A conversation with Imams about the past, present, and future of building community

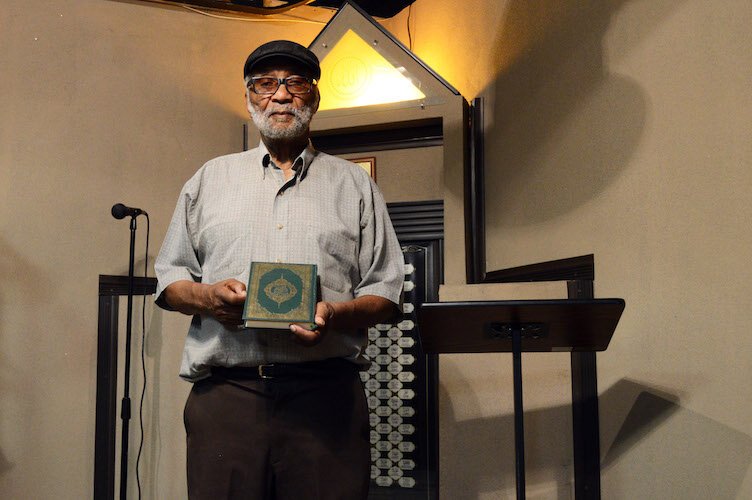

Imam Warithudeen Mohammed II has a message of love. He talked about that and more when he visited Kalamazoo recently.

We were waiting for Imam Warithudeen Mohammed II.

He was on his way from The Mosque Cares, his ministry in Hazel Crest, Il., south of Chicago, to visit the Bilal Islamic Center on East Main in Kalamazoo’s Eastside neighborhood, and then to speak at the Douglass Community Association, Aug. 10.

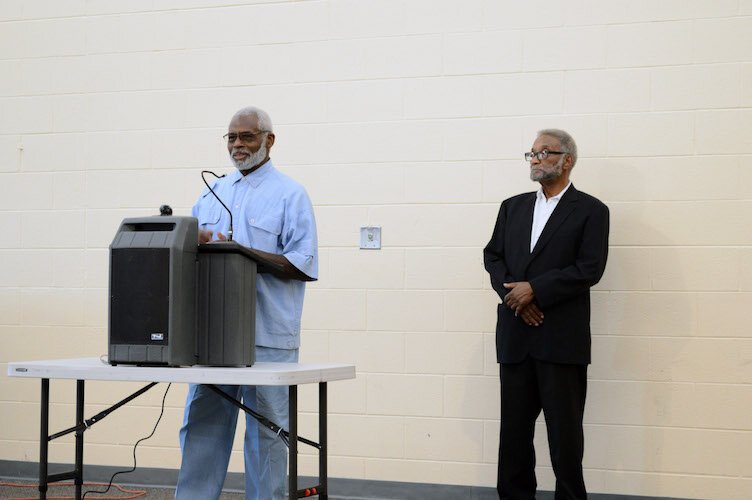

He did arrive, and later left to speak at the Douglass before a mixed crowd including Mayor Bobby Hopewell, Deacon Patric Hall of St. Mary Catholic Church, and about 40 others from Kalamazoo and as far away as Saginaw. Mohammed delivered a wide-ranging sermon centered on his family’s evolution as Muslims, and how Islam teaches that God created people as “tribes and nations so we would learn to love one another, and not despise each other. So we can benefit one another and learn from one another.”

But before the speech, the guest of honor was late to Bilal. Traffic out of Chicago on a Saturday afternoon can be a pain. So the brothers and Imams of Bilal talked of where the United States is now, and where their neighborhood of Eastside is now.

Bilal

For Second Wave’s On the Ground Eastside coverage, we met Hassan Mateen of The Lil’ Fish Dock. Not only does he make a fish sandwich that’s been called “the bomb,” but he’s also Imam Mateen, one of the founders of the Bilal Islamic Center, 1715 E. Main Street, across from his restaurant.

Mateen and his wife Laila Mateen began their mosque 50 years ago in the old Douglass Community Center. The mosque has been active in the Eastside since 1985, but didn’t have a permanent location until 1996. Bilal’s current spot opened in 2008. They were soon seen as a “positive presence” in Eastside, according to a 2010 Kalamazoo Gazette story.

Imam Mohammed is the biggest guest speaker the small mosque (20-30 members) has hosted. He is the 51-year-old son of the late Warith Deen Mohammed, and the grandson of Elijah Muhammad.

His grandfather founded the Nation of Islam in 1930s Detroit. Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, and Louis Farrakhan came out of the Nation. The organization encouraged black enterprise and independence; it also encouraged separatism and taught that whites were of the Devil.

Muhammad’s son Warith Deen saw that a lot of the Nation’s teachings contradicted the Koran. Mateen says that the son spent most of his life “bringing us away from his father’s teachings, because his father’s teachings was not Islam.” However, Elijah Muhammad did serve to “clean us up, get us ready for the real Islam,” he adds.

Under the original Nation of Islam, “We were one of the most racist people on the planet Earth because of Elijah Muhammad’s teachings. He used to tell us — now, I don’t mean any harm — but he said that the white man is the Devil, and the black man is God. And that’s totally wrong,” Mateen says.

“We were not practicing Islam when we was following Elijah Muhammad, because he did not teach Islam. It was sort of a black supremacy thing, you know. He (Warith Deen Mohammed) led us away from that, to the real Islam.”

Though controversial, the original NOI was non-violent, Mateen points out. Elijah Muhammad ended every speech with, “Do not do unto no one that you wouldn’t have done unto thee,” Mateen says. “He didn’t teach us to run out into the street and start a war or riot.”

In 1975, Muhammed died, and his son disbanded the Nation of Islam, eventually forming the American Society of Muslims and The Mosque Cares. Farrakhan then took up the NOL name for his own controversial organization.

Now with the grandson taking the head, “we’re going to get back everything we lost when we came into this country,” Mateen says. “I believe that Warithudeen Muhammed II is the one who will lead us to that height. He’s a businessman, not like his father.”

Mateen has felt racism aimed at him coming from whites and has seen whites called “poor white trash” by other whites. “Everybody’s not like that, don’t get me wrong. But I don’t see how anyone could hate someone because of the color of their skin. That don’t make no sense. The person didn’t create himself. God created him, created everybody. And he created everybody on an equal basis, everybody alike,” he says.

“A child, I don’t care what race he comes from, he cries the same, he doesn’t cry in Japanese, he cries like any other child, ‘Whaah!'”

We cry the same, “and we die the same,” Mateen says.

45

In the time between Second Wave beginning this story on Bilal and Mohammed’s visit, national events have inflamed the subjects of racism, religious bigotry, xenophobia and open white supremacist terrorism. President Trump’s tweets attacked four congresswomen of color, some Muslim, tweeting that they originally came from other countries, and that they should “go back….” Only one, Rep.Illhan Omar, D-Minn., is an immigrant, a Muslim from Somalia. Trump later triggered chants at a rally of “send her back” when he spoke about Omar.

Then a white gunman massacred 22 people at an El Paso Walmart. He later confessed he was shooting to kill Mexicans and beforehand wrote a screed on a supposed “Hispanic invasion,” reflecting the language used by the president and Fox News about the latest waves of hopeful migrants.

The subject of Trump’s words spurs Bilal Imam Hamim Rasool to say, “As far as sending Omar back — everybody in this country is an immigrant. Why don’t he talk about sending his wife back? She’s an immigrant. He’s just picking on those women because, Number One, they’re women and, Number Two, they’re women of so-called color. And for a president in 2019 to be talking like that, it’s ridiculous. We should be focusing on the human rights in this country and all over the world. And the breakdown in terms of human rights in America, the breakdown for young people having the so-called American dream — that went out the window, there’s no such thing as that any more, if it ever did exist,” Rasool says.

He adds, “I’m a Vietnam veteran, combat-wounded, two purple hearts, three bronze stars, and when I got back I had to fight for certain rights in this country. It shouldn’t be. I’m more patriotic than 45 is. He never fought in any war. It’s ridiculous to talk about sending anybody back, when everybody in this country are immigrants.”

Rasool points out that “Imam Hassan Mateen, from the time I’ve known him, has been very aggressive in terms of community outreach.” His is work to “make America beautiful, for real, for all people.”

Community equals “Come Unity”

Yusof Al Kahui, “also known as Archie Davis,” he says, patiently requests permission to speak. He says that Islam taught him patience and respect.

“I was incarcerated for 35 years.” In prison he studied literature from The Mosque Cares. “It encouraged me a lot to do the right thing. To follow that which is right and to do good.”

When he got out, “this community actually embraced me, helped me understand the importance of family and of community. I help around the community, I do neighborhood watch. I walk around just to make sure everything is right. I help sisters cut grass.and be productive.

“Also, I just got a new job… And for the first time I’m also sharing with the community, that I got a grant to open up my own restaurant. This is one of the things that Waruthdeen Mohammed is teaching us, to be productive, to take care of your business as a man. You have responsibilities — take care of your community, and take care of your family.”

African Americans establishing their own business is part of the “New Africa” concept, Imam Robert Saleem says. Along with Bilal’s building, they own the four-unit apartment building next door and a nearby single-family house.

“Though we’re establishing a New Africa, our first tenant was Caucasian,” he says with a laugh. They have a mix of current tenants. “We’re not trying to be, you know, color-struck as far as development goes. It’s the concept of being a light in your neighborhood.”

Some of their renters are able to pay months in advance, some are struggling. In some cases they’ve given homes to people who’d otherwise be homeless. The mosque is not in business to make money, Saleem says. “Nobody’s paying market rent, I’ll put it that way.”

Before Bilal opened on the block, the buildings were vacant and teeming with crime. “We got resistance when we first came in, because this was a haven for drug deals,” Saleem says.

Cars would drive by, threatening stares emanating from the windows. New construction at the buildings would be ruined overnight. The Mateens had a bullet fired through their house and the windows of a parked vehicle were shot out.

Saleem says that one way he worked to combat crime was to hire from the crowd that always seemed to be hanging out on the street. He had one working on the property. “When I told him, ‘Okay, you did a good job. Prophet Mohammed said that “you should pay a person before his sweat dries.”‘ He liked that!”

Mateen remembers when “a one-armed guy, he came in and stole a TV. With one arm!” Everyone laughs.

“There use to be a crowd out there in front of the Fish Dock. Almost 24 hours a day. Now, they’re gone,” Mateen says.

Isolated from the rest of Kalamazoo by the Kalamazoo River, the through-traffic corridors of Gull Road and East Michigan Avenue, and cut in two by East Main Street, Eastside has seen its times of struggle. What could bring it back to life?

“There is life in the Eastside. There is life in Kalamazoo, period,” Max Jaber says.

Jaber, a Palestinian immigrant, ran the Shop-N-Save next door for a long time. He recently closed due to family issues, but while spending time behind the cash register for nearly two decades he figured out how to deal with trouble-making kids in his store.

“You just have to be their friend,” Jaber says.”And that’s how I took it. I respect every single kid that’s out there, they have respect for me.”

“Everybody in this neighborhood knows this man, everybody!” Saleem says.

“We had a hard time,” Jaber continues. “But we had respect for all them kids, they had respect for us. I may kick them out for a while, but that’s it. There’s no reason for me to call the law on them, if you do something wrong.”

He would tell the kids that, “‘outside of the store, the law and everybody knows what you’re doing. So I’m going to be your friend.’ I would tell them, ‘this is not good, don’t do that.’ Thank God there’s a lot of kids that’d listen, a lot. I see a lot of kids, they have their own stores, their own jobs, stuff like that.”

He recently met a couple he’d known when they were teens, who now have their own salon. “They said ‘thank you for everything.’ I said, ‘For what?’ ‘For everything you did.'”

In Eastside, “now, it’s real good, it is. We just need help from the city! That’s it. I think for 20 years we’ve never had any kind of help,” Jaber says.

He continues, “Before Hassan, you couldn’t even go outside. But you could go outside right now, talk to anyone you want. Not one person’s going to say anything bad.”

Imam Les Malone remembers Mateen saying that the word “community” was really two: “come unity.”

Malone says, “When you do good by people, it sticks with them.”

He then quotes a song he remembers, “How does it go? ‘What the world needs now is love, sweet love?’ A lot of people look at the fact that charity only comes in the form of cash. But sometimes just a smile and a good word to a person can go further than a dollar bill.”

“And a dollar bill don’t go far!” someone says.

Surviving 45

So, instead of calling the police, try to help those who are doing bad in the neighborhood?

“That’s what I would do. Respect them, go along with them, try and help them,” Jabar says. “There’s a lot of people out there that do want to be helped. They’re not going to come and tell you.”

Bilal is trying to build a Muslim community on their block, he says, “Not just for Muslims only. The name ‘New Africa’ — I hope it exists one day in this community, I hope. But it’s not just for Muslims. Anybody can come over here (to the Bilal properties), anybody,” he says. “I’m a Muslim, but I’m not from here. I’m from Palestine.” Jabar has been working alongside of the Imams of Bilal, though he just became a praying Muslim a couple years ago.

Rasool says, “I think we will survive 45, I think we will survive followers of 45. Islam teaches us to overcome, to endure, to replace that which is bad with good, no matter what. Take your personal feelings out, to do good.”

The Koran also commands Muslims to “be industrious,” Rasool says. “Before, the community was in shambles, now look. Grass is being cut on the lawns, there’s nobody hanging out. A lot of us brothers, we volunteer, we go around at night, make sure the women and children are safe. We check on one another, and if somebody has a problem, we’re there to help resolve it.”

Arrival

Then Imam Warithudeen Mohammed II and his entourage arrive. After a round of the traditional greeting As-Salaam-Alaykum, we get a chance to ask him a question before he has to rush off to the Douglass center.

What can a mosque like Bilal do to help their community?

He turns to the people in the room. “Can I ask, do you all feel like you’ve made a difference?”

“Yes sir, we do,” Mateen says.

“I can only go from my own experience,” Mohammed says. “By no means do I separate myself from just average black African American person who identifies with the culture of America… You don’t see yourself separate from the people, but if you’re Muslim, people see you.”

The black Muslim movement “represented an evolution not just in mindset, but in overall appearance of what people thought African Americans were and looked like. Clean, respectful and intelligent. And African Americans in pop culture, in popular society, weren’t known for those aspects.”

Poor communities need to be lifted up — Mohammed says he recently heard an interview with a sociologist on the subject. “The only solution he saw was economic. And more freedom to live your life as an individual, to be able to own a home… to pay your bills and live a family life.”

And with that, he had to rush off to his appearance at the Douglass.