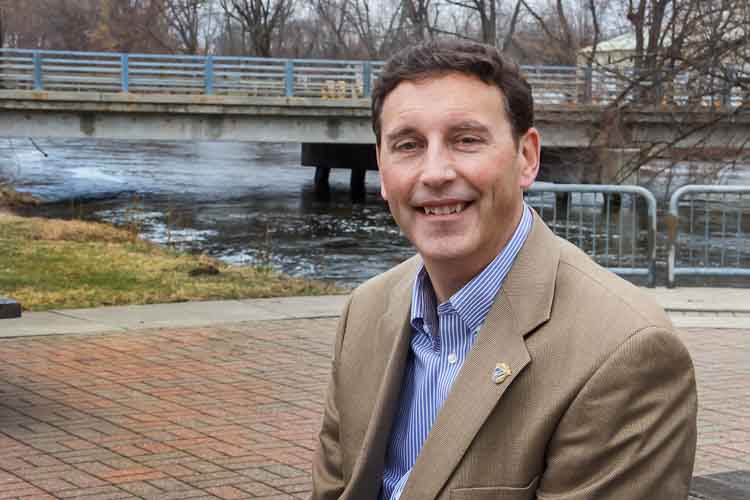

Waiting on a dam (removal): Otsego city manager Thad Beard on restoring the Kalamazoo River

Thad Beard wants to see development, fishing and recreation along the Kalamazoo River in the City of Otsego. But before that can happen, an old dam must be removed and some legacy contaminated sediments cleaned up.

The Kalamazoo River has been a part of his life since he was in the cradle.

He remembers golfing at a par three golf course along Kings Highway, which had one fairway along the river. He and his golf partners regularly avoided the hole since it had such a bad odor to it.

Meet Thad Beard, city manager of the City of Otsego, Michigan.

Beard was appointed to the position in January, 2000. Soon after he was hired in, the City of Otsego was formally identified by the state as the owner of the Menasha dam in the Kalamazoo River, which runs through Otsego. The dam was built in the late 1800s. Decades ago, Menasha, the company which operated a paper mill, used the dam for cooling purposes. The dam later became a collecting agent for contaminated sediments from upstream paper mill activity.

Because of large amounts of contaminated sediments lodged at the dam, this part of the river became part of a Superfund cleanup effort under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and was identified as having the beneficial use impairments (BUI)s of loss of fish and wildlife habitat and degradation of fish and wildlife populations as part of the EPA’s Area of Concern Program. The river also has six other BUIs under the program.

Beard is a local native who cares deeply about the Kalamazoo River. He graduated from Kalamazoo Loy Norrix High School in 1985, went on to get his bachelor’s degree from Great Lakes Christian College in Lansing, and earned his master’s degree from Western Michigan University in 1996. He entered the workforce with the City of Wayland for three years before landing with the City of Otsego.

“The Kalamazoo River has been part of my job at different levels since day one,” Beard says. “Around 1985, then-Governor John Engler provided an act that allowed paper mills that no longer had usage for dams to abandon interest in them. Menasha did so. Since the City of Otsego was one of the principals in establishing it, through a process of elimination, we were the last party remaining that had any ownership in the dam.”

Hence, the city was given responsibility for the dam, repairs to it, and inspection of it. As soon as the city was identified as the last remaining owner, it was informed that the dam needed some essential repairs.

“As a city, we didn’t have revenue to provide any type of a funding mechanism to repair or maintain the dam,” says Beard. “Thankfully, the PRPs (potentially responsible parties) stepped up and assisted us in the immediate repairs that were required.” Potentially responsible parties are those that are potentially liable for payment of Superfund cleanup costs.

It wasn’t until 2004 that the city finally completed work to encapsulate the embankments of the dam and remove all of its apparatus. The only remains are concrete pillars protruding from the water and the concrete basin that is the base of the dam. There is no mechanism in place to withhold the water at the head of it.

“We want the dam gone,” said Beard. “It’s a constant source of liability, and it’s considered a high hazard dam because of the contaminated sediments. We’re actively pursuing to have it removed.”

Another reason that the City of Otsego wants the dam removed is because property abutting the dam lies within their Downtown Development Authority (DDA) district. The DDA has plans for a redevelopment of the property along the river. However, none of that can occur until the contaminated sediments are remediated and the dam is removed. And because the dam is on a Superfund site, the city can’t touch it until the EPA and the State of Michigan grant them the authority to do so, Beard says.

“It all comes down to EPA forcing the responsible parties to complete the remediation,” says Beard.

In 2013, the City of Otsego received a grant through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative to complete a feasibility study on how to remove the dam. The $360,000 grant allowed the city to hire a consulting firm to conduct the study and come up with cost estimates.

“It’s now sitting on my shelf waiting to be enacted,” says Beard. “The State of Michigan is on board with us, the community wants the dam removed, and the DDA wants the dam removed.”

Estimated costs to remove the dam and remediate the contaminated sediments from behind the dam range into the tens of millions. The plan also calls for armored embankments to control the flow of the river and allow for more recreational use.

“We want to see that area become an attraction and a destination point for our downtown,” Beard says. “We’ve been successful in putting trails along the river, and we want to make it’s an area where people can go fishing and put canoes in.”

The DDA’s plans call for a fish livery, an amphitheater, a banquet facility, and condominiums along the river. It’s a multi-million dollar project that includes new roads and utilities as well.

“All of that is tied into the dam being removed,” Beard says. “I’m encouraged by the fact that there seems to be a more awareness recently of the need to get this done. It looks like we’re all on the same page in the direction of removing the BUIs and transforming the river, as much as we can, back to a natural state and a recreational river.”

It’s Beard’s goal to see that all this happens before he retires one day. Or sooner.

?This series about restoration in Michigan’s Areas of Concern is made possible through support from the Michigan Office of Great Lakes through Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.