Answering the cry: A Kalamazoo rehabilitator’s journey of love, loss, and saving wildlife

“We need to start thinking of wildlife, particularly urban wildlife, as native, indigenous to the land that we developed. As such, we need to learn how to coexist in a way that we don’t feel like they’re encroaching on us, but rather that we’re encroaching on their habitat."

KALAMAZOO, MI — One word describes a typical wildlife rehabilitator in Michigan: dedicated.

The work can be grueling with extraordinarily long hours and no salary. Wildlife rehabilitators are licensed by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The DNR provides the training, license, instruction, and many rules. But there is no organization that pays for performing the service. For many called to this work, it’s a labor of love.

A midnight craving turns into a calling

Celine Saillant (pronounced sih-LEEN SA-yawn) of Kalamazoo has been licensed as a Wildlife Rehabilitator for four years, but her concern for the well-being of wild animals goes back a long way.

She says that about 23 years ago, “I had a hankering for ice cream at midnight. I went downstairs and I heard this crying and I thought, ‘What is that?’, and I went outside and there were two baby raccoons in my yard and they were screaming their heads off. Dogs had killed the mother, and I was just so distressed I didn’t know what to do.”

She made several phone calls and finally reached a raccoon rehabilitator.

“When she picked up the phone, all I heard was this noise that I now know is crying baby raccoons. She must have had 50 of them.”

The woman then instructed her on how to raise the babies. “That was the beginning. Throughout the years, I was just kinda the go-to for people. Any time somebody had a question about wildlife, they always asked me. But I didn’t know how to go through the proper channels to get licensed, and that was difficult.”

For the love of raccoons

Recently, Saillant had as many as 35 animals, most of them very young raccoons, in her well-equipped facility in her home in Kalamazoo’s Winchell neighborhood. With most of them requiring syringe or bottle feeding every three or four hours and constant cleaning and sanitizing, Saillant says her workday often goes from 10 a.m. to 2 a.m.

“

Celine Saillant vaccinates a raccoon.

I am limited in what I can do. There are only 24 hours in a day; I wish there were more. I run out of space, I run out of daylight, I run out of energy. So I can only take so many animals before I have to say no, and that’s hard.”

In addition to the constant feeding, cleaning, medicating, and showering of affection, there’s an occasional rescue of an animal that requires round-the-clock care.

And inevitably, there are tearful times, such as recently when Saillant checked on a very sick baby raccoon in an incubator and lifted a lifeless little body.

She says young raccoons are the most difficult animals to care for, and she and one other person are the only rehabilitators in Kalamazoo County qualified to do that.

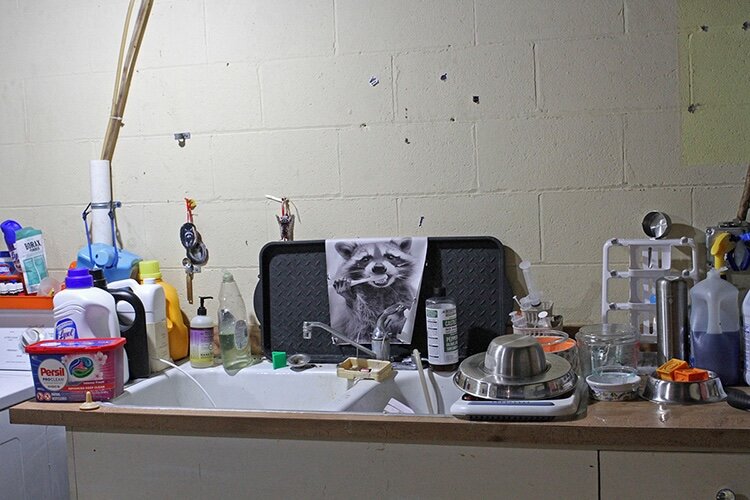

Saillant has two volunteers who help with laundry and cleaning the facility. “They can’t handle the wildlife,” she says, “but they do things that are very important, like the cleaning that facilitates a hygienic environment for the animals to be in.

“I do about three loads of laundry a day. We go through a lot of towels and blankets and sheets, and hammocks. I use disinfectant and bleach; we’re very careful with that.”

All the items needed for rehabilitation work fill many shelves.

Saillant gets some donations to help obtain such things as bandages, intravenous and subcutaneous fluids, vaccines, other medical items, general supplies, lots of food, and toys for rambunctious young animals to play with.

“People will drop off supplies,” she says. “I’ve had paramedics donate things. I’ve had doctors’ offices donate syringes, for example.

Trained to care for rabies vector species

“In Kalamazoo, I am the only person who does rabies vector species,” Saillant says. “There are different wildlife rehabilitators for different species. For example, there’re people who work with fawns and that’s it. There are a lot more wildlife rehabilitators who work with squirrels and possums and things like that. There aren’t too many people who are willing to work with the species that I’m willing to work with. And the licensing is different.”

Celine Saillant moves two raccoons prior to cleaning their cage.

Although Saillant is licensed to treat rabid animals, she has never done so.

“Raccoons are some of the species that are tested quite often, probably more often than most species, and we haven’t had a positive raccoon rabies in Michigan in several decades.”

Other animals that can get rabies include bats, skunks, squirrels, cats, and dogs. Bats cause the most concern, but Saillant says, “There have been a few positive cases recently, but that said, it’s still very, very rare. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t always practice caution; you should always have a healthy fear of any disease, particularly rabies. Always wear gloves, always use a towel, practice good hygiene.”

Spring and summer are especially stressful for rehabilitators because that is when nursing animals are killed or relocated, and their babies become helpless orphans.

A young fox is picked up for rehabilitation. Its mother was killed by a man protecting chickens.

Not long ago, Saillant dealt with one of her worst cases. “A woman had relocated a nursing raccoon mom; she hired a wildlife-removal company,” Saillant says. “Three babies were left behind in a tree. Because they were looking for mom, they had fallen from that very tall tree, and they sustained injuries. One baby had a cracked jaw from its teeth all the way to the back; the upper jaw was completely shattered. I had to feed that baby with a syringe every two hours; it was painstakingly difficult. But what was really horrific, just ghastly, was that they were covered in flies. The flies were literally just eating them alive.”

One baby died, but two are recovering well. Raccoon babies stay with their mother for about a year. Orphaned ones must be bottle-fed every four hours for a few months.

From rehabbing to re-wilding

Saillant cares for more than 110 animals annually. The most common ones are raccoons, squirrels, and possums. Recently, in addition to the many raccoons, she treated two groundhogs and two rabbits. A rehabilitator’s goal is simple: to make an animal fit to return to its natural way of living.

Two baby fox squirrels were found orphaned on the campus of Western Michigan University.

Saillant attended Western Michigan University and received a bachelor’s degree in psychology based on behaviorism. (One definition of behaviorism is “it suggests that all behaviors are learned through interactions with the environment, primarily through conditioning, which involves reinforcement and punishment.”)

“I use behaviorism just about every day in my line of work,” she says. “When you have many animals in a confined space, you need to be able to figure out contingency plans that tie into feeding safely, vaccinating, medicating, treatment, positive reinforcement — all those things tie into animal rehabilitation. It also relates to educating the public in a way that’s not abrasive or contentious — my being a resource and being open to dialogue with the public.”

The hidden dangers of trapping

What’s to be done with a nuisance animal where you live? Saillant says live-trapping an animal and relocating it doesn’t work. Recently, she corrected a man who thought he was being humane by trapping groundhogs on his property and releasing them into the country near a good source of water.

This rat trap seriously injured the paw of a raccoon.

“It’s terrible on them. They die from that,” she says. “Let’s say I picked you up and I plopped you in the Amazon, and you had no currency, you couldn’t speak the language, you couldn’t watch out for predators because you didn’t know where to go, and there was competition for food. How do you think you’d do? You would starve to death.”

She also notes that the Michigan Department of Natural Resources prohibits relocation because it can spread diseases.

The problems of development

“Development is turning into a huge problem for wildlife,” Saillant comments, referring to housing subdivisions, shopping centers, golf courses, and any construction that makes land no longer natural. “When there’s competition for resources, for food, it creates what’s called a rebound effect. You have higher birth rates. The animals are deemed a nuisance, and we often do not contemplate why it’s happening. It’s just becoming a situation where the wildlife doesn’t have anywhere to go. That results in higher birth rates, more disease.

Celine Saillant holds a baby rabbit.

“When someone has a home that’s been inhabited by an animal like a squirrel, groundhog, or raccoon, we can easily do a humane eviction, and it’s not that hard, and it’s cheap. Let’s say, for example, you have a family of raccoons in your attic. If you make it uncomfortable for them, they will leave. Give mom time to move her babies and let her move them on her own. Or if you do trap, at the very least, just put them outside rather than moving them to some unknown place where you think it would be more appropriate for them to be.”

Saillant notes that a simple way to keep animals out of a dwelling is to keep it in good repair. Many animals view almost any opening as an invitation to move in.

Saillant wants to reduce the need for wildlife rehabilitators by educating the public.

“

A whimsical poster decorates the cleaning area.

My goal is to have fewer animals that need help, and do this by disseminating education to the public about how to manage wildlife. The majority of the cases we get are caused by human behavior. So, educating the public on how to coexist with wildlife in a way that indigenous wildlife can live in their own habitat without being displaced is important. That would definitely help. A lot of this is needless, really. It could have been prevented with some education.”

She continues, “I’m up late at night, and so I watch what’s going on, and it’s a whole new world. We have a feral cat population that’s growing exponentially; it’s out of control. That not only affects the birds, it also affects how native animals compete for resources with invasive animals that we brought here. The raccoons and the possums, not the cats, are supposed to be eating mice.”

Aiming to educate

Returning to her desire to emphasize education about wildlife, she says, “I would like to go into the schools and talk to students, and I want to build a website to educate people on trapping animals and why trapping — even when you’re releasing in a place where you consider it to be safe — is really the worst thing to do. Once you relocate an animal, for myriad reasons, it’s bad for the animal, it’s bad for the environment, and it creates a vacuum effect — you’ll just be doing it again because more animals will come.

A young raccoon anticipates getting fed.

“We’ve been so consumed with this idea that animals don’t belong in the city when, in fact, urban wildlife does exist and they’re right where they’re supposed to be. I think people are starting to realize that development is contributing to this. I prefer to respect indigenous wildlife as the beings that were here before us. They don’t understand property lines.

“We need to start thinking of wildlife, particularly urban wildlife, as native, indigenous to the land that we developed. As such, we need to learn how to coexist in a way that we don’t feel like they’re encroaching on us, but rather that we’re encroaching on their habitat.”