Learn about how to buy the book or order an advance copy here.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Battle Creek series.

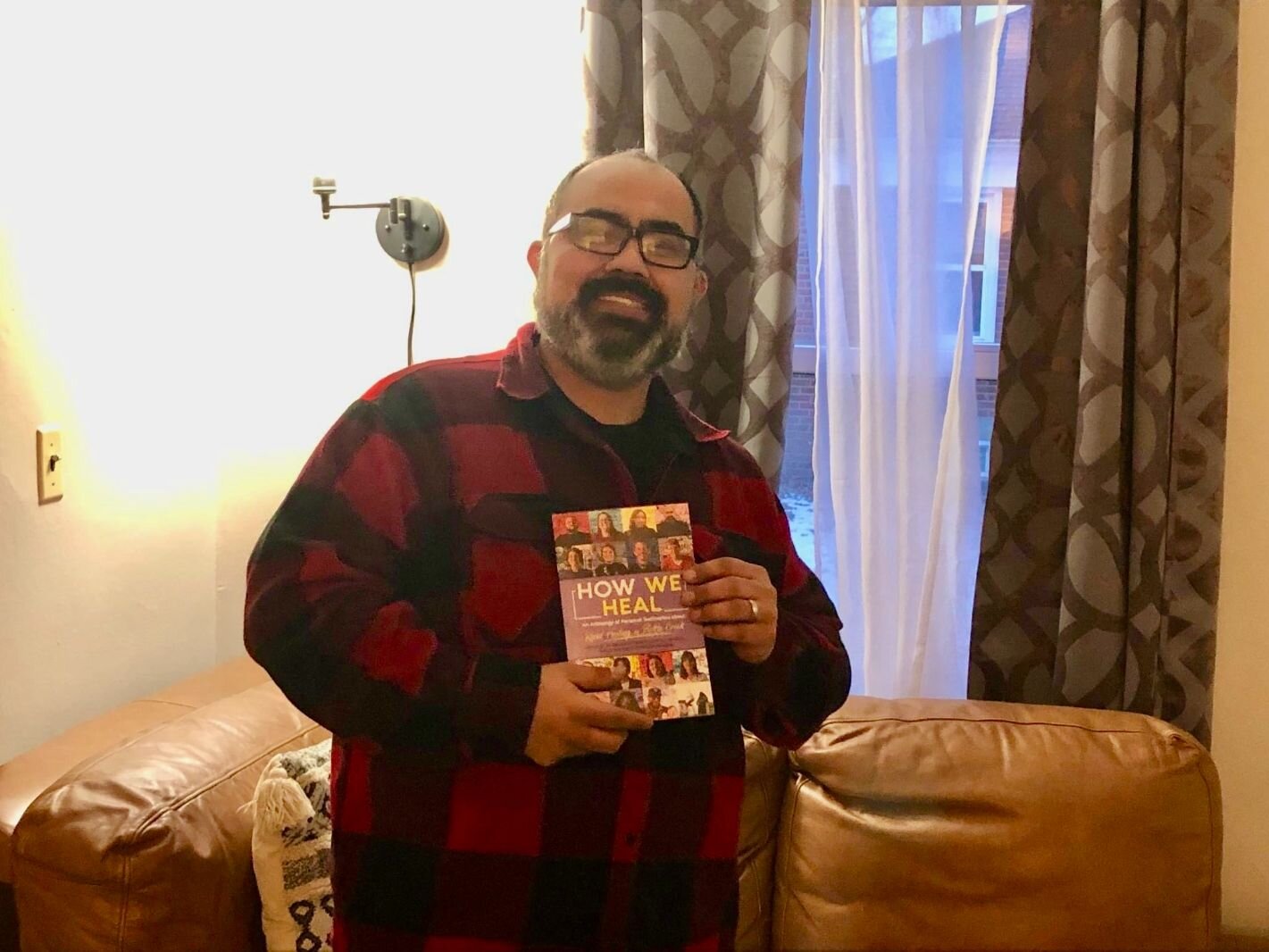

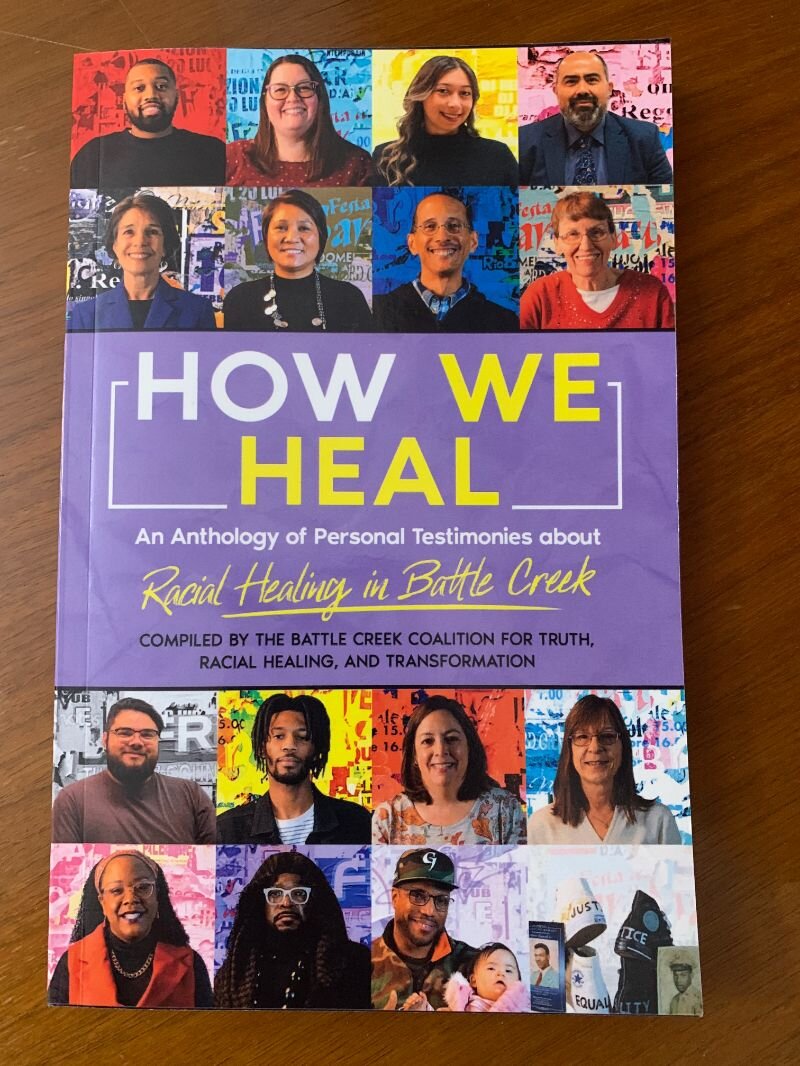

Par Mawi’s role in Willard Library’s circulation department gives her plenty of opportunities to deal with books focused on other people’s stories. On Tuesday, Jan 25 during a Facebook Live event she will be one of several Battle Creek residents sharing their own stories captured for posterity in a book titled “How We Heal: An Anthology of Personal Testimonies About Racial Healing in Battle Creek”.

The idea for the book came about after the Battle Creek Coalition of TRHT (Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation) community leadership team decided in 2021 to include more virtual events and different types of activities as a way to observe their annual National Day of Racial Healing in the community in the midst of the pandemic.

It was originally framed as racial healing love letters to Battle Creek at the suggestion of L.E. Johnson II, Ph.D., Chief Diversity Officer and Director of Engagement for the Southwestern Michigan Urban League and member of the TRHT community leadership team.

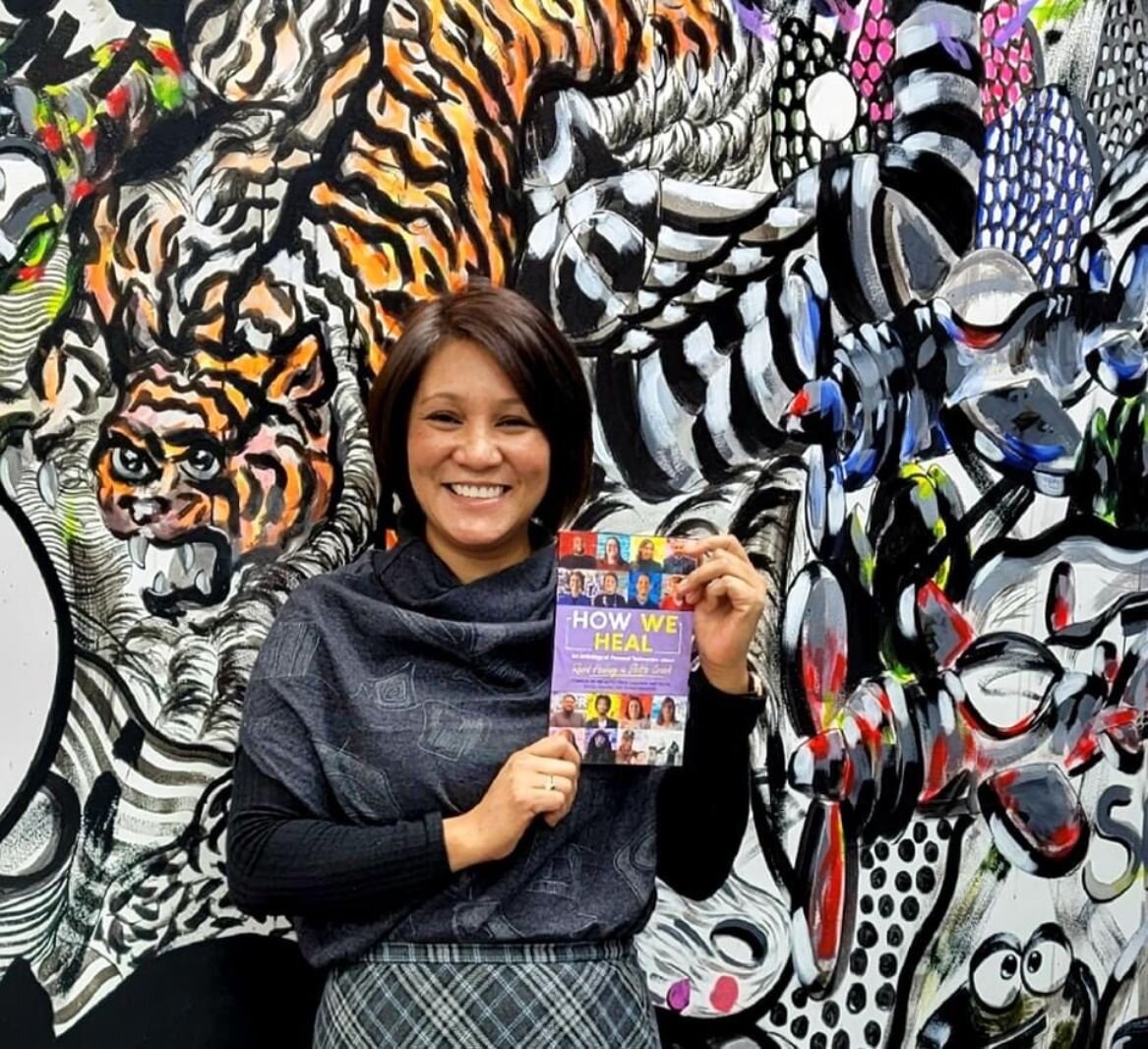

“The idea was to show how we emphasize love and abundance in doing our work,” says Rosemary Linares, co-coordinator for TRHT’s Battle Creek Coalition and a Principal of Cross Movement Social Justice Consulting based in AnnArbor. “It evolved as we saw what kinds of submissions we were getting.”

These submissions, in the form of poems, short stories, and interviews contain personal reflections, some very deep, capturing a specific memory of what it looks like to be part of different races, ethnicity or culture in Battle Creek. Members of the city’s African American, Burmese, Latinx, and White communities are represented in the book.

Mawi says she agreed to submit her story because she wants people to know how her journey from Burma to the United States shaped her into who she is now.

As a people, she says, “We have a lot of untold stories and being here in the U.S. is not easy for us. There are a lot of language problems and everything needs to be learned like the education and financial systems,” Mawi says. “Our culture is different. We don’t think about the past. We have to survive and forget what’s happening. It was so hard for me to find a place to talk about what I’ve been through, especially sexual abuse, which is something that’s been inside of me forever.”

Linares says she was moved by Mawi’s eloquence in telling her story and the bravery she displayed as she describes her journey to Battle Creek and the challenges and obstacles she had to overcome.

“Her spirit remains steadfast and I see her as a warrior,” Linares says.

In 2007, Mawi and her 18-month-old daughter were among 100 Burmese refugees on a boat who were fleeing their homeland in search of a better life. A fishing boat crashed into their boat in the middle of the sea and killed about 100 passengers, including Mawi’s daughter whose body was never recovered. The surviving 38 passengers, including Mawi, were transported to a refugee camp in Malaysia.

“I lived in that refugee camp for more than three years,” she says.

With the exception of a group of church members, Mawi says, “No one was helping us. I had to find a job. There were a lot of people there and we only had three or four lawyers to interview and process us so we could come to another country. I had seven interviews. There were so many processes to go through.”

While at the camp she became pregnant with a son, now 13. They originally were sent to Texas, but after one week there, Mawi says, “I knew I’d never survive living there.”

In 2011, they came to Battle Creek with the help of the Thwanghmung family, among the earliest Burmese refugees to settle in Battle Creek. They were sponsored by members of Battle Creek’s First Baptist Church more than 30 years ago.

Mawi, who was a lawyer in Burma, says the story she tells is “very painful” but also an important process for her in her own healing journey. She says she’s confident that people who read the book, including some of her co-workers, may not realize the challenges she faced.

From a broader perspective, she says the poems and stories shared by her co-contributors may help other people to realize the importance of knowing other people’s experiences and increase an understanding of what it’s like to identify as a member of the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) community.

“It’s important to share your own experiences publicly,” Mawi says. “It’s more important to try to understand people through their own personal experiences. There’s a huge learning process in the United States because everybody is coming from other countries and we’re here together and everyone has their own problems to deal with.”

Linares says part of the foundational work of TRHT is to create spaces for racial healing. She says one of the more common ways used are Healing Circles, which are virtual during the pandemic. She says these circles inspire participants to reflect, share and bear witness to shared pain and joy.

“You can ever recreate that moment to have the same people in a room together,” she says. “The book is recreating that for perpetuity. You can almost mimic experiences of being in a racial healing circle because of the 25 contributors. This book is meant to foster opportunities for racial healing and reflection based in community members that are real.”

The courage to be vulnerable

Having read the book before it was made available to the general public, Linares, who identifies as Latinx, says she appreciates each and every entry. Some of them resonate with her own lived experience. Those entries were submitted by Tristan Bredehoft, who identifies as Costa Rican Hispanic/Caucasian in the book and is co-owner of Café Rica, and Michelle Salazar, who identifies as Latinx (Chilena /Colombiana) American and is a Housing Intake Specialist with the City of Battle Creek.

She says Joanne Knox’s story about being a Black child using a “whites only” restroom in Jackson, Miss., during a vacation with her godparents was eye-opening for her. Knox didn’t know she had done anything wrong until she saw her godparent’s reaction.

Linares says the book is “by no means exhaustive of the entire community. We recognize that to publish a personal story calls upon one to be vulnerable and to be willing to take a personal risk. Some people did interviews that weren’t published.

“We had a workshop on how to do oral history and documenting with the Tribe (Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi) and the folks who met with us didn’t want to have their stories captured in that way. We even had some contributors to the book talk directly about the vulnerability and fears that they have but also the ability to embrace it.”

There also were a fair number of people who either started the process of writing or being interviewed who ultimately decided that they didn’t want what they wrote or said to be published.

“The people who stepped forward reflected and were prepared for what this would entail,” Linares says. “I think more people expressed an interest in submitting than actually did. They knew that what they would say can live in perpetuity and that’s daunting. To have this snapshot in time is like a frozen moment. Reflecting during a global pandemic and a global racial uprising is in an incredible, unique time.”

Some of the 25 contributors to the book discussed why they wanted to be a part of the project.

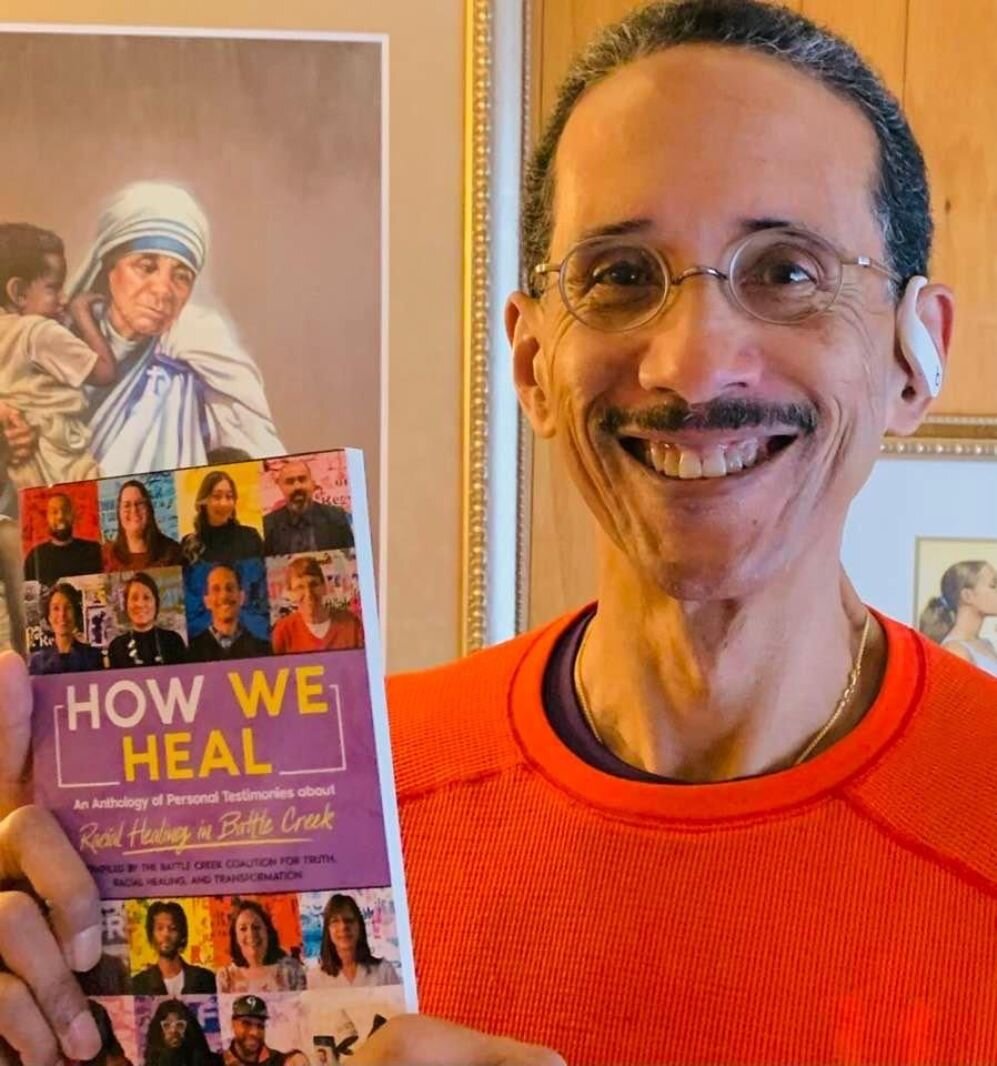

La’Ron Marshall, founder of Vision 21 a life transformation organization, made local headlines in January when he was wrongly arrested on a charge of resisting and obstructing police after two deputies approached him about possible solicitation at Wyndtree Apartments in Springfield, where he used to live.

At the time, Marshall was seeking signatures from residents for a tenant’s association.

He wrote about the arrest for the book. He says the arrest and aftermath put a strain on his relationship with the mother of his daughter. That led to a separation from her and questions from two of his other children who were with him at the time of the arrest. They asked why they still get into trouble even though they try to be good.

“I know firsthand pain, how pain feels and how it’s received and exhibited,” Marshall says. “I’ve been through a lot of pain my entire life. I was incarcerated for 20 years and that’s a whole different level of pain. My father and I were estranged for most of my life and now we talk every day. He’s part of my daughter’s life.”

Marshall has taken that pain and those experiences and is now working nonstop to be a leader and advocate for change. He works with several organizations in various roles including the SHARE Center where he teaches life skills, the local NAACP where he serves on the Legal Re-Dress Committee, and as a member of TRHT’s Community Leadership Team.

“I’m a leader and to be a leader you have to listen to people. You want to hear people’s voices. The pain in their voice matters,” Marshall says. “You have to hear the masses and you have to know how to assess that. This entire book is important. Each individual’s testimony is different and their pain is told in a different way. This is an opportunity for people to see that ‘they’ve been through what I’ve been through’ and they can come out of it. Practice doesn’t make you perfect, it makes you better. The more we practice coming together as a collective and communicate and stop all of this hate and violent mentality, we’ll be better off. The better we become as one.”

Marshall says anything that he can do to accelerate the betterment of everyone is what he will do. He calls the book is a righteous endeavor, a big deal, and something that needed to be done.

“I’m hoping that the naysayers get this book,” he says. “People had to be brave to do this. The individuals who had courage to go through with this are a very important part of the healing process. This lets people know that we’re not alone. We’re all going through it. Let’s go through with it together.”

Victoria Fox-Ramon, a teaching and movement artist, says she wanted to share a little piece of her healing journey with family, friends, and the overall community.

“I think that every person’s healing journey is different and the more we collectively share stories and experiences, the closer we will be to an overall healing of the community,” Fox-Ramon says.

She submitted a poem that highlights her relationships with the people who raised her. She says her culture and identity are “very much tied” to people and landmarks in Battle Creek where she was born and raised and continues to live with her two school-age children.

These relationships, Fox-Ramon says, “are what made me want to write a poem about my healing when it comes to people in Battle Creek and my own community of family and friends.”

She says she hopes the experiences shared in the book will provide “aha” moments for readers. She hopes it leads them to acknowledge that, “We are actually all in the same community. We may not understand that people we know experienced racial trauma or that there could even be racial trauma among us all. We have to recognize and expose the trauma and the damage that’s been done so we can begin to collectively heal.”

Talia Champlin, a local Realtor, says she thinks there is a minority of people who are really trying to engage in racial healing work, but that there’s a bigger group who would do better if they knew better.

“A lot of White people don’t think there’s a problem. What we’re trying to be is a shared community where everyone can flourish so everyone’s voices can be heard.”

Champlin says, “It’s easy for White people and people of economic privilege to think this is a great community where we all have equal opportunities and if you’re not flourishing, it’s your fault. We were brought up to feel that way. We were not educated about how government segregated us from the 1930s on,” Champlin says. “I took Fair Housing workshops each year for 38 years and we were never informed about red-lining.”

She also did not know that Black Realtors weren’t recognized by the National Association of Realtors or allowed to be members of the NAR until 1961 or that realtors would not sell a house to someone who they thought would damage the neighborhood economically by moving in. These ways of thinking were the outgrowth of government programs and choices made by the corporate sector that were not favorable to Black people.

“I’m hoping that people will open their hearts and be willing to be influenced by other people’s experiences,” Champlin says of the book. “If someone comes to this book with an open heart, I don’t see how they could not have their minds changed.”

Katina Mayes, a Community Leadership Team member and Racial Healing Practitioner for TRHT, says she didn’t really see the Battle Creek community having a big issue with race relations until she got deep into her work with TRHT uncovering covert discrimination taking place in many sectors.

“I did not know there was so much discrimination going on, it was like it was undercover,” Mayes says. “Some events that took place in the government and the world started making people more comfortable about who they are not only as Battle Creek as a historical town with racist type of issues but the world this is why this racial healing work is needed all over the world.”

Mayes says she often thinks about stories that her granddaughter shares with her from time to time.

“I never realized how much her young mind turns. We were having an authentic conversation one day. She was about 5-years-old at the time. As we were talking I could see her little wheels turning and she said it wasn’t right that people were treated differently and I had to explain to her that not everyone is treated equally and we need to treat people not based on how they look,” Mayes says.

As a healing practitioner, she says she thinks people are helped the most when they know they aren’t the only ones going through difficult times.

“I’m hoping that this book can give people some solace,” she says. “Sometimes people have a prayer book or a meditation book. Maybe this book of how we heal can give someone some type of solace. My mentality is all-inclusiveness. We want to see everyone in this book. We did not want to exclude anybody. No matter what race you were or how you identified if you had a story we wanted to hear it.”

Linares says TRHT was intentional in ensuring that the book presents a variety of different perspectives which is part of the way to disrupt the dominant conversation of Black and White.

“We did an effective job of representing what Battle Creek looks like. It also highlights that we’re all impacted by racism including white folks,” Linares says. “I’m always looking for multiple perspectives and analysis that goes beyond binary. We need to have those conversations as well conversations about anti-Black racism that impacts other communities.”

The book, she says, is a start and there is still a lot of work to be done.

“It’s going to take our lifetimes to do this work and foster the transformation our country so desperately needs,” she says. “I hope this book will ignite an interest and serve as an entry point because these are our neighbors. All of us are impacted by racism and we all need to figure out what we can do to change that. These are people and they are us. We need everyone.”

Learn about how to buy the book or order an advance copy here.