Voices of Youth: How teens can help friends in crisis

A Voices of Youth writer delves into how teens can best help comfort friends in crisis. Experts stress the importance of sincere support, open dialogue, and knowing when to guide someone toward professionals.

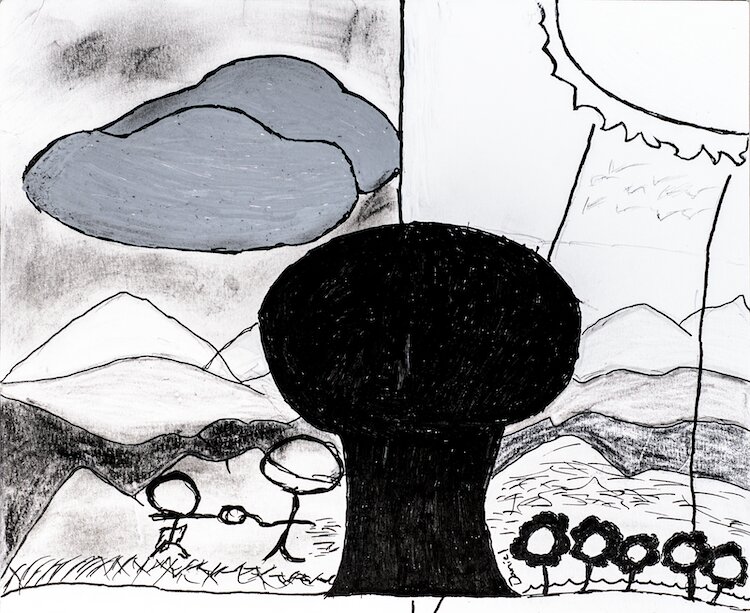

Editor’s Note: This story was reported by Jack Reilly, and the accompanying artwork was created by Daniel Kibezi as part of the Spring 2025 Kalamazoo Voices of Youth Program. The program is a collaboration between Southwest Michigan Second Wave and KYD Network in partnership with the YMCA of Greater Kalamazoo, funded by the Stryker Johnston Foundation. The Voices of Youth Program is led by Earlene McMichael. VOY mentors were Al Jones (writing) and Taylor Scamehorn (art).

KALAMAZOO, Mich. – Kayla Ricardo, a freshman at Loy Norrix High School, laughs awkwardly. Beside her is a friend who has a dear family member with a fatal disease. Ricardo doesn’t know what to say.

Whenever the friend starts to talk about the relative, Ricardo tries to change the subject. At age 15, she struggles with how to comfort her friend. She’s also not sure if her friend really wants to talk about it.

On one occasion at school, she was able to avoid the difficult conversation because an event they were at started, allowing her to dodge the whole thing for a bit longer.

While juggling assignments, homework, sports, jobs and other things, teenagers watch their friends go through many types of crises. It’s difficult to know just what to say and what to offer when they want to help, but they’re both young and sometimes nobody knows what to say.

“Be transparent and be supportive,” suggests Vincent Hodge, Ph.D., a certified school psychologist at Gull Lake Community Schools. “It’s OK to tell your friend, ‘I’m kind of worried. I’m kind of concerned.’ ”

Your chances of helping that friend work out their issues or get professional counseling are better if you have a good connection with them, he says. “They know you’re sincere.”

Friends are important

A crisis is different from one person to another and can range from a failing grade to an abusive relationship. In any situation, it’s important to stay by a friend’s side, professionals say. Online therapy service Synergy eTherapy recommends saying phrases like, “You’re not alone,” “I’m here with you” and “It’s alright to feel this way.” That lets the friend know that their feelings are valid and that they’re not going to have to work through it by themselves.

Hodge says that even if a person rejects help from you at the start, and it’s tough, it’s important to let them know: “You mean a lot to me’” and “Let me know what you need. I’m happy to go with you if you need help.”

On the other hand, counselors with Synergy eTherapy say there are harmful things that you should not say. For example, stay away from telling them things like: “Everything happens for a reason” or “Others have it worse.” They don’t need an explanation or a dismissal of how they feel.

According to The Mental State of the World in 2022, Friendships and Mental Wellbeing by Sapien Labs, those who lack friends to open up to are 3.5 times more distressed than people with friends to lean on. More than 400,000 people from 64 countries were surveyed.

Professional help may be needed

The Mental Health Foundation has eight steps to a healthy conversation around a crisis. The Scotland-based advocacy organization promotes emotional wellness in the United Kingdom. The group says the first step in having a sensitive conversation is to set aside time in a private space to let a person open up about their problem. A few other steps include:

- Avoid assuming or diagnosing their feelings. Telling them that you think they seem sad or that they might have PTSD won’t comfort them.

- After they’ve opened up, try to find some coping strategies that cater to them. This might be cooking, drawing, reading, writing, and a plethora of other things.

- Don’t try to do it all. When someone is in a serious or potentially dangerous situation, you cannot fix it all. Try to refer them to a professional for help.

“In those instances, I would say something like, ‘Hey, I don’t know what to say, but I know someone who does,’ ” says Frank Lewis, a therapist and interim suicide prevention manager at Gryphon Place, a resource center for people in crisis and conflict in Kalamazoo.

While it’s encouraging that you want to comfort your friend, it’s alright if you don’t know how. Instead, Lewis says, direct them to a trusted adult who can help.

“We kind of meet people where they are when it comes to their crisis,” says Lewis, who is also head of the Gatekeeper program, an in-school training program at Gryphon Place that spends four days (usually as part of a health class) teaching area high school students how to spot classmates in crisis and what to do to help them.

“Sometimes, it’s something that is an immediate thing,” he says of people’s needs. “And sometimes, it’s something that is kind of building up to where action needs to be taken. Or it could be in the aftermath — after something has actually happened to someone.”

In the four years he has been involved with the Gatekeeper program, he says he has seen students who are actively considering suicide and some who are in a questioning stage.

“It’s not that they necessarily want to die,” he says, “but they also don’t feel quite like they want to live at this point, too.”

He says both are situations where you want to get help for that individual, “because. clearly, they are reaching out.”

“When someone talks to you about their feelings, it’s a pretty good indicator that there’s some fight left in this person,” Lewis says. “This person still wants to stick around. They want to live still. They just might not know exactly what that means for them at that point. They are not sure how to cope with what’s going on around them.”

In those situations, Lewis stresses the importance of staying calm. It helps the other person feel safer and more comfortable, and to believe he or she can talk to you about what’s going on.

Lend a listening ear

Sage Lee, a sophomore at Loy Norrix High School, believes showing signs of being a good listener is important when offering comfort.

“I think just reassuring me that I have people in my life that I can go to, reminding me of my resources, and just being a person, I can sit with (are things that would help),” Lee says. “I think the most overlooked comfort is someone who can sit with you – someone who just nods and lets you talk to them.”

Other recommendations from Hodge and Lewis: If you notice a shift in your friend’s behavior, confront it as soon as possible; don’t let the person retreat from the conversation. It’s imperative to tackle the problem immediately. You don’t know if a day more could cost his or her life.

If you’re worried about someone harming themselves, Lewis recommends asking directly if that person is thinking about suicide. That alleviates any chance of a misconception. And he says you should interpret any answer that is not a clear “no” as a “yes.”

He says a lot of people are worried that using the word “suicide” will put that notion in the person’s head. But “what it is actually going to do is make someone feel more comfortable about sharing how they feel,” Lewis says. “It lets a person know that you understand what they may be feeling at a point like that — and that you have the intention of helping them. And that you may have an idea of how to do that.”

For people who are dealing with significant stressors less than a crisis, Lewis says you may ask: “How have you been coping with all the stress? I’m noticing that you’re very overwhelmed lately. I’ve noticed that you have … (make note of the things that are going on in their lives) … And you can ask them, ‘How have you been coping with all the stress? What have you been doing to manage your stress levels? What makes you feel better?’ ”

You can listen to learn whether the person is dealing with it in a healthy or unhealthy way, he says. Or maybe the individual doesn’t know what to do. After that, you can loop in a responsible adult — perhaps someone you trust and your friend trusts — to help connect him or her to relevant resources.

“A student can do the same thing, too, with things like our National Suicide and Crisis Line (988) or the local number (381-HELP),” Lewis says. “Those are resources that are always available for students. And it’s not just for suicide prevention either. … It’s for crisis, which is different for many people.”

Jack Reilly is a freshman at Loy Norrix High School in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He enjoys writing poetry, drawing, and occasionally photography. He hopes to major in psychology at Western Michigan University and become a psychologist or therapist who works with children and teens.

Daniel Kibezi

Artist Statement: Hello, I’m Daniel Kibez. My artwork explores the journey from adversity to healing, emphasizing the transformative power of peer support. The composition is divided into contrasting landscapes:

- Left Side: Dark mountains under cloudy skies, with weeds symbolizing struggle.

- Right Side: A radiant sun casts beams onto blooming flowers and checkmarks, representing hope and progress.

Central to the piece is a figure guiding another toward the light, highlighting the significance of companionship in overcoming challenges. I utilized Posca pens and colored pencils to achieve vibrant contrasts and intricate details, enhancing the visual depth of the work. By juxtaposing these elements, I aim to evoke an emotional response that encourages viewers to reflect on their own experiences and the importance of supporting others. This piece serves as a visual metaphor for the resilience found in shared journeys toward healing.