Editor’s note: This story is part of Southwest Michigan Second Wave’s On the Ground Calhoun County series.

When one member of an Indigenous community goes missing or is murdered, the impact of these losses is felt by Tribal members throughout the United States, says Robyn Elkins, Tribal Council Vice-Chairperson for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (NHBP) in Calhoun County.

On Monday, she joined with other NHBP members and members of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi and the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi, who hosted their fourth March for Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) through downtown Grand Rapids in observance of National MMIP Awareness Day, which falls on May 5.

“We’re all related, we’re all connected,” Elkins says. “If we have a relative from another Tribe murdered or missing, we all tend to have personal connections, and it hits our community. It’s not an ‘our tribe or their tribe’ mentality; we’re all relatives. We need to make the general public understand the impact the loss of these lives has in our community.”

These marches, however, are also a call for accountability and the need to focus on unsolved crimes against members of Indigenous communities.

At the beginning of Fiscal Year 2025, the FBI’s (Federal Bureau of Investigation) Indian Country program had approximately 4,300 open investigations, including over 900 death investigations, 1,000 child abuse investigations, and more than 500 domestic violence and adult sexual abuse investigations, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

The local MMIP March was among numerous marches held throughout the country to raise awareness about the inordinately high number of unsolved cases involving Indigenous people who have been murdered or are missing.

Some may wonder why National MMIP Awareness Day is held on the same day as annual Cinco De Mayo celebrations, which commemorate Mexico’s 1862 victory over the French at the Battle of Puebla.

“Among Native Americans, May 5 was not randomly chosen to bring awareness to MMIP,” says Levi “Calm Before the Storm” Rickert (Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation), who is the founder, publisher, and editor of Native News Online.

The date was selected following the introduction of a resolution in 2017 by Montana Senators Steve Daines and Jon Tester recognizing May 5, Hanna Harris’ birthday, as a National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls, according to a post on the National League of Cities (NLC) website. In 2021, President Biden issued a proclamation designating May 5th as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) Awareness Day.

Harris was 21 years old at the time of her death, which occurred after she left the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation to go into nearby Lame Deer, Montana, to watch the Independence Day fireworks and never returned home. When her immediate family reported her missing, local law enforcement downplayed her disappearance. Four days later, a volunteer search team found her badly decomposed body in the summer heat of the Great Plains. Her body was so decomposed that forensic technicians could not ascertain whether she had been sexually assaulted or the cause of death.

Testimony from those responsible for her death confirmed Harris was raped and bludgeoned to death.

The downplaying by local law enforcement of her disappearance and death is part of a heartbreaking and discriminatory pattern that has plagued Tribes in the United States for decades, Elkins says.

“A lot of times these crimes go completely unaddressed,” she says.

Events following the murder of a young woman who was a member of a Native community in Alaska are among many unsolved crimes involving Indigenous people that validate Elkins’ claim.

Data from the U.S. Department of Justice indicates that Native women face murder rates more than ten times that of the national average. Fifty-five percent of Native women have experienced domestic violence (these numbers are low, as many cases are not reported or go unrecorded), according to a press release from the NHBP.

Elkins says the NHBP is among Tribes in the United States that have staff serving as Domestic Violence Victim Advocates. They work with victims and families to address immediate needs like safe shelter, food, and clothing, and the courts to advocate for victims.

Jurisdictional issues often impact cases

“As many people may or may not know, domestic violence is often done by a significant other and can lead quite often to being murdered or coming up missing,” Elkins says, as was the case with the young Alaskan woman.

“She was either married to or dating a non-Native person who ended up killing her. Her body was out in the snow. The local Tribe did not have jurisdiction over the area where she was murdered, so her family was told that they couldn’t move or touch her body because it could jeopardize the case,” Elkins says. “It was almost like they were building a case against us, not the perpetrator.”

For several days in frigid temperatures, family members stood watch around the clock over the young woman’s body until local law enforcement showed up.

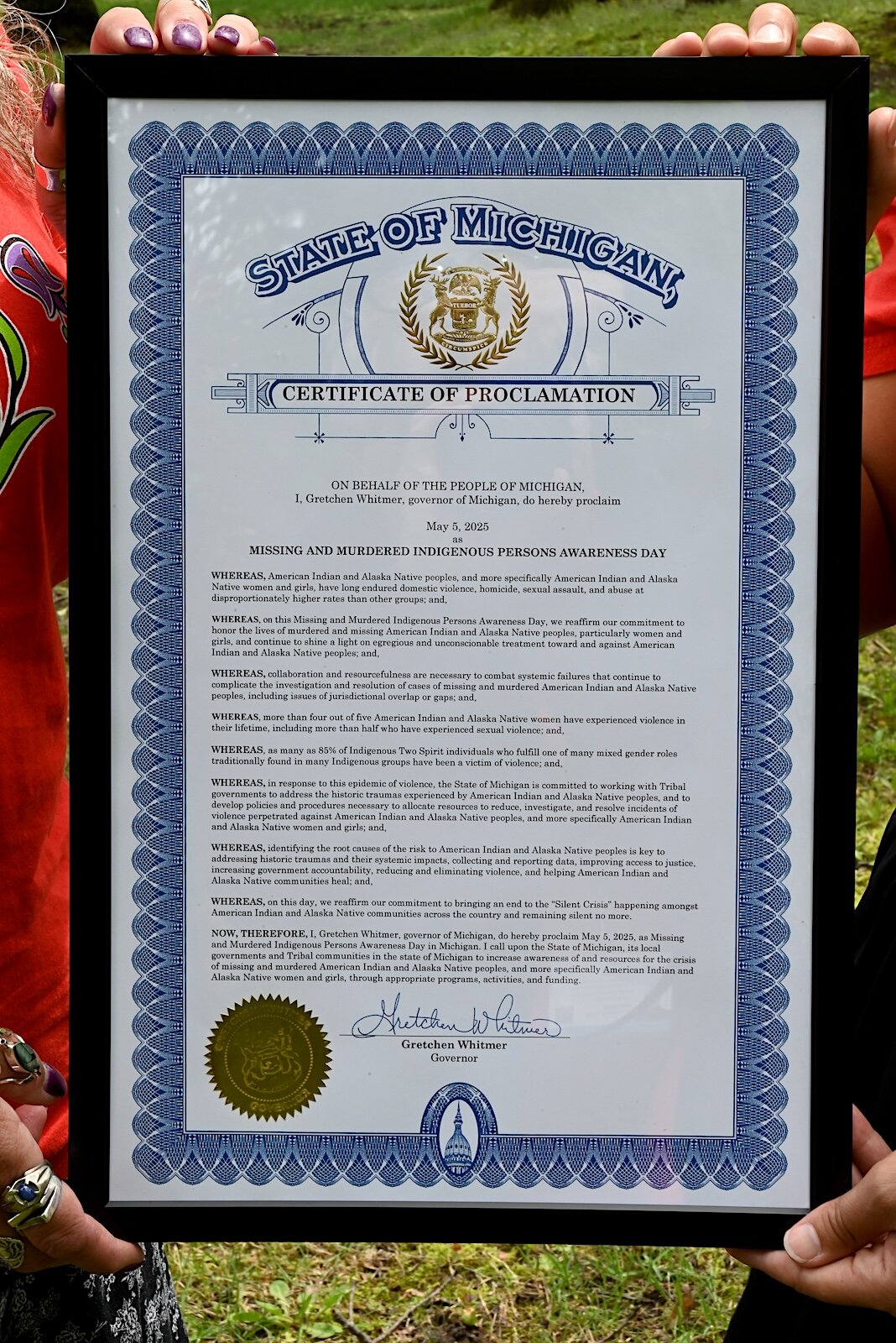

Proclamation from Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer declaring May 5, 2025 as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day.

“In the meantime, they watched this person who took their daughter’s life working around their community, trying to groom the next girlfriend or wife, and there was nothing they could do about it,” Elkins says.

These jurisdictional issues have long been common knowledge among non-Native individuals who know they will face little or no repercussions for crimes they commit on Tribal-owned lands.

Elkins says this has been exploited since Colonialism, when Native Americans were forced to live on reservations located in remote areas after plans to eradicate them failed. The earliest remotely-located reservations often abutted work camps populated by white men who were building railroads, mining, or logging.

“Our people were often sitting ducks, and law enforcement saw us as a thorn in their side,” Elkins says.

Justice denied or delayed

The NHBP has its own Tribal Police Department and Tribal Court because it has the financial resources. Elkins says the Tribe, which has Sovereign Nation status, has working relationships with law enforcement in neighboring communities.

Those Tribes that can’t afford to pay for their own Tribal Police and Tribal Court have no choice but to work with neighboring law enforcement.

The NHBP is one of 574 federally recognized American Indian tribes and Alaska Native Villages in the United States. The ability of these Tribes to mete out justice is limited to their own geographic boundaries. At some point, when all other avenues are exhausted, Elkins says Tribes seek assistance from the FBI, which has long been criticized by Tribal leaders for failing to thoroughly investigate serious crimes against Indigenous peoples and inaccurate or non-existent documentation.

Elkins says Tribal members who are victims of crime have consistently been misidentified as white or Caucasian, which creates challenges for their Tribes when trying to locate them.

“When people are misidentified in the system, Tribes are not even aware of where they are, which means they can’t even reach out and help them,” she says. “In the last eight months, I’ve discovered the extent of the problems we have working with state and local municipalities to get that data corrected.”

“Our Chief of Police went to our neighboring municipalities to actually sit down and go through records to see where our people were misidentified.”

Last year, National Congress of American Indians President Mark Macarro, chairman of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs that there is so much need relating to public safety and justice in Indian Country, he did not know where to start. He called the situation an acute crisis that has been going on for decades. He blames the crisis on inadequate funding.

Macarro cited the federal standard for officers as 2.4 per 1000 people. The Oglala Sioux Tribe on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota has 0.6 officers per 1000 people.

“There’s 56 million acres in Indian Country, and given that there are a handful of officers on patrol and every call for service — Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons and other serious crimes, such as fentanyl and those committed by cartels — every call for service has an extended response time. It’s unacceptable. Every non-Native in any community in the United States wouldn’t accept what’s happening in Indian Country, and something needs to be done about that,” Macarro said.

Robin Elkins is the Vice-Chairperson of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi Tribal Council.

In April, the U.S. Justice Department announced that it will surge FBI assets across the country to address unresolved violent crimes in Indian Country, including crimes relating to missing and murdered indigenous persons. This surge is part of Operation Not Forgotten, which was established by Executive Order during President Trump’s first administration.

“FBI will send 60 personnel, rotating in 90-day temporary duty assignments over a six-month period. This operation is the longest and most intense national deployment of FBI resources to address Indian Country crime to date,” according to a Justice Department statement.

FBI personnel will be assisted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs Missing and Murdered Unit.

“Crime rates in American Indian and Alaska Native communities are unacceptably high,” said Attorney General Pamela Bondi. “By surging FBI resources and collaborating closely with U.S. Attorneys and Tribal law enforcement to prosecute cases, the Department of Justice will help deliver the accountability that these communities deserve.”

Elkins says this doubling down by the FBI is long overdue and is likely of little consolation to Tribal members who continue to struggle with the word “unsolved” as it relates to the cases of murdered or missing relatives and friends.

They are her reasons to march and speak out.

“We need to start working on legislation and holding people accountable,” she says.

“We need to keep working on it through our courts if it goes outside of what we can do as a Tribe. We need to keep talking about this until we’re blue in the face and then talk some more.”