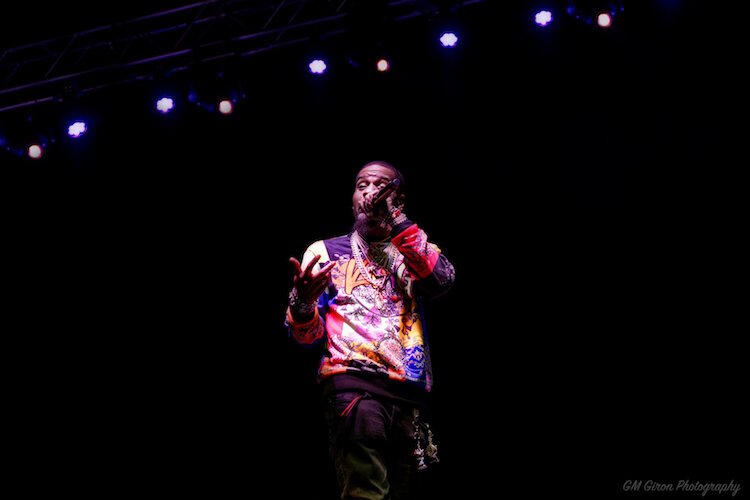

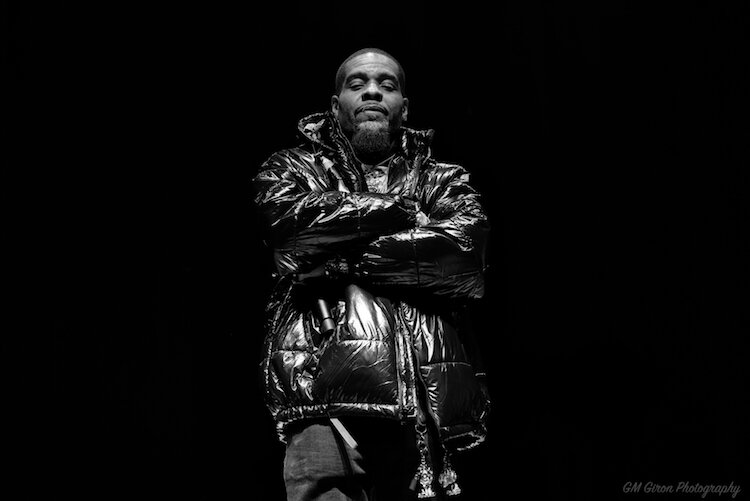

They spoke Jan. 19 from the State Theatre stage, a streamed and socially-distanced event.

The National Day of Racial Healing, part of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation, took place during what felt like a tipping point.

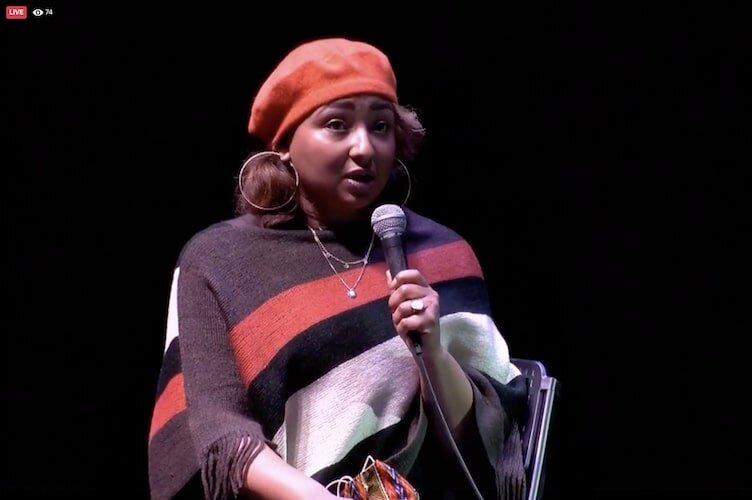

Sholanna Lewis, director of TRHT Kalamazoo, says the premise to “lead with the truth, in order to heal, in order to transform, is a profound one, is a unique one.”

This day should be a holiday, taking place after Martin Luther King Day, she says in her introductory remarks at the State.

They’ve been working with the Governor’s office to get it recognized statewide. The day’s events now take place in Kalamazoo, Battle Creek, Flint, Lansing, as well as other cities outside the state.

It should be a holiday, she says, because, “We always looked at this as a celebration. Why? Because we know we’re not healed yet. We know that we have so far to go. But we also know that if we don’t practice joy, if we don’t celebrate, we will not get there.”

The day is a “bittersweet” one this year, Lewis says. “So much has happened, it has been truly devastating, so many things have happened that are ugly and have ripped us apart.”

She mentions that the day occasionally takes place before a presidential inauguration. In 2017, Second Wave attended that year’s Day of Racial Healing event, at the time of the Trump inauguration.

When asked then about the beginning of that administration, TRHT speaker Jacob Piney-Johnson exclaimed, “Woo! We’ll see how that goes.”

For 2021, the Day of Racial Healing was on the eve of the Biden presidential inauguration where for the first time in an inaugural address an incoming president mentioned both “white supremacy” and “systemic racism” as problems to be dealt with.

Healing and Resistance

Moderator Lilly Mazzone asks the panel at the State Theatre about what healing and resistance meant to them in 2020 Kalamazoo.

Vice Mayor Patrice Griffin says that healing for her is “just accepting the fact that there’s only so much I can do.”

But resistance for her means “resisting the norms that we had been under for many years…. We already knew what was going on, (now we’re) resisting the idea that there’s nothing we can do about it.”

Maricela Alcala, chief executive officer of Gryphon Place, says the year put a big strain on the non-profit’s crisis services. Resistance for her was to “struggle to keep up the work when we had to work even harder and people were getting sick — not necessarily from COVID, we were just getting sick and we were getting tired. And our systems and our structures were just falling apart,” she says. “It was exhausting.”

Stephanie Hoffman, executive director of Open Doors Kalamazoo, says that she’s been resisting “the notion that people were in predicaments because they wanted to be there.” She felt this was an attitude, “particularly towards people of color” that “if we wait long enough, they’ll quit.”

Hoffman continues, “Resisting that is to say ‘No!’ Let’s get this done.” But “on a personal level, resisting that feeling that we have to solve it right now! Everything was so urgent in 2020…. Let’s let this happen organically. Still put that energy of love, empathy, and compassion out there, but we don’t have to have all the answers at this moment.”

J. Kyon, ERACCE trainer/organizer, co-chair of ARTT (Anti-Racism Transformation Team), says the past year “taught us a lot about grief.” And that “we know there are folks who systematically don’t have the opportunity to resist.”

But in the face of that grief, Kyon says “community virtual aid” came about “almost overnight” at the start of the pandemic.

Marshall Kilgore, director of advocacy of Out Front Kalamazoo and first vice-chair of the Kalamazoo Democratic Party says that “one of my healing practices is to know intentionally where the wound and hurt is.”

For Kilgore, resistance “came down to understanding crisis.” The year 2020 “was an insertion boiling point for many of the communities that we all serve. The LGBTQ+ community already had a pandemic going on. We had black trans women of color disappearing, being killed, in crazy numbers before COVID came along. Black men had mistreatment by police before COVID came along. And our communities needed housing, like the vice mayor said, before COVID came along.”

Kilgore continues, “And then COVID showed us, you know what, it’s time to get our game face on. Because we have to do the work within the community before stuff like this happens.” The pandemic “heightened that pain and tension we’ve had in our communities.”

Housing progress

Hoffman described her mood swings as the vote count slowly came in for the “Homes For All” millage proposal after Nov. 3.

First, she was “crying, shaking, cursing” as it looked like the proposal was going down. She was then very happy when the vote turned, but “then I was upset because it was a small margin by which we won. But then, God was like, ‘Girl, you got the win — fall back and celebrate!'”

She was so emotional, “because you know we have the resources within our community to change the game for so many people.”

The millage will “bring so many units of housing to our community over an eight-year period.” That plus the city’s passage of the fair housing ordinance means that things are looking up in this area, Hoffman says.

“Those things give me resilience, they give me confidence. I just flex my muscles because I know we’re doing the right thing,” Hoffman says. However, “It’s not one-and-done. We’re going to be healing forever, generations of healing have to happen. But we are starting that work right now…. Take our lessons learned, and we’re going to go back and do it again, be more savvy the next time.”

‘White absurdists‘ in Kalamazoo

Mazzone asks Griffin “what was it like to witness the acts of violence and hatred by — I call them ‘white absurdists,’ some people call them ‘white supremacy,’ these white absurdist groups like the Proud Boys?”

Griffin recalled a time in February when the issue of fair housing was discussed at a city commission meeting. “There were some calls that came through — my mouth was open. I couldn’t believe some of the things that I heard, that people were so freely and comfortably felt to say. And I watched the lack of reaction from peers, from the general community to language that I’ll say is coded,” she says.

“To see the ways people reacted to Proud Boys (who marched in Kalamazoo in August), and to see the lack of reaction, it let me know that there is a complete disconnect still with how we receive hatred and racism and all of these -isms,” Griffin says.

Her questions to them would be, “Why did you come here? How many of you work here amongst us? How many of you are sitting in board rooms every day? That was what I was most interested in.”

“It’s never good to my spirit, it’s never good to my soul to see people put those displays on,” Griffin says. But she’s more interested in finding who is not so blatant with their racism, “because it’s just as hurtful, it’s just as harmful and just as problematic, and something that needs to be addressed the exact same way with as much fever and as much enthusiasm.”

Epidemic of gun violence

Gwendolyn Hooker, advocate for social justice and criminal justice reforms, and founder and director of Helping Other People Exceed (HOPE) Thru Navigation, says that her resistance was against attitudes towards gun violence in Kalamazoo.

There were “80-something gun shootings, 13 — actually 14 — murders in 2020,” she says. Hooker says the attitude from the general community is that “these are just bad people shooting and killing people because this is what they’ve chosen to do.” And that little is done in “actually looking at what are the core reasons and real reasons that people are so mad and so traumatized and so angry that they’re picking up the drugs and picking up the guns and killing each other.”

This is “another health crisis,” Hooker says. “I am extremely disappointed in the lack of response from city officials, stakeholders, philanthropists, with the exception of two… Kalamazoo Community Foundation and the Greater United Way of Battle Creek and Kalamazoo region. Without them actually standing up for the people who’ve been murdered due to gun violence, there would be no light being illuminated on these people at all… (It would be) shoved under a rug and business as usual.”

“I am extremely grateful for people” — Hooker chokes up a bit — “who’ve actually put their money where their mouth is and actually stood behind what’s important to them — equity, education, justice, fair treatment for everybody,” Hooker says.

But some in Kalamazoo seem more performative than active in their support, she feels. “When it was so cool to say ‘Black Lives Matter,’ they got a sign, they put it in their window, they got a yard sign. But when it actually came time to stand on what you said, when the Proud Boys came, when people were burning down my neighborhood, none of those Black Lives Matter petitioners stood up for us. And they’re still not standing up for us.”

Kalamazoo rallied after the Uber killings, the Chain Gang bike group deaths, she points out. “Why isn’t anybody concerned about 85 gun shootings and (14 deaths)? Where is that outcry? Where is the anger? Is it because we’re black people and it’s happening in neighborhoods that aren’t affluent? Because it’s perplexing to me. I literally do not understand.”

When undocumented workers are essential

Juliana Hafner, director of El Concilio, says that the struggle for the Latinx community is how essential workers were held up as being important during the new pandemic, yet many of these are undocumented workers.

“They had to keep going to work, they did not have the privilege of being able to stay at home, they have to work at the greenhouse, they had to keep going to work to keep bringing food home to their table,” Hafner says.

Undocumented workers are given Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers so “they pay taxes, but they don’t qualify to get federal or state funds, like the stimulus check,” she points out.

“Undocumented people are essential, but were not able to get any funding from the government… They do pay the taxes, but they don’t get the help,” Hafner says.

That’s why El Concilio created the M.I. Gente Fund with the Kalamazoo Community Foundation and United Way to help support families and individuals who don’t qualify for government pandemic funding. They were able to give out $200,000 and help over 800 individuals and 300 families so far, she says.

El Concilio teamed with Gryphon Place to not only provide a contact for people needing the fund but to increase support for Latinx people in crisis. Alcala says, after forming the partnership, they’ve been able to staff their crisis lines with Spanish speakers “who’ve lived what it is to be an immigrant, or what it to have come from another country, or understand our culture.”

They’ve also helped as a COVID hotline for Latinx, provided “rumor control” and helped to develop trust, Alcala says. “They’re going to talk to somebody that’s going to understand them, not only linguistically, but are going to understand their culture, their beliefs, their pride.”

Ally to accomplice

Mazzone asks Kyon how to move from being “a performative ally to a true accomplice.”

“A way to move past performative allyship is to not get stuck in guilt and self-righteousness. And I’m saying this as an Asian-American person,” Kyon says.

“It’s okay to feel guilt, it’s okay to feel self-righteousness. But we cannot stay there,” Kyon continues. “That’s how people end up individually competing and unintentionally harming each other.”

Kyon finds not competition, but situations where people in Kalamazoo are doing the same anti-racist work. “So, I never work alone, and that’s a good way to keep myself accountable, instead of performing.”

Another way to move past being performative is to learn from mistakes, Kyon says. “I think performative people stay in those spaces because they’re afraid to make mistakes. Even though perfection is not real. So, please make responsible mistakes, learn from it, and then we need to move on, because racism is a life or death situation.”