The Voices of Youth Kalamazoo program is a collaboration between Southwest Michigan Second Wave and KYD Network, funded by the Stryker Johnston Foundation.

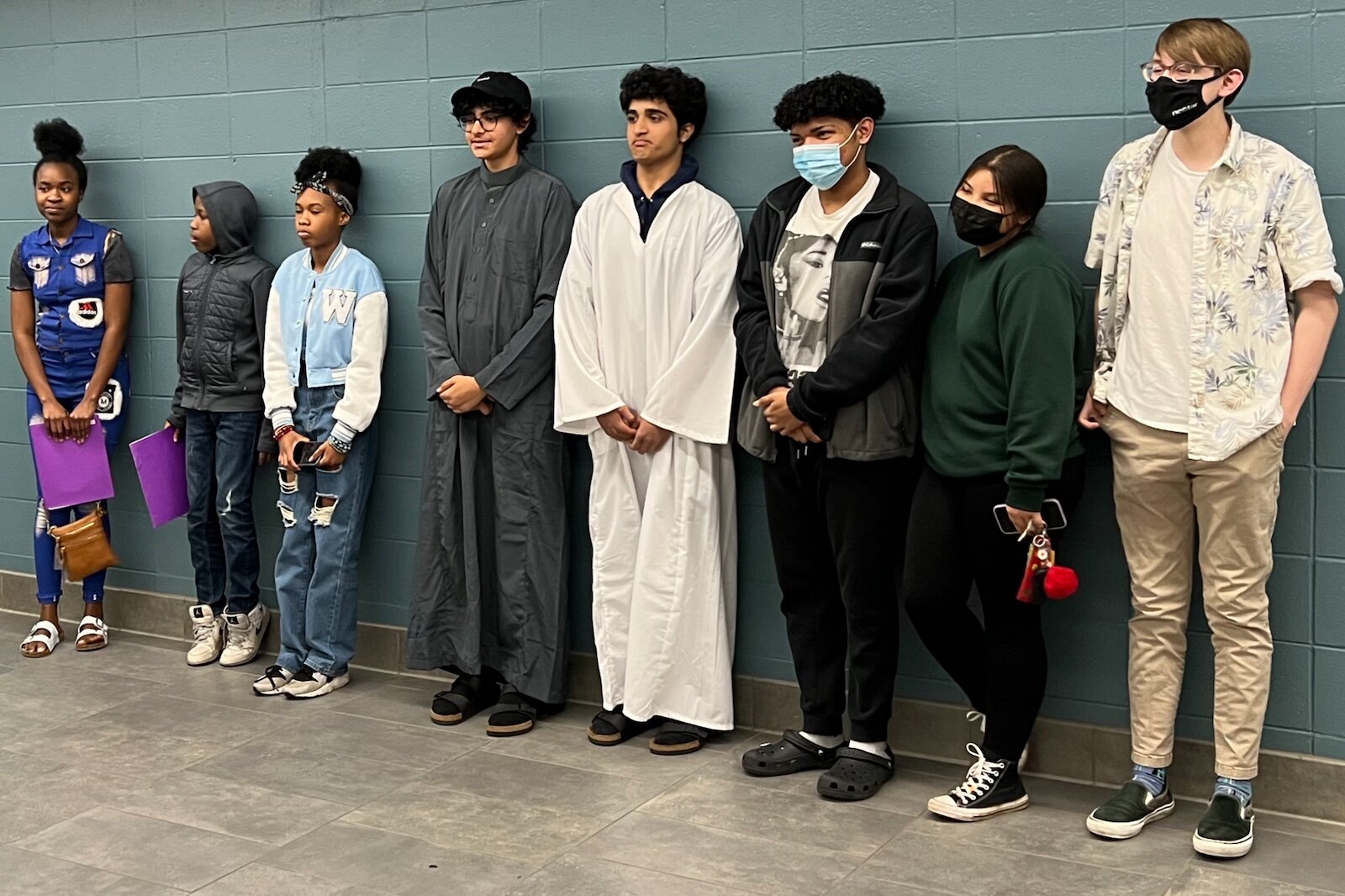

When the students showed up to that first Voices of Youth session at the Maple Street YMCA in early April, it was clear they were a little nervous. They looked around hesitantly at the mentors, the spread of food in the corner of the room, and at each other. Most students had taken classes together or passed one another in the hallway at school, but they came to know one other far better through this five-week-long training journey that included bonding exercises.

Voices of Youth is a program through Southwest Michigan Second Wave Media funded by the Stryker Johnston Foundation, in its second year. The first year’s sessions took place virtually – the youth and mentors communicating through Zoom and mid-week Google Meets for phone calls. The program centers around teaching local Kalamazoo teenagers how journalism can raise awareness around issues that are important to them.

This year’s topics were transportation, youth mental health, and policing.

This year, Second Wave partnered with KYD Network to really hone in on how to make the programming as effective as possible for the youth that chose to be involved. The mentors and program’s leadership attended a virtual training with KYD Network the month before the program started. As one of the mentors myself, I can say without that training, this year’s Voices of Youth program would not have been as fulfilling for the youth, or for me as a mentor.

How it began

I was able to sit down with Kathy Jennings, the program lead for Voices of Youth, and with Omarion Sanders-Fields, one of the older students in the program. Kathy and I discussed the differences and improvements made since year one of Voices of Youth. Sanders-Fields and I reflected on this year’s program, and how it affected his ideas on creating artwork, current events, and what he most enjoyed about the classes.

So, whose idea was Voices of Youth?

Jennings looked up for a moment, repeating the question to herself as she collected her thoughts. She says the leadership of Second Wave Media in Detroit talked to those who were worried “the youth in the community were losing their understanding of how civic government works and the role of journalism in that.” Their answer to that concern was the creation of Voices of Youth.

The original program was launched in Detroit right when the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020, so naturally, those stories turned into how youth were reacting to the lockdown. Soon after, the program launched in Kalamazoo in 2021.

“Voices of Youth is an extension of Second Wave’s mission to give voice to those not normally heard,” Jennings says.

Student projects

As an art mentor, I was relieved when I asked Sanders-Fields whether or not he felt his voice was heard in the program, and if he was able to control the direction his photography project took. He thought for a moment and answered simply, “yes.”

On the first day of the program, Sanders-Fields chose the topic of policing, not just in schools, but in the community as a whole. He was responsible for taking photos that represented the ideas we came up with as a group surrounding the problems in policing, and, most importantly, the solutions.

In its most simple form, the Voices of Youth art students described the problem in policing as a lack of education that leads to targeting minorities. Conversely, their position was that the solution is to educate the police about inherent bias, race, and mental health. Some of the students also spoke of how when police officers are armed, it is more intimidating than comforting.

These ideas were expressed with a white shoe stepping on a black shoe, to represent the problem. The solution is illustrated with photos of a “Black Education Matters” sign, a close-up of a hand writing a letter saying “Black Lives Matter. I wish to be treated equally like every non-person of color gets treated…” In the collage, Sanders-Fields attached flowers and bright colors around the photos coinciding with the solution, and a red and blue square of see-through plastic over a picture of a former Kalamazoo Public Safety officer who represented the police in the art piece.

Sanders-Fields says he joined Voices of Youth because he felt it was a good opportunity to meet more people and that the money sounded good. Each of the youth were paid $30 for each session they attended, and $150 for their final project. Sanders-Fields decided that the best way to portray his feelings on policing was to take photographs and then make a collage from those photos and other materials.

Although the Voices of Youth program focused on the tenets of journalism, one integral part of journalism is multimedia. The majority of the youth in this year’s program chose to be involved in the visual art portion. This created a heavy focus on photography and metaphor.

When I asked Jennings what was different about the second year of Voices of Youth, she says that meeting in person rather than via Zoom was a significant change. She also brought up the KYD Network training the Voices of Youth leadership and mentors have gone through and how important it is been to understand how to better provide quality youth programming.

“Because this is such a learning, growing process, there’s a very steep learning curve, we are learning how to be a youth-serving organization,” Jennings says.

Jennings also described one of the major differences between year one and year two as “the youth were demonstratively more engaged” as a result of meeting in person.

When I asked Sanders-Fields what his favorite part of the program was, he immediately says “putting the artwork together, and the little conferences because me, Leland, and Emily are tight like that.” The conferences he refers to were the meetings held between the journalism and art students, and all the mentors at the beginning of each session. The program lead and project editor Earlene McMichael facilitated these meetings and helped the youth understand the role of journalism in the community, the basics of how to craft an effective article, and how visual media can support an article.

It’s about learning

When local photographer and social media manager Fritz Klug presented on week four of the program, the youth were all very involved. They were talking over each other trying to show Klug how they hold their phones and telling him which settings they use most when taking selfies. Klug spoke of how he practices on his family and friends when it comes to his photography and encouraged the youth to do the same.

Later in that fourth session, Victor Ledbetter, director of training at the Law Enforcement Training Center at Kalamazoo Valley Community College, spoke during a mock press conference. The youth worked with the mentors to write questions for Ledbetter. Mahdi Hassnawi, a Voices of Youth student doing artwork for the mental health story, asked: “Do you think that there should be levels of weaponry, or other combat training, rather than officers being armed?” Ledbetter answered: “The uniform is a trigger. We need officers in schools to develop relationships. To be an officer in uniform, without being armed, is to be a target.” He added that officers “need to be armed in schools in case something popped off.”

What implicit bias is and how his police officer’s training academy seeks to combat it were other key points of Ledbetter’s remarks. “Show me a person without a problem; you show me a person who doesn’t exist,” says Ledbetter, quoting one of his mentors. Ledbetter lamented that there are 1,800 hours of training required to be certified for barbering and cosmetology in Michigan, and only 594 hours of training are needed to become a police officer. Program participant Mahdi Hassnawi found the figures revelatory. “You can shoot people with less training than to cut someone’s hair,” he said.

When Ledbetter asked if they learned anything from his presentation, the students all raised their hands in the affirmative.

That’s the main point, right? Learning.

Almost every solution for each of the three problem areas that the youth chose to focus centered on education. As the art mentor, it was clear to me on week one that the youth had many ideas on how to solve the problems of school transportation, policing, and mental health.

Firstly, they said students should not be held responsible for absences when their bus route was canceled or the driver called in sick. As it regards youth mental health, their experience is that adults do not listen enough, and access to affordable therapy is virtually nonexistent. Their vision is that school policing would improve if students were asked why the altercation happened, instead of punishing all involved equally.

And a common solution, according to the youth, to each and every topic was people listening to one another.

Voices of Youth lifts up the issues important to young folks in our community. It allows youth to express how they think the problems directly affecting them can be addressed. The next session starts in Battle Creek soon, and it will continue in Kalamazoo later this year in autumn.

The articles and corresponding visual media from the most recent program were displayed at Rose Gold Coffee Company, 220 W. Michigan Ave. in downtown Kalamazoo, during Kalamazoo’s June Art Hop (June 3).

Casey Grooten was the art mentor for the 2022 Voices of Youth Kalamazoo program that took place in April and May.