Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

"We prefer to go to the camps. We do the cooking. We'll put on hiking boots, and we'll trek off wherever we need to trek off to, to find our folks."

Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s series on solutions to homelessness. It is made possible by a coalition of funders including the City of Kalamazoo, Kalamazoo County, the ENNA Foundation, and LISC.When members of United for the Unsheltered bring food to people hidden away somewhere in the margins of the community, the volunteers put a bit on their own plates and share the meal.

U4U has been working to help Kalamazoo’s homeless people since February when it started as a handful of people. They now have 175 members in their Facebook group. Most donate needed items, but, “We have three dozen or so volunteers who are just very, very active,” group president Megan Giambrone says, “who really just keep the meal-train moving, keep the meals going out, keep supplies going to the camps.”

Second Wave met one member, Meg Forrest, who specializes in helping people through the long process of getting housing vouchers and a place to live.

Forrest is “outreach support/pet care,” and is a wiz at navigating the voucher system, Giambrone and vice president Shari Boone say.

“We prefer to go to the camps. We do the cooking,” Giambrone says. “We’ll put on hiking boots, and we’ll trek off wherever we need to trek off to, to find our folks.”

“We’ll sit and eat with them, too,” Giambrone says. “That’s been really kind of a big thing in building our relationships. They know if they’re eating it, my husband and I ate it that night, too. I would never serve anything I would not want to eat.”

Treating someone in a dire situation as an equal is a key stance in social work, she adds — Boone is retired from a 35-year career in that field. “There’s something about food, and just being able to share that, that makes people feel a little more trustworthy. “

Giambrone says, “It’s kind of a family thing. That’s what families do, you sit down and eat. They’ve all kind of become extended family members.”

Sometimes Boone sees well-dressed volunteers drop off food or supplies, and then leave. She shows up at sites in her Pink Floyd sweatshirt — Boone proudly says she’d been mistaken for homeless when she’d arrived at shelters around town — and will work to build relationships with those who need help. She wants to convey the message that “it’s not like I’m so much better than you.”

Seeing the invisible

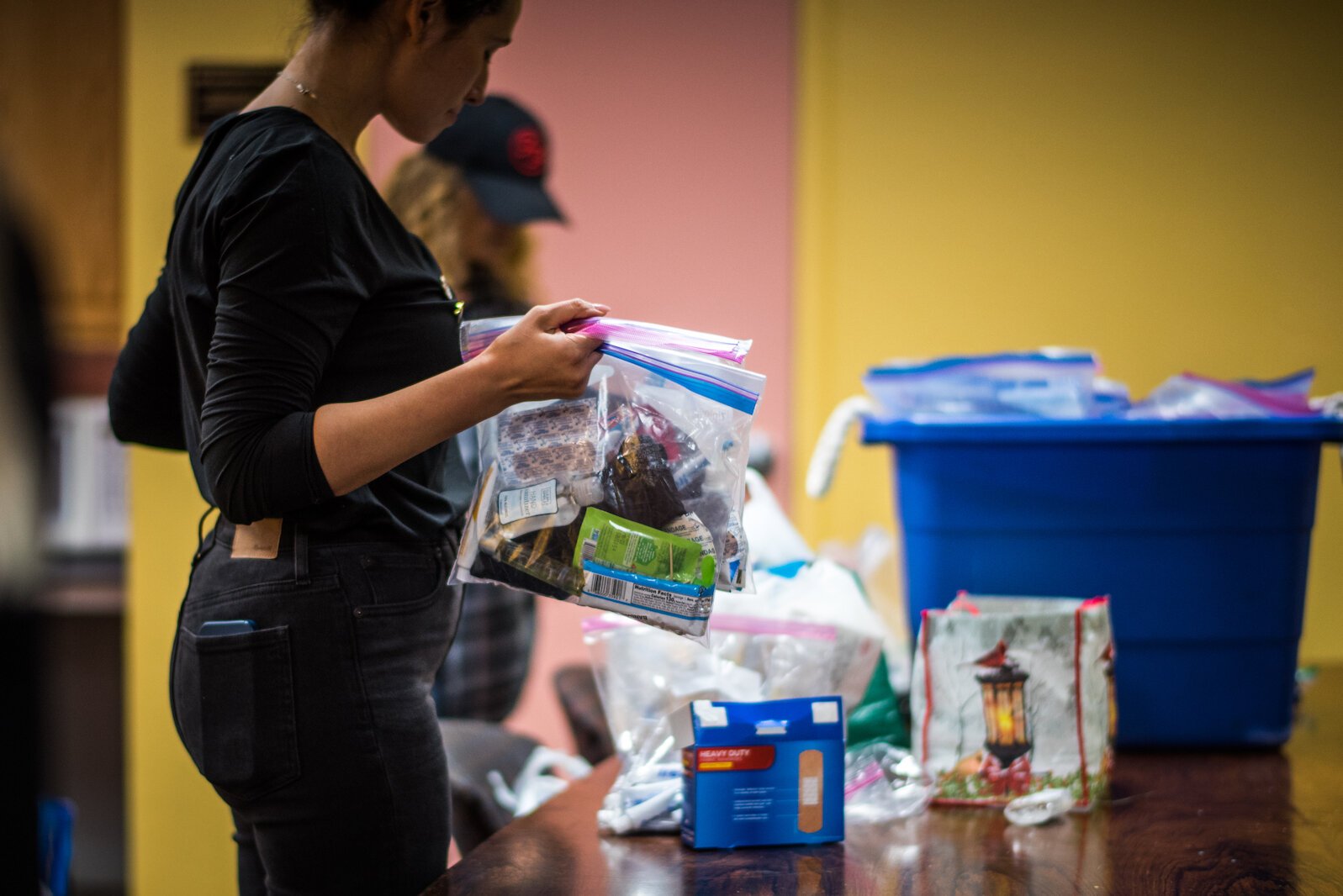

The needs of people living outside are many. U4U works to get them food, home-cooked meals, and “travel food” — something they could eat directly from the package. Plus they give out hygiene kits, clothes, supplies for pets, and on down to the most mundane of things, like phone chargers.

People living secure lives might panic if they lose their charger, and their battery icon is down to a sliver. Boone tells of people on the streets and in the woods who have to do guerrilla charging, plugging their phones into a business’s electrical outlets after dark.

As camps are broken up, the unsheltered try to find other, more-hidden spots to survive. U4U and other groups struggle to find the people who need help.

“Our folks have gotten very good at tucking in and trying to stay inconspicuous, and some groups are better at it than others,” Giambrone says.

“For us to get to them is very simple, but for us to not be obvious, complicates it. We can’t just pull to the side of the road, because someone’s calling the police or pulling over because they thought we’ve broken down.”

This leads to an invisible homeless population — out-of-sight, out-of-mind for many of Kalamazoo’s neighborhoods, Boone says. However, she says, “They’re in your neighborhood, now.”

Boone got involved when a camp appeared near her Eastside home. She was retired and wanted to make a “boots on the ground” difference without being swamped with the paperwork and case notes of her former career as a social worker.

Giambrone was a member of a cat rescue group when she saw that Kalamazoo’s unsheltered people also had animals that, in many instances, were the only loved ones they had.

He’s an engineer with degrees and experience. “It took 11 months of just resumes, resumes, resumes,” before he could get a new job. A family member provided financial help so they could keep their heads above water.

“This isn’t the first time in my life I’ve come very close to being homeless. I’ve always tried to give back where I could,” she says.

Giambrone says, “I’m surprised how more people don’t see it. I’m surprised it took me so long to see it. When you know where to look, you can’t avoid it.”

Working together

Giambrone pitched in to help dogs during the 2021 parvo outbreak at Kalamazoo’s camps. “I was trying to help where I could, there. I got to meet some of the folks who were getting displaced when the encampments were closed down.”

She cooked some big meals for some people living in tents. “I got to know the folks, got very invested, started making bigger meals.”

Soon, she became involved in other volunteer groups, networked, and U4U coalesced into a group of home cooks, animal lovers, and people of various skills looking to help.

There are many groups of Kalamazoo volunteers working to help people living on the streets and in camps. U4U has developed connections and can coordinate with this growing community of helpers, Giambrone says.

“The nice thing is, is that most of us all know that we couldn’t manage just the sheer magnitude of this as just one group. So, every group has a wheelhouse that they play to really well,” she says.

U4U has also been working with groups not usually in the business of helping unhoused people.

Recently, Global Ties Kalamazoo, which hosts people from abroad to make cultural and professional connections, asked around if visiting Romanian aid workers could help serve Kalamazoo’s homeless.

Global Ties contacted the Kalamazoo Coalition for the Unhoused, who forwarded them to U4U.

They “knew by virtue of what my group does,” Giambrone says. “We go to the camps, we’ve forged relationships with many of the unhoused where, like, I have about 80 phone numbers (of unhoused people) in my phone.”

U4U knew how to reach people, and they knew how to cook. They also have been working with the Edison Neighborhood Association, where U4U has helped stock the neighborhood food pantry.

That’s how U4U and Romanian aid workers ended up at the ENA’s kitchen and community room, making food and assembling survival kits, which they then passed out to people in need outside of the PFC on Oct. 25.

The Romanians have been busy back home helping war refugees from Ukraine, and were eager to do similar work in Kalamazoo, Giambrone says. “They seemed surprised that issues with homelessness that they encounter back home are so similar to what we have going on here.”

The international crew baked muffins and made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. It turned out that PB&J was an exotic dish to the Romanians — “They had no idea what it was!” Giambrone says.

“When they met our unhoused people, they were friendly and everyone really enjoyed meeting them as well,” she says.

Organizing in chaos

U4U’s work includes a lot of coordinating individuals with needs: “Okay, they need to see the doctor, these guys needed socks, these guys needed dog food,” Giambrone says. If their team can’t do something, they contact the doctors of Street Medicine Kalamazoo, Kalamazoo Mobile Closet for clothing, or other groups.

“Now, especially with the weather getting colder and all of the shuffling, it’s hard to reach a lot of our folks. Phones get stolen, phones get lost, charger chords are a hot commodity….. It’s a lot of grapevine, too. ‘Have you seen so-and-so?’ ‘Yes, they’re over there,'” she says.

“We inevitably find the person we’re after, but then we find more people.”

Boone describes a chaotic social environment among the unsheltered. “I don’t have rose-colored glasses,” she says, and she knows that many have issues like mental illness and substance abuse that hold them back. She suspects she’s been in “scary situations without realizing they’re scary situations (when) going tromping out here.”

But the face-to-face interactions do a lot of good with a population that has lost trust in much of society.

Giambrone says, “The big thing with us is, we’ve built the trust with our folks. They’ll tell us what their needs are. A lot of them just don’t trust agencies like — a lot of them have a problem with the Gospel Mission,” she says, pointing out that the Mission won’t allow pets and doesn’t have medical staff on site.

Boone says that “respect and dignity” is what United for the Unsheltered hopes to offer.

“I’m more like the mom, or the grandma, (who’d say) ‘now, are you sure you want to do this?'” Boone says with a laugh. But she also “recognizes they’re adults.”

Giambrone says, “One of the things they know about me is I’m Italian, so I’ll yell at you, and I’ll feed you, but both come from love.”