Women break down the barriers in the world of ink

The tattoo industry brings in revenues of at least $2.3 billion each year. An estimated 23 percent of women have tattoos. And some of them are seeking out female tattoo artists.

Tattooing has historically been known as a “man’s world.” In many ways today, it arguably still is. But, as the industry explodes, and more genders seek out tattoos, the demand for women artists is increasing. And those women are making waves in the industry across the globe, including right here in Southwest Michigan.

Though, often, it’s not easy.

“I compare it to when I used to skateboard on half pipes and at skate parks,” Beck McGinnis says about making it as a woman artist in the tattoo industry. “The minute a male sees a female ‘attempting’ to master a skill in ‘their world,’ you’re met with, at minimum, subtle and sometimes overt prejudices. It’s incredibly competitive. A pissing contest for fame and ego.”

McGinnis, a small-time homesteader living on the outskirts of Kalamazoo with her partner and his 4-year-old daughter, has been tattooing for five years. She began her career in tattoo artistry shortly after completing a fine arts degree in illustration, when she was approached with an apprenticeship opportunity. She ended that apprenticeship after a year because of sexual harassment she says she endured. She took five years off to save up enough money to complete her apprenticeship under a woman artist in Indiana. Shortly after completing that apprenticeship, she moved to Kalamazoo. The barriers around her gender have been so intense that she uses the nickname, “Eddie,” so that her clients have an opportunity attain a small amount of trust in her competency before meeting face-to-face when her gender is revealed.

“I’ve literally had walk-in clients ask, ‘can a woman even tattoo?’ after I had been presented as the artist they would be working with,” McGinnis says. Her male co-workers try to diffuse the situation by touting her abilities and showing the artwork she had done on them, and offers self-deprecating jokes as a way to ease the tension and just get to doing the tattoo. McGinnis says she feels a strong push to work harder to prove herself, and says she’s frequently compared to other female artists or “tokenized” by well-intentioned clients “seeking to give women artists a chance.”

No one was into helping ‘the new girl’

Raven Wynd of Otsego has been tattooing for the past 24 years. She gives a firm nod to gender-based obstacles in an industry that is dominated by men. “When I started in 1991, there weren’t many tattoo artists around — and maybe 5 to 10 percent were women,” she says. “No one was into helping the new girl. I was met with quite cold shoulders.” In the beginning, she ran into annoying things like people coming into her self-owned shop and asking for, “the guy that runs the place.” She says, “Women aren’t taken as seriously,” and points to societal pressures for women to conform to traditional roles, which don’t “leave much time to perfect the art form.”

Wynd grew up with a father in the military and a mother who was an artist. You could say her passion for artwork was inherited. Her mom’s primary medium was sculpture, and Wynd, in addition to her primary art form of tattoo artistry, has established herself as a 3D artist, as well, competing in — and winning – local art competitions. You can find one of her sculptures in the park just down the street from her downtown Otsego tattoo studio.

Despite the obstacles women artists face, Wynd says there’s plenty of work and that if you can draw, people will be attracted to you. But, she says, “you also have to be willing to listen, and to set aside your ego.” Wynd is a self-described competitive person. She says, though, that while the industry is competitive, her competition isn’t against other artists, it’s against herself. “What I compete with is the ideal…. I’m in competition against complacency. I don’t want to settle for just cranking out photo copies of other people’s crap. I want to suit the body art to the person.”

The right place at the right time

Kendra Chudy relates to a commitment to high-quality work and increasing one’s skill and form. Chudy began her career as a tattoo artist under an apprenticeship with Wynd in 2002. She now tattoos out of her self-owned shop in Richland. She says she came into the business by “being in the right place at the right time.” That right place happened to be in Wynd’s shop, where she accompanied a friend for a tattoo. Chudy had recently completed her fine arts and graphic design degrees and, after seeing Wynd’s work, she asked her about teaching her skills, to which Wynd replied that she’d need to start as an apprentice. “I brought her my portfolio developed from my college classes and it began there.”

Chudy worked with Wynd for 11 years before opening her own shop in Richland. Chudy is aware of the “luxury” she had in her training — an apprenticeship with an established woman artist, and income support from her partner so that she didn’t have to worry about an unpaid apprenticeship. And she had a lot to offer, too. While she didn’t know much about tattooing, she did know how to draw and design. And she was motivated, committed, and willing to go above and beyond what was expected of her.

Today, Chudy’s clientele base is 65 to 70 percent women. While Chudy is adamant about her work being defined by her art and not her gender, she says, “Often women look for other women as artists. They tend to be more comfortable with a woman tattoo artist because we speak the same language.”

Women supporting women

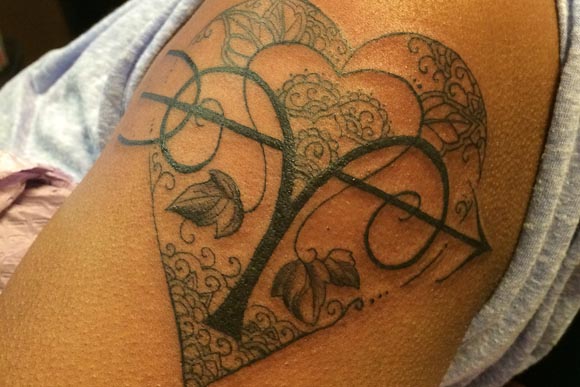

For Heather Butts of Battle Creek, her last tattoo was absolutely about finding comfort in someone who spoke the same language. But, for her, it was also a safety issue. When the 28-year-old, newly single mother of three, was going through her divorce, she felt compelled to mark her body with a floral piece on her shoulder. “It was to signify the strength of nature, my beautiful body, and the bravery I was going to need to move forward with my life,” she says.

The first artist Butts worked with, “seemed to only care about the lines.” He chastised her for being too “emotional,” did the work fast and sloppy, and in the end, Butts described the result as horrible in looks and effect. “When he finished, I felt so violated.” She said she knew it needed to heal and then be fixed. She determined that “no other man would ever come near (her) with ink and needle.” That’s when she sought out a female artist. She traveled to the east side of the state, on a recommendation from her sister. “When I sat down for the consult, I was in tears. She, too, was teary-eyed and kept running her fingers over the shoddy work, apologizing for how badly it was scarred.”

When Butts talks about her experience with the woman artist, it sounds more like a rite of passage than merely of producing an end product. “I realized just how important it was for me to feel how painful it was. How intense it was to work over that tortured skin. She was patient and kind. She wasn’t trying to make me be tough, or feel a certain way. She just allowed me to experience the tattoo, the process of healing from the first time, and go into the sensation of transformation. We laughed, we talked. It was natural and easy.”

For many people with tattoos, the ink is much more than just body art – their bodies become a canvas for the larger narrative of their life story. “Adrenaline junkie,” Yelena Kleshchik recently returned to Kalamazoo after three years exploring hundreds of thousands of miles across 48 states and eight countries. She says her most passionate connections are to nature and human relationships, and all of her (presently five) tattoos are inspired by nature, travel, and people.

Kleshchik didn’t always seek out women artists for her work, but for her last tattoo, an outline of the Great Lakes on her forearm, she did. Coming from a family that placed an emphasis on rigid gender roles, Kleshchik was constantly reminded that “women are meant to be in the home cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the children.” Her family subscribed to the male dominant head-of-household dogma, and these concepts always felt unsettling to her. “When, in middle school, my mother enrolled me in ballet classes, I decided to join the football team instead.” Kleshchik says that she found it increasingly difficult to find support, not only from her family, but from a society, that while evolving, is still entrenched in ideas of what a woman “should be.”

“I find great inspiration in women that defy societal norms, not to prove a point, but to follow their heart’s desire. I choose to surround myself with these types of women and a tattoo artist was no exception. If someone was going to mark my body permanently, it was going to be a badass female doing what she is passionate about in a society that deems it ‘unacceptable.’ For me, there was no other option,” Kleshchik says. While she knows that there are incredible artists of all genders, Kleshchik notes, “there’s a humbleness that comes from paving a successful path in a male-dominated culture.”

Popularizing tattoo culture

TLC’s popular show, “Ink,” has increased exposure not only for tattoo culture, but for women artists in the industry because of one of their prominent featured artists, Kat Von D. Wynd says she has a love/hate relationship with Kat. “She’s young and beautiful and makes $5 million a year and barely had to work. That’s why I ‘hate’ her. But she brought tattoos and the stories behind them into your living room. She made them a story — not just this weird thing that people do.”

McGinnis agrees that the TV series, and Kat’s prominence is increasing exposure, but feels her lend to helping women as artists is small. She says, “The show Ink uses her sex appeal (which perpetuates beauty norms) to market the show…. I feel privileged to fit certain beauty standards when someone, who is questioning my skills, meets me for the first time. I can feel (in the air almost!) a higher trust in me from clients as opposed to the lack of trust of a woman I worked with who was less conventionally attractive. It’s taboo but we all know it exists. Kat is presenting the idea that women are skilled but it helps to be sexy. We are a long way from seeing the face of women with unconventional beauty be respected in the industry.” When McGinnis watches the show, she sees Kat being portrayed more like a “pinup girl playing along with the ” boys” in the boy’s world.” She says she’d feel more empowered by Kat if she chose to make waves in the industry.

Humility, commitment, and practice

McGinnis recalls the first time she set a tattoo needle to … a grapefruit. It was there that she learned how hard it was to regulate the depth of the needle. Eventually she did her first tattoo on a human – her best friend. She says it was “horrible,” and calls it a “humbling experience.” She says, “as time progresses, I still face each tattoo I do with a sense of humility. I learn every time I do a piece.”

The theme from all of the artists is a commitment to their craft. “Draw. Draw three hours a day. Draw other people’s ideas,” says Wynd when asked about advice for other women considering the business. Chudy agrees. “Most reputable artists want artists — we want someone who can draw, is artistically trained, and has a good eye for design and layout, and maybe even a distinctive style of their own. That should be your focus,” she says.

McGinnis can’t emphasize enough the importance of carefully selecting a mentor, and says, “there is a power dynamic established in an apprenticeship scenario.” For her, it meant removing the already existing male to female social hierarchy and working with a woman. She suggests other women seeking to get into the industry do the same.

“Don’t lose yourself to the callousness that comes from ego. I find women artists hold space for challenging the macho atmosphere often created in shops and can be more welcoming to marginalized communities,” McGinnis says, “It’s worth it to fight for that kind of change.”

You can find Beck McGinnis at Kitten Flower Boutique in downtown Kalamazoo, Raven Wynd at Tattoos by Raven in downtown Otsego, and Kendra Chudy at Inked by Kendra in Richland.

Kathi Valeii is a writer, speaker, and activist living in Kalamazoo. She writes about gender-based oppression and full spectrum reproductive rights at her blog, birthanarchy.com.