The likenesses of actual people were part of the inspiration for Kalamazoo sculptor Joshua Diedrich’s latest public artwork located outside Bronson Methodist Children’s Hospital. “It grants legitimacy to the people,” says Diedrich when asked why he made that choice.

The artist, whose first memory is holding a finished sculpture in his hand, is a classically trained figure sculptor. He’s most recently created six life-size figures including five children, a mother, and her infant. All of them are loosely based on photographs submitted by hundreds of individuals, patients, and families who were helped at the hospital in some way. The mother and her infant were the only figures drawn completely from their photographs.

The artwork was unveiled on Tuesday, Aug. 24 at the hospital’s Eastern entrance on the corner of Vine and Jasper streets in Kalamazoo. The clear and bright late summer’s day perfectly matched the mood of the crowd as Diedrich unfastened the cords around the deep purple covering, and the fabric fell away to reveal the intertwined greens and blues of the statues.

The artist’s face looked proud as he took in the reactions of the gathering of family, friends, doctors, and patrons standing beside the artwork almost twice as tall as many there. This piece took Diedrich 18 months to complete and he worked on it mostly during the statewide shut down due to the Covid-19 pandemic, labor on the artwork starting in February of 2020.

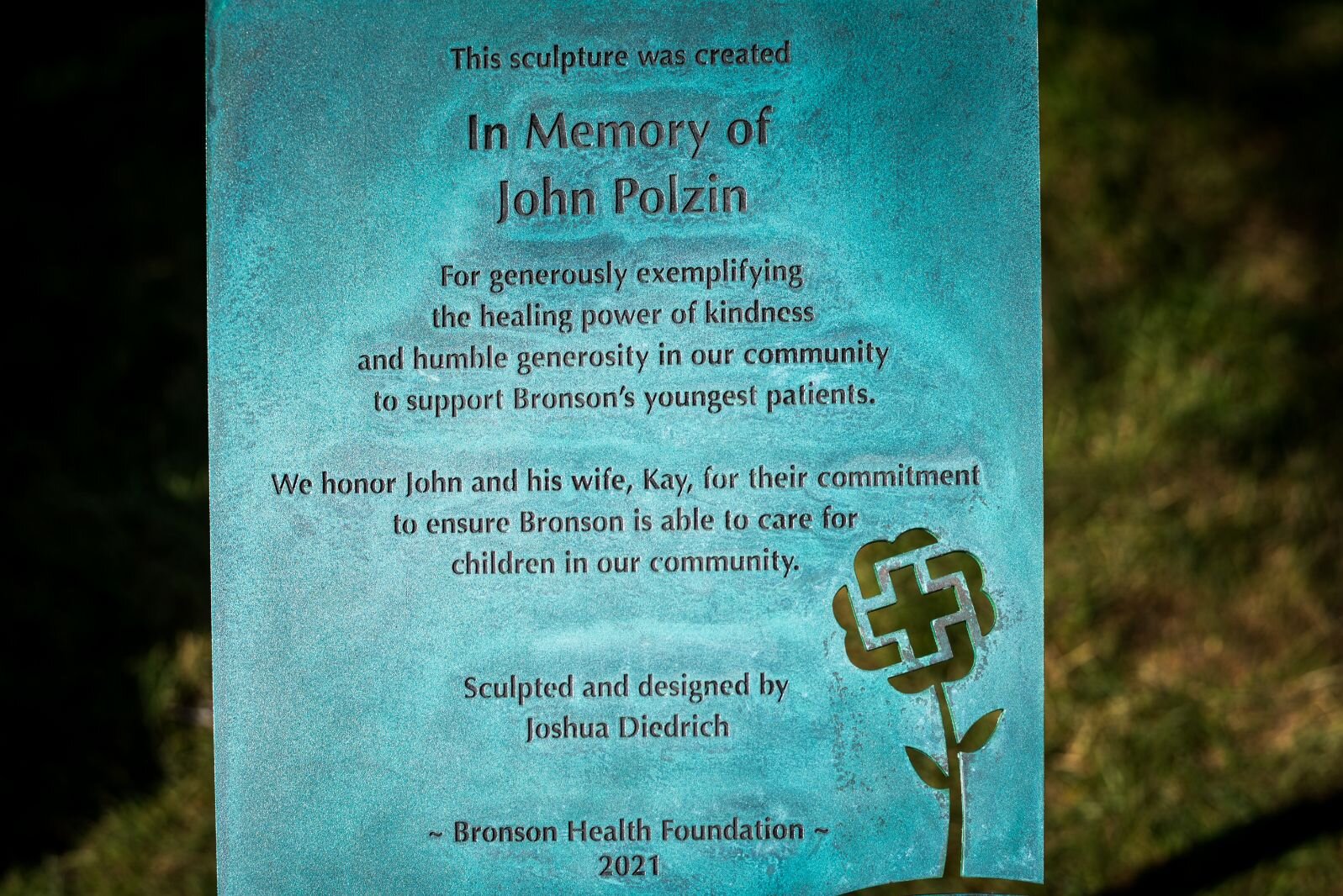

The public art piece was funded through the Bronson Health Foundation, predominately by the John Polzin family. Polzin was a leader with the Bronson Health Foundation and the sculpture was created as a way to eulogize Polzin’s exemplary “healing power of kindness and humble generosity in our community to support Bronson’s youngest patients,” which is what is engraved on the plaque near the piece.

Diedrich says that “every piece of public art needs a champion,” someone who will put in the emotional and physical effort in getting the idea of the piece to blossom into a realized project. The Polzin family championed this artwork. The proposal for the piece was made shortly after Polzin’s passing in May of 2017, and after considering several different sculptors, Diedrich was put on retainer in April 2019.

After receiving the portraits submitted to Bronson to be used as inspiration for the bronze figures, Diedrich decided he needed to stay true to his own personal philosophy on creating a public sculpture. “Unless the piece is meant as a portrait, I don’t want to be hemmed in by one person to sculpt their likeness…”

When it comes to a piece that will “be seen by thousands of people, there needs to be randomness in the selection process so that no-one feels too much the work is theirs–it belongs to whoever sees it.”

The only exceptions to this belief were the mother and child. Every other figure combines attributes of the many different faces and bodies portrayed in the submitted photographs. Diedrich thought it important to include the Native American woman and her child in the piece largely because he asked them to be included in the sculpture, not the other way around.

To learn more on the importance of public art, Second Wave spoke with Kalamazoo multi-media artist, and co-owner of Dream Scene Creative Placemaking and Mural Collaborative Anna Lee Roeder. She agrees there is a need for public art to be relatable and approachable. Roeder says, “Public art is best when it is accessible—when someone doesn’t need to enter an institution to experience it.”

Both Deidrich and Roeder also touched on the need for the piece to be exciting in some way, and in the world we live in, public access to beautiful artwork is exciting in itself. The sculpture created by Deidrich using the lost wax method of bronze casting combined with touches of the 3-D printing program Zbrush is a perfect example of how practices several thousands of years old can be translated into something enjoyable and exciting to the modern everyday person.

Roeder also commented on how public spaces in Kalamazoo have immense potential as completely open venues for residents and passers-by to have an experience of art and to see themselves in the art. Roeder’s core belief about public art “is that it creates conversation, and activates a public space.”

As someone who was an inpatient at a hospital for several extended stays as a child, Diedrich agrees. “It’s my hope that every child going into the hospital can find themselves somewhere in the piece,” he says. A hospital is typically viewed as somewhere a lot of people would rather not end up, and Roeder says that the statue “gives a point of reflection” around a place that is there for people who might be experiencing trouble.

In the world we live in, where the arts are routinely being slashed from communities and schools, public art especially holds a significant and important place. People deserve to experience artwork without having to pay for it, and without having to enter a space made for or by “others.”

Diedrich’s work occupies a special area of art because sculpture by nature is historically something made public to honor a person or event. As both Diedrich and Roeder spoke with Second Wave, they talked of how public art brings people into their surroundings.

Bronson Children’s Hospital is somewhere numerous folks go repeatedly, and one of the best things about artwork is that it leaves the door open, if you will. It could be the 20th time someone walks by it, and the artwork could remind them of something or spark a new thought, or the person may even notice a detail they hadn’t seen before. Diedrich’s artwork will bring people more fully into their surroundings so they can more fully experience and enjoy the space they occupy.

Diedrich also has participated in one of the most public of public art experiences as the regional representative for the Burning Man Organization based in San Francisco, Calif. The 2021 Burning Man Festival took place in the Black Rock Desert, 120 miles north of Reno, Nevada, and for the duration of the festival, the make-shift city becomes one of the most populated in the state.

Diedrich explained that the festival relies on 10 core principles, the first being Radical Inclusion. Participation is a huge part of the Burning Man Festival, and the way the artwork is created and destroyed changed Diedrich’s perspective. “The art has to be awesome in some way, where people want to be a part of it,” says Diedrich.

When asked about why public art is important for Kalamazoo specifically, Diedrich answered, “People don’t see themselves in these old dusty statues of white men and they want to see themselves.” It is important to consider what the society’s values are, and what the meanings of that space are when creating the piece.

On the front page of the Bronson Children’s Hospital website, it states, “They are dedicated solely to caring for children…”, which means every child.

Diedrich’s sculpture shows that with a lot of very hard work done in almost complete isolation due to the pandemic, and with a huge amount of community involvement at the beginning, the result can be something astoundingly beautiful, and subjective. Diedrich’s sculpture, perhaps most importantly, also shows the resiliency of children.

Every child that passes Diedrich’s sculpture on the way into the hospital can see that they may leave there laughing or held tightly. They will see themselves, and be drawn into the artwork and their surroundings in a way that was not possible before the public art was installed.

If you would like to see the piece yourself, it is on display 24 hours a day year-round outside the Bronson Children’s Hospital located in the Vine neighborhood.