New Kalamazoo Lyceum continues an old tradition of learning together in friendship

To bring back a tradition of neighbors gathering face-to-face, to discuss without the divisiveness that seems to have been born, in part, out of social media, a new Lyceum Movement has begun. Also called “A School for Community Life,” lyceums are happening in various towns in Iowa and Minnesota, and now Kalamazoo is a chapter affiliate. The topic of the inaugural Kalamazoo Lyceum was titled, “How is media changing the way we think?” Read on to hear what panel members and attendees had to say.

Participants of the Lyceum Movement of the 1800s like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau might’ve been dazed and bewildered at the subject of Kalamazoo’s first 21st century Lyceum: The role of algorithms in social media in the degradation of the traditional news media, and the devolution of social discourse in general.

But they’d get the functioning of the lyceum itself, as a gathering of citizens discussing important topics of the day.

On Jan. 28, a Saturday afternoon, over 65 people packed into the Crawlspace Comedy Theatre at the KNAC Building for the Kalamazoo Lyceum’s talk on “How is media changing the way we think?”

Former Kalamazoo Gazette/MLive journalist Linda Mah and former WMUK general manager Gordon Bolar spoke on social media’s influence on their professions. Kalamazoo Lyceum host and founder Matthew Miller moderated.

Before we get into the thorny topic of algorithms and newspapers, a brief history of the Lyceum: In the early 1800s, New Englanders began hosting lectures to help bring education to citizens of small towns, with the idea that democracy depended on a well-informed population. It became the Lyceum Movement and brought the likes of Emerson, Thoreau, Mark Twain, Fredrick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and others to discuss the issues of the day at town lyceums. And as fitting for democracy, citizens were invited to be part of the discussion.

There was a Kalamazoo Lyceum in the 1830s, Miller says, where the hot topics were: Should Michigan become a state? Should we fight Ohio over where the border falls at Toledo? The abolition of slavery and women’s right to vote were also discussed.

Lyceums vanished as mass media grew. Daily newspapers, radio, and TV brought the world and ideas directly to people’s homes in the 20th century.

And then, the internet arrived. Just as the Lyceum seemed a quaint old custom in the 20th century, reading the daily newspaper may seem a quaint old custom to many today.

To bring back a tradition of neighbors gathering face-to-face, to discuss without the divisiveness that seems to have been born, in part, out of social media, a new Lyceum Movement has begun. The site calls it “A School for Community Life.” It shows lyceums happening in various towns in Iowa and Minnesota, and now Kalamazoo is a chapter affiliate.

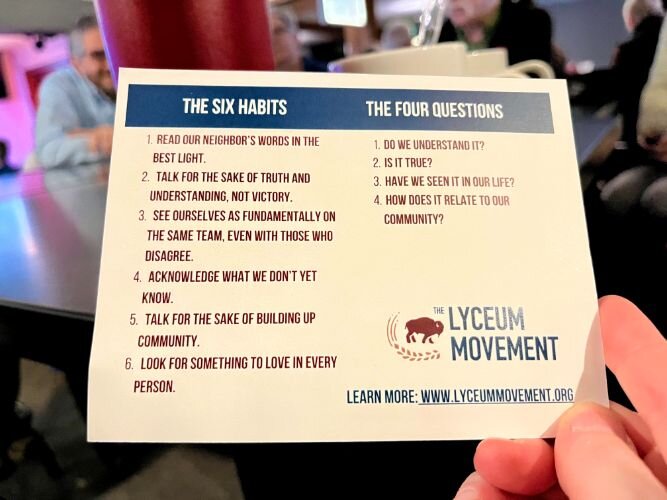

Miller writes, “The Lyceum Movement’s mission is to, ‘build meaningful communities by providing a space for neighbors to learn together in friendship.’ They support folks — like myself — interested in the Lyceum model by helping create chapters in their communities. They provide support with creation, strategy, and programming materials, while still giving the majority of autonomy to each chapter director. “

Gamification of life

COVID forced us to be isolated, but, Miller says in his introduction at the new Lyceum, “the times are asking us to be isolated, to be able to get everything that we need and stay inside, shelter within our own echo chambers.”

Miller quoted journalist and commentator Ezra Klein, who called social media “the gamification of life,” where people share ideas, life moments, cat photos, and political viewpoints, and then get rewarded with game-like points that are stand-ins for human interaction. One might get likes, one might get re-posted, and one might even win the game and go viral.

He asked the panelists if this gamification had any impact on their lives.

Bolar replied that in his view, “As humans, we’re hardwired to search for the truth. And for some of us, that’s what our life is. Truth in terms of someone who’s an expert, truth in terms of verification of our identity, truth in terms of bonding with others in a tribe or a group or a Facebook page, that’s the kind of truth I see us looking for. And inevitably, certainly, in the social media, I never see it delivering that for me.”

When on social media — Bolar said earlier he’s only on Facebook, and “not proud of it” — “I’m inevitably disappointed. And I think maybe other people are, too.”

Mah says, “I don’t see social media as providing much in the way of truth… It is that gamification… People love getting the hearts and the retweets and having thousands of followers.”

She continues, “When we first started using Facebook at the Gazette, everybody wanted to be my friend. Sure, everybody’s my friend! In terms of sharing stories, you wanted to have as many followers as possible. So I had tons of people,” she says.

“Now, I rarely add a new friend, unless it’s somebody I actually know, just because it doesn’t serve my purposes. I don’t need to see those posts anymore. As a reporter, I needed to have people liking and sharing my stories, right?”

When Mah left the Kalamazoo Gazette, she became a communications specialist for the Kalamazoo Public Schools. For the past year, she’s also been writing as a journalist for NowKalamazoo.

(Full disclosure: Mark Wedel was a long-time arts and entertainment correspondent for the Kalamazoo Gazette from 1992 until 2015. Many of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s editors and journalists were staff/freelancers for the Gazette.)

Mah went into how social media changed what had been Kalamazoo’s daily paper since 1833.

“I think gamification of the news cycle is something I witnessed when the Kalamazoo Gazette went from a print product to an online product — just because it changed the way we covered the news,” she says.

“And people might disagree, they might say, oh no, we’re all about choosing the best stories and the most important stories. Ideally, yes, but when, as a reporter, you used to make decisions about what mattered as a story, what mattered to the community, is this an important story, do people need to know this? And that changed to, how many clicks is this story going to get?”

She continues, “(A story) only had value if it was getting clicks for the newspaper. And for the reporter, it only had value if it was getting clicks for me. Because at the end of the year, my evaluation was, how many people liked my stories? How many people shared my stories? And that fundamentally changes how the newspaper covers the community. If a story was popular today, at your news meeting it’ll be, how can we follow this up? What story can you do tomorrow that feeds off of this? And it goes for as long as possible until the story peters out.”

“It changed the nature of the newspaper and how we covered things,” she says.

‘Cooked meat’

Bolar, who worked in public media for 22 years, says that the pressure to get advertisers wasn’t the same as it was for for-profit news media.

He looked back to a public radio conference he attended around 2000, where the question was asked of a speaker in the industry, “Could you describe this whole digital transformation that’s coming in terms of our news, in just a few words?”

The speaker said, “I can describe it in two words: Cooked meat.”

Bolar elaborates, “The digestive system of the caveman changed with fire, cooking meat.” News in digital form changed because we digested it differently.

“Online, you could go back and revisit a story, and you could take your time in digesting it.”

Mah says that the big change she saw was her publication’s new demand for speed first, and accuracy later.

She gives a frustrated laugh. “As a journalist, I’d like to think that we’d operated with a duty to being reliable and truthful.”

With the advent of online news and increasing dependency on the internet, newspapers were reeling. The bottom was falling out of local journalism and print media was struggling to find its footing. When the Gazette shifted its focus from paper to online, at “one of those first meetings, they said, ‘listen, the main thing is to be first. You hear about that story, get that story out there. If there’s a mistake, we can fix it later,'” says Mah.

“I remember coming out of that meeting, and all of the reporters, we looked at each other, and were like, ‘Did they just say, don’t worry if it’s right?'”

Mah continues, “Maybe we didn’t always get it right, but we always tried to get it right. The media changed in a way that became less important. It became more important to be first.”

Bolar says the move online also led to an “expectation of engagement, and things become a two-way street. Oh, they can talk back, can’t they? Now, maybe you had to hire and pay someone to do community engagement if you had the money for that.”

As the paper went online, Mah was tasked with online engagement, primarily to keep the comments civil. But that task was very challenging because few posters respected the warnings.

“Oh, well this is really working well,” Mah drily says. Now, few publications have open comment sections, she points out.

Bolar says that WMUK had the same issues when it allowed comments on news stories. “Pretty soon it became obvious that this was more than a full-time job to moderate… Being licensed to Western Michigan University, there are certain threatening things that you want to weed out, that you’ve got to be on top of.” The station didn’t have staff to moderate comments, so the comments had to be removed.

As a non-commercial station, “we didn’t have advertisements, we weren’t measuring clicks so much.” Without the pressure to be first and to get online engagement, “We had much more of an emphasis on accuracy in the story than it appears you said you had,” Bolar says.

George Santos

Miller asks the two how this pressure to get stories out first affects their audience and community.

Bolar says, “One of the mantras we did hear in our newsroom was ‘this is a sacred trust with the public.’ And once you lose it, it’s really difficult to get it back, so let’s not lose that.”

Mah says, “People don’t trust the media anymore. Which is unfortunate. I’m not sure how we build back that trust because it takes a different kind of reporting, I think. That’s not to say I don’t think journalists try, I think they do. I still believe in journalism, it’s an important job, and I think they do their best to provide accurate information. But it’s harder.”

“I will also say, George Santos.” Mah pauses as the audience laughs at the name of the U.S. representative elected last November, who was later found to have lied about his life, from his schooling to his religion. News sources that reported on his falsehoods did so only after his election. “How did nobody… did nobody say, ‘hmm, maybe we should check this?'” Mah says.

She blames diminished newspapers. “For newspapers, they just don’t have the staff that they used to.”

When Mah started at the Gazette in the late-80s, “we had this huge newsroom with dozens of reporters, dozens of editors, five or six photographers….”

Papers made staff cuts as they went online, so remaining journalists had to do extra work that photographers and editors did while attempting to cover more beats and more of their region, she says.

“And then you get a mistake in, and people in the comments are like, ‘don’t you have editors anymore?’ Well, no.”

The algorithm

Mah and Bolar agreed that the changes in local news media make it difficult for citizens to get basic information about their community.

Mah notes that she has to put work in, as a citizen to search for credible info about the local community, events, elections, etc. “People have to be more diligent to make sure that they get accurate information.”

In her work with the KPS, she has to try to reach parents through Twitter, Facebook, and the schools’ print publication Excelsior.

“You want to get a message out there, and it’s just harder,” she says. “Even if the city commission or county government wants to get information out there, I think that’s harder. What format do you use to make sure you’re reaching all the citizens?”

To spread basic community info online, “people have to share it and to like it because that changes the algorithm. It is all interconnected.”

The algorithm — basically, the guts of most social media that look at what a user likes, which then tries to feed the user more of what they like to keep them online — doesn’t seem to favor dry but important local information.

Mah says she often sees friends and family share more interesting, yet provably false, items online. She has to be the one to say, “Mom, I’m not sure this is what you think it is.”

Local media re-boot

Miller comments that the situation for news media “seems really gloomy.”

Asked for good news about the news and social discourse, Bolar responds with “one ray of hope,” StoryCorps, recordings where ordinary people talk about their lives that are aired on National Public Radio stations like WMUK, and its offshoot, One Small Step.

One Small Step features, “Two people of diverse political viewpoints…. getting together and putting all of those code words, epithets, insults aside and talking about what values they shared, face to face.”

Bolar says, “There’s no substitute for sitting down and sharing your values, sharing who you are. Because right now, engagement is just the illusion of engagement (in social media)… You don’t know who you’re talking to. Are you talking to a real person? An avatar? And then there’s your own identity. What are you sharing? Does that really represent you, or is that some fake shilled-up thing that you projected out there to get likes, clicks, and shares?”

Mah says, “My ray of hope is, maybe we’re having a little re-boot. Locally we have things like Second Wave Media, NowKalamazoo. Those are online, but they have some seasoned journalists, and they’re out there doing local stories, trying to build audiences. It’s very interesting to see start-up media, to see efforts to redefine journalism and the kinds of stories that they want to cover. I think the emphasis is on building community with the stories they choose to tell. So that makes me hopeful, to see those media growing.”

She also points to “an awareness of the need to help young people understand the media and their relationship to it.”

The Kalamazoo Valley Museum has an exhibit, Wonder Media: Ask the Questions for youth on “how do you look at the media, how do you judge what’s true, how do you interact with it, what is your responsibility in the process. I think that that is really valuable,” she says.

Also, “in the schools, I see teachers working to help kids understand their relationship with technology. What does it mean when you’re on your phone all the time, do you need to put it down, do you need to engage with people face to face? That sort of education will help create a new, educated consumer. That gives me hope, too.”

For participant response to the first Kalamazoo Lyceum, please see the sidebar.

The date for the next Kalamazoo Lyceum is TBA but is expected to be mid-to-late March.

The March Lyceum will discuss the question, “Do we have culture?” Miller says. “We use the word “Culture” in all kinds of ways. We talk about pop culture, workplace culture, political culture, culture war, and so much more. But what about the stories, artworks, songs, food, and more that make up our daily life? Do we feel like we have a rich local culture and identity in Kalamazoo? Why or why not? What is it like, and what defines it? This will be an opportunity to hear from local cultural producers and for the community to talk among itself about what our own local culture really is.”

For more information, visit The Kalamazoo Lyceum Facebook page.