Farmers age, demand for local food up: Do we have a problem?

Why wait for a crisis in getting food to those who need it if something to avert that outcome can be done? A group of citizens recently traveled to the Michigan Good Food Summit in Michigan's capital to learn about what's ahead. Donna McClurkan was among them and has this report.

Farmin’ ain’t easy – no it ain’t easy. — “Farmer’s Anthem” by rapper Lucas DiGia, a.k.a. Homegrown

Who will grow our food?

The question is haunting in light of this statistic: the average age of Michigan’s farmers is approaching 57 years. With retirement looming and many farmers with no solid succession plans, the fate of nearly half-a-million acres of productive farmland across our state is uncertain. Nationally, the numbers are sobering as well. According to the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, a division of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), an estimated 70 percent of U.S. farmland will change hands in the next 20 years. Most farms and ranches in the U.S. are family owned; many of these operations do not have skilled and willing heirs to assume farm management.

Rapper Lucas is right — farming isn’t easy. Weather variability, market volatility, pests, demanding physical labor and staggering capital requirements such as land and equipment make farming a business fraught with uncertainty and risk. Gone are the days when the farm was passed on to heirs. Today, career options are seemingly endless and fewer children choose the family farm.

Against the backdrop of a decreasing supply of farms and farmers, consumer demand for local food is skyrocketing. The number of farmers markets in Michigan has grown from 90 in 2001 to more than 290 today. Another sign of rising demand — the Michigan Farmers Market Association reports the number of markets participating in federally funded food stamp programs (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) went from 3 to 103 over the past six years. With a heightened awareness of the need for better nutrition, more schools, hospitals and prisons now incorporate local food purchasing directives into their strategic plans, further contributing to increased demand.

In Southwest Michigan, my little corner of the state, there is evidence that demand far exceeds supply for locally-grown fruits, vegetables, minimally processed prepared foods, artisanal cheese and pastured meat products. The resulting economic growth — and enhanced health of our citizens — benefits all of us. But the question remains, who will grow the food to meet this rising demand?

It turns out this question is top of mind for Wayland farmers Rose and Bill Scobey. The Scobeys — famous in Kalamazoo for their sweet corn, string bean varieties and wonderfully creative displays of bountiful market produce — have owned their 79 acre vegetable, U-pick and flower farm since 1975.

During my recent visit to their vendor table at the Kalamazoo Farmers Market, Rose shares her concerns about succession planning for their farm. As with many families, their two children chose off-farm careers. Bill and Rose have been trying for six years — “starting when arthritis set in” — to find a suitable family “with the right work ethic” to assume operations while they are still able to provide training and mentoring.

I wait patiently while Rose tends to her loyal customers: Steve, who stops by to say he’ll be back the first week in August to load up on sweet corn for a family gathering in North Carolina; a woman who gets a first taste of unexpectedly sweet sweet peas (“I didn’t know the pods are edible!”) and Kate Bultema, one of the Scobey’s 128 CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) subscribers, there to pick up her share of produce. The flow of shoppers slows. Rose reflects on growing up at the market at this same vendor spot first rented by her parents in 1947. And Bill says farming as a way of life is hard for many people to understand. “It’s really hard work, and we’ll never be rich, but the compliments … the people who appreciate our food … thousands of them over the years, keep me going.”

The scope of these dual challenges — the impending loss of farms and farmers within the context of rising demand for local food — crystallized for me during the Michigan Good Food Summit in Lansing on June 14. The Summit was the second in a series of working sessions to involve a broad and diverse range of people in a state-wide initiative to advance a re-imagined food system, the vision and goals for which are outlined in the Michigan Good Food Charter. Since its publication in 2010, more than 250 groups and individuals have signed the Charter’s resolution of support, affirming their belief in a food system that is healthy, green, fair and affordable. The Michigan Good Food Charter serves as a state-wide road map that offers strategies for transforming our food system.

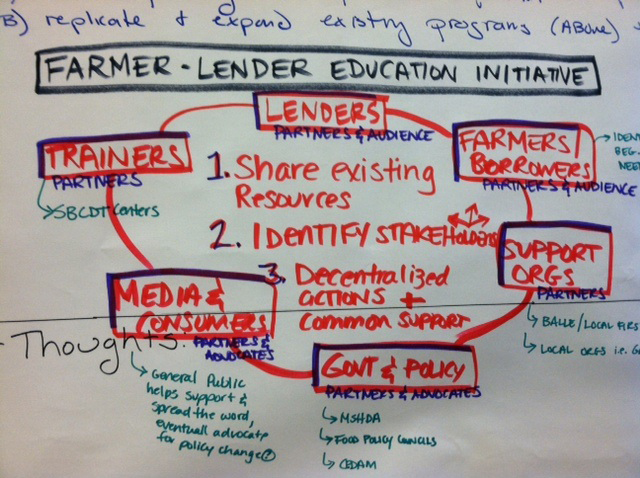

Leaders from the Center for Regional Food Systems at Michigan State University (MSU) facilitated a summit strategy session called “Building New and Beginning Farmer Capacity,” in which approximately 45 of us were given the task of creating an action plan to expand access to financing, education, land and other resources needed to support new and beginning farmers in Michigan. The energy in the room was palpable; in a very short time we agreed to divide and conquer. Half of us focused on ways to connect lenders and new farmers. The other 20 or so brainstormed ways to generate matches for mentor farmers and available land with beginning farmers. A subset of each group plans to continue this work and report on successes at the Summit to take place in 2014.

More than 350 people came to the Good Food Summit in Lansing to continue work started two years ago. We left with a new appreciation for the accomplishments and successes taking place across the state and re-energized – thanks in part to rousing rap songs – for the work that lies ahead.

In his high energy tribute, Farmer’s Anthem, rapper Lucas DiGia reveals the transformational power of his “step up to farmin.'” May it be so for all of us in Michigan!

Outlets for Donna McClurkan’s food-related passions include serving as Board member and Policy Committee co-chair for the Michigan Farmers Market Association (MIFMA), co-moderating the EatLocalSWMich Yahoo Group, and crafting occasional articles on local food initiatives. Her family is starting a farm in Bangor.

Photos by Donna McClurkan

Rose Scobey and Kate Bultema at the Kalamazoo Farmers Market.

Those attending the Michigan Good Food Summit brainstormed ways to get lenders and farmers together.